After a couple disappointing years, online based education is poised to make a comeback. But what form will it take and what will the consequences be for the U of O and Canadian universities at large?

It wasn’t that long ago when it seemed like the concept of e-learning was going to shake the traditional post-secondary education system down to its very core.

If you go back a couple years, you’ll find article after article heralding the arrival of purely Internet-based learning and how physical university lecture halls are on the cusp of being obsolete.

This kind of rhetoric got a lot of play in the media, as it tapped into people’s understandable frustrations with higher education, like crippling student debt and the rising cost of tuition.

The New York Times even went so far as to dub 2012 “The Year of the MOOC”, referring to massive open online courses (MOOC) and their ability to provide access to free, post-secondary level course material to anyone with a decent Internet connection.

However, fast forward to the present day and most students could tell you that the concept of online-only courses didn’t really live up to the disruptive, firebrand quality that was once prophesied.

Due to a high level of dropouts, low completion rates, and poor implementation strategies overall, the so-called MOOC “revolution” was largely seen as a dud. And with student enrollment at universities still being steady, many online educators are now being forced to re-think their strategies entirely.

So, with this in mind, what does e-learning look like at the University of Ottawa in 2016, and how could it change face of campuses across the country?

Hindsight is 2020

Despite the previously mentioned shortcomings, the U of O hasn’t wavered in their support of e-learning, and has already taken steps to redeem the reputation of online courses in the eyes of the public.

To spearhead this initiative, a group of local U of O professors and academics released a report on e-learning back in March of 2013. The recommendations contained in this document were quickly adopted by the university administration and merged into their much touted Destination 2020 strategy.

One of these recommendations involved developing a single MOOC as a pilot project, in the hopes of ironing out some of the wrinkles that have plagued previous iterations of this teaching method.

This redemptive quality is definitely at the centre of Nancy Vézina’s mind, since—being the educational programs manager for the Teaching and Learning Support Service (TLSS)—she is one of the main project leads behind the development of this online-only, French language biology course that is set to be released sometime in the spring.

“There’s a few (courses) I looked at a few years ago. It was basically just a recording of a prof doing a lecture in class and pushing it into a MOOC format,” she said, describing some of the design flaws that caused so many previous MOOC projects to fail.

“So I think we’ve tried to do something a bit different. We’ve used a lot of visuals, a lot of simulations of information, a lot of interactive activities so that it’s not just watching and listening to someone.”

However, one of the biggest takeaways from the report is its ringing endorsement of blended courses, a type of learning that takes the best elements of online courses and face-to-face teaching and combines them together.

Richard Pinet—head of the U of O Centre for e-Learning and one of the co-authors of this report—states that these hybrid courses can be dished out in a number of different ways. This includes a “flipped learning” permutation that asks students to absorb lecture material electronically beforehand, and to bring their ideas to class for discussion groups and different learning exercises.

“It’s really a change in philosophy,” said Pinet. “It’s shifting the responsibility of the prof standing at the front of the room telling students what they need to know or memorize for the exam, and making the learner the centre of their learning.”

The U of O is currently host to over 76 such online courses, a number that is only going to increase since the administration plans to transform 20 per cent of all its course material into this format by 2020.

