U of O student changes career, exhibits painting in human rights show

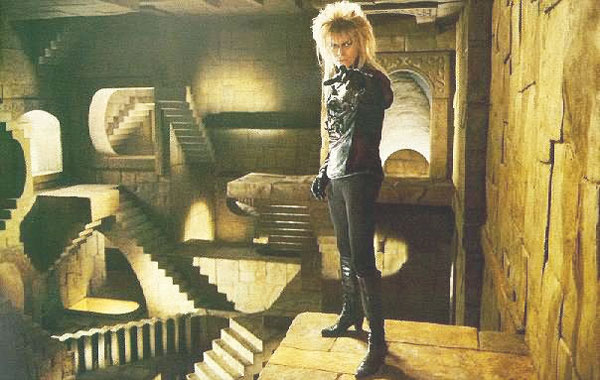

Photo by Tina Wallace

Lilly Koltun has three degrees in art history, including a doctorate, and a long career in museum curating, but she wasn’t an artist until the government started making budget cuts in the arts.

From Oct. 23 to Nov. 22, Koltun’s painting, entitled Polish Demonstrators, is showing in the Human Rights Research and Education Centre’s second human rights themed art exhibit. Held in Room 550 in Fauteux Hall, the exhibit’s theme is RED: Respect, Equality, and Dignity.

When the government stopped supporting the initiative funding the Portrait Gallery of Canada and Koltun’s job as the director of the gallery was eliminated, she decided to use it as an opportunity to try something new.

“I discovered after having a whole career—35 to 40 years—thinking I knew something about art,” she says. “I discovered that making it is a totally different thing and I didn’t really know anything about it at all.”

Not having a collection of artwork to choose from, she created pieces specifically for her portfolio in order to apply to the University of Ottawa’s visual arts undergraduate program. She was delighted to be accepted and is now in her fourth year. She loves the program and considers the campus to be emblematic of Canada as a country.

Koltun’s piece in the human rights exhibit is based on a newspaper photo depicting Polish demonstrators outside a 2012 trial of former communist officials in Warsaw. The demonstrators are holding photos of people killed under communist martial law.

“The concept of justice is what underlies all of our lives,” she says. “As someone who is not at all sure that there is an afterlife and that there is a just God who will give everyone their just deserts, to me it’s extremely important that in our present lives, we are just, that we do the right thing, and that people who are involved in heinous crimes are brought to account for that.”

“The concept of justice is what underlies all of our lives,” she says. “As someone who is not at all sure that there is an afterlife and that there is a just God who will give everyone their just deserts, to me it’s extremely important that in our present lives, we are just, that we do the right thing, and that people who are involved in heinous crimes are brought to account for that.”

When Koltun saw the photo, she was impressed with the ordinary people who have outlived an oppressive regime and still hope for justice even when it remains uncertain whether it will be served.

“It was important to acknowledge them and their memory and their willingness to take a stand with respect to their own ethics,” she says. “The only way I could do it—the way that it seemed to me I could contribute the best—would be to do a work of art.”

While she says that some may see the role of art as strictly aesthetic, she believes it is much more formidable. She relates the experience of seeing an artist wearing a button in the midst of a controversy over censorship.

“The button said, ‘Fear no art,’” she says. “I looked at it and I thought, ‘No, no, no.’ People who censor you know very well that you should fear art, because art is very powerful. Art really can make people change their minds.”

In addition to Polish Demonstrators, a show of Koltun’s work will open at Gallery 115 on Oct. 31.