Svetlana Swinimer’s Unveiling the Goddess taught us lots about Slavic culture as well as contemporary womanhood

Svetlana Swinimer’s art installation, Unveiling the Goddess, introduced visitors to the many layers of Slavic goddess, Makosh. Showcased at Ottawa’s Gallery 101 from Oct. 9 to Nov. 7, this two-story installation transported visitors into Swinimer’s interpretation of ancient Slavic society.

As the goddess of water, textiles, harvest, and birth, Makosh, according to the installation, means “Mother of Destiny; giver and taker of life.” Despite Swinimer’s native connection to Indo-European culture, only recently did she learn about Makosh. In her view, Makosh is a forgotten deity, and through her art, she’s aimed to rekindle a relationship with her.

A mathematician by trade, Swinimer is also interested in the cosmos, and has equal interest in artistic expression.

“I am not a painter and I am not a sculptor. I am an artist. I work with my hands and my artistry takes various forms,” she said. She explained she chooses her artistic medium based on the ideas she wants to express.

Swinimer entwines the deity with symbols of nature in her artistic depiction of Makosh and does not give Makosh realistic human features. For example, plots of land stand in for her body, and in each of the goddess’s hands, she holds a bird and a flower.

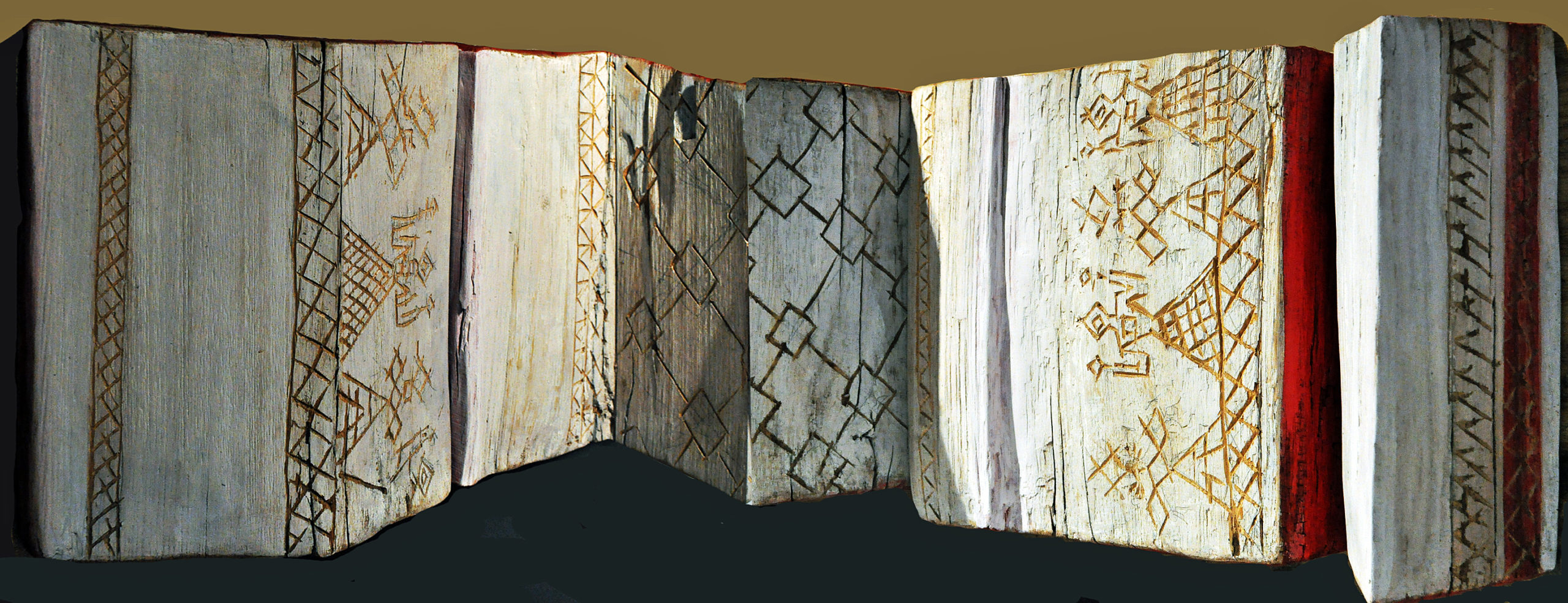

Makosh, in the installation, is imperfectly cut from blocks of wood, painted onto large rice bags and burlap sacks, and is hand-pressed onto rice paper. So to ‘unveil’ the goddess, Swinimer shows the various ways that Makosh embodies the natural world.

Swinimer explained that “Makosh was kept alive for centuries through needlework on domestic textiles.” She was called on to protect newborns and to ensure the maintenance of peaceful family relations. So to understand Makosh, we must not turn her into an unreachable philosophical abstraction. Makosh is a comforting presence who exists all around us. Swinimer urged the importance of ‘feeling’— rather than analyzing — one’s way through the installation.

Though no longer widely celebrated by Indo-Europeans due to the many years in which Christian groups suppressed the Slavic religion, Makosh lives on in the form of a new deity: the Virgin Mary.

In the Slavic-Christian tradition, Mary evolved to adopt Makosh-like traits and Swinimer says that Makosh is something of a universal constant. Many cultures emphasize the protection of nature and womanhood. Svetlana says that the Celtic goddess, Brigit and the Japanese goddess, Amaterasu are examples of goddesses who “know the fate of all men” — just like Makosh.

One of the only art pieces in Swinimer’s installation that does not represent Makosh is a five-metre-tall painting which depicts the oldest known sculpture in the world: Shigir. Everywhere you turn in this installation, Shigir is in view, and on the second floor there is a large window where you can meet Shigir face-to-face.

Swinimer used recycled material to create the pieces in Unveiling the Goddess. She used a rice bag instead of a canvas, as well as old blocks of wood for her sculptures. This emphasized Makosh’s connection to raw elements. Makosh is of nature. And when I stepped into this installation, I remembered that I too am of nature. This is what Swinimer’s installation reminds us: Makosh, no matter what we call her, is already woven into our lives, because we rely on nature to survive.