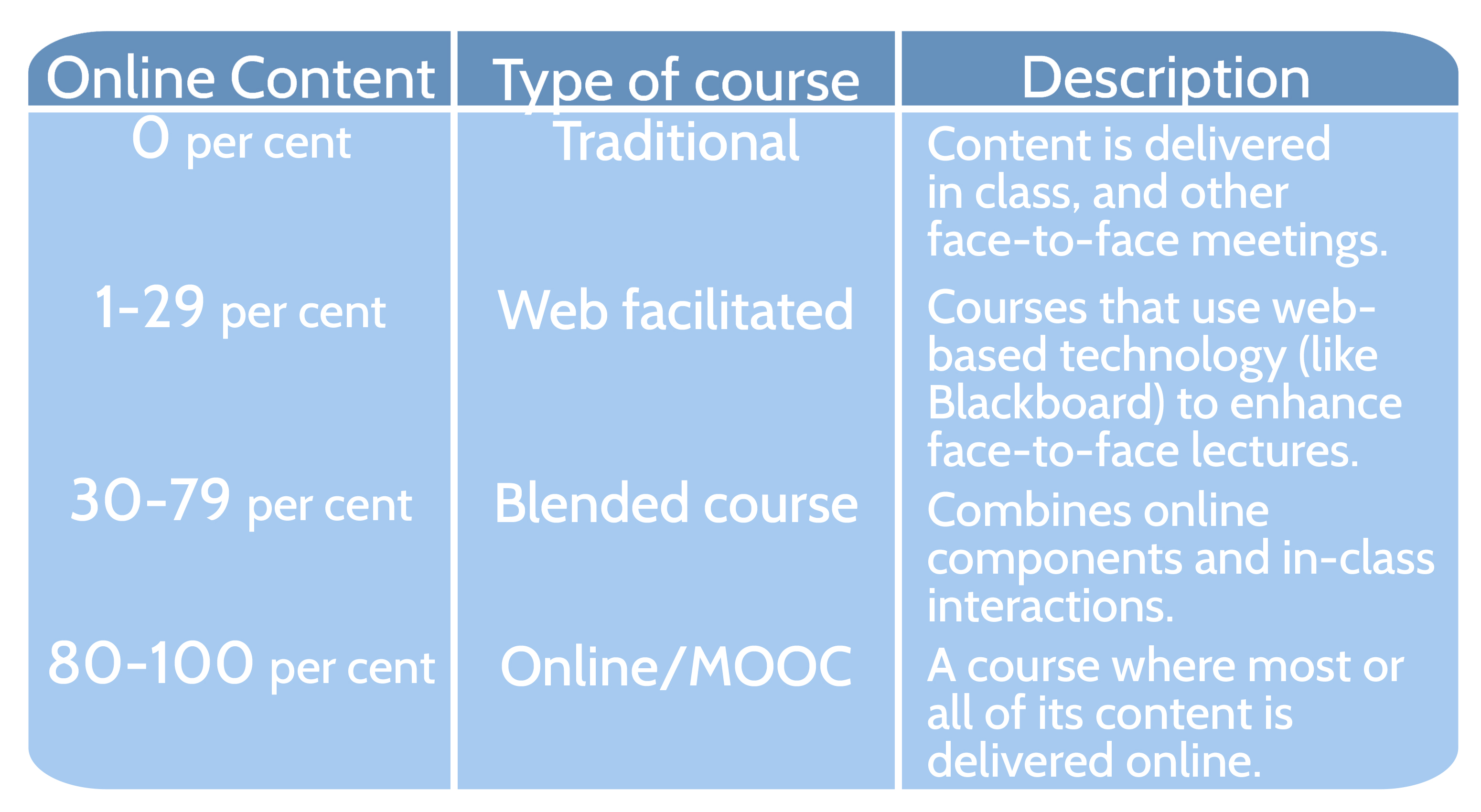

Course classifications

Graphic: Kim Wiens. Source: Blending In: The Extent and Promise of Blended Learning in the United States.

In the mind of Dr. Tony Bates—a venerated consultant who specializes in e-learning—this kind of policy puts the U of O ahead of other post-secondary institutions in terms of their commitment to creating a sustainable future for online learning.

“They have an institutional strategy. They have a well-supported department. They have programs in both French and English online. So yeah, I think it’s in the top third certainly.”

The teacher becomes the student

Even though studies show that blended courses result in better grades and increased student engagement overall, this form of learning is not without its potential downsides.

Some believe that this seismic shift in teaching styles will be too much to bear for certain professors and will, in turn, end up costing them their job or their shot at getting tenure.

Having taught blended and other online courses for almost a decade, professor Nicholas Ng-A-Fook of the U of O Faculty of Education is wary of these concerns. In his experience, it can take “three to four years to kind of get it where you want to in terms of the content and all the bells and whistles,” which may be too much of a learning curve for professors who are underpaid and severely overworked.

“If your tenure relies in part on your teaching scores through course evaluations, if face-to-face is working for you… you’re not going to change what you’re doing to jeopardize those teaching scores. ”

While Pinet is similarly sympathetic to the plight of downtrodden instructors, he believes that, with a little guidance, transferring over from a strictly face-to-face format to an (at least partly) online interface can actually improve their teaching skills.

“Generally speaking, profs who come to work with us end up leaving after they’ve created a course saying they’ve become better teachers as a result,” he said.

According to Pinet, converting pre-existing material into an online form forces profs out of their comfort zone and encourages them to re-evaluate their entire teaching method.

Bates believes that this this is an essential step in improving teaching methods overall, since, in his mind, universities currently put too much pressure on their professors to direct their attention outside of the classroom.

“What I think the big problem is: we don’t provide adequate training for faculty members,” he said. “Because they’re not being trained as teachers and educators. They’re being trained as researchers.”

This concern is made even more tangible based on the Liberal government’s new budget, which promises to allocate millions of dollars to bolster post-secondary research projects on campus.

Re-defining campus life

Although he is fully supportive of online learning, Ng-A-Fook still can’t help but raise concerns about how the growing popularity of e-learning will impact the social experience of university.

“The larger context of a teaching, learning community as a whole goes well beyond the classroom in terms of all the additional things that we do,” he said, alluding to students participating in campus clubs, varsity sports, and various other university organized social events.

“I would hope that if you’re paying your tuition, it (includes) access to all the services that the university provides, including your professors.”

Pinet concedes that many of these issues are well-founded, and that the process of transitioning over to more of an online-focused education model can be an isolating experience for students (especially newcomers).

However, he believes that this feeling of loneliness can be alleviated if the professors in charge choose to utilize the right tools and modules, including discussion forums and regularly scheduled Skype sessions with students.

“I had a small class mind you, but still, I got about three quarters of my class coming routinely and we would have really good conversations and chats,” he said. “So there are ways of addressing that feeling of isolation and I do sympathize with it.”

Unfortunately, these teaching strategies don’t take into account the idea that as online education models become more and more prominent, the value of coming to campus may shrink.

According to the same e-learning report from 2013, if the U of O hits its expected goal of establishing 20 per cent blended courses by 2020, the number of extra classroom spaces could be cut down by 10 per cent.

While increased space for students is undoubtedly a good thing, this strategy also flies in the face of the U of O’s plans to expand the campus, having just built a brand new $70 million research facility (and with a new Learning Centre on its way in 2017).

To Bates, this means that the university administration will have to drastically re-think what role or function the physical campus will play in the future, especially if they still expect it to be a vibrant hub of student activity.

“So the challenge now is to say ‘What’s the role of the campus when students can do most of their stuff online?’ ‘Why should students get on the bus to go to campus?’

“Now if you’re going to have a billion dollar campus you better damn well find good uses for it, otherwise students will stop coming and they will do everything online.”

The student becomes the teacher

So yeah, e-learning doesn’t have quite the same “punk rock” appeal that is flaunted a couple years back. In fact, at the U of O anyway, it’s very much a part of the establishment.

According to Pinet, the e-Learning Centre is busier than ever, consulting with virtually every faculty in the hopes of living up to the administration’s vision of a future where online learning comprises at least one fifth of its courses.

And while this transitional period is sure to bring about some growing pains, Pinet believes that it is a necessary move, given how the distribution of information in the Internet age has now put the onus on students to become their own teachers.

“The nature of learning has radically changed, not because of online but in parallel to online and blended (learning), because there’s been a realization that student-centred learning is a better form of learning than simply the regurgitation of material that is spouted from the front of the podium.”

Whether or not the educators and school administrators behind this new cycle of blended courses, MOOCs, and other online education modules can learn from the mistakes of the past is still up for debate. However, Bates believes that moving forward with more online courses is the only realistic move they have, and that there is no going back.

“You can no longer go on teaching in the way that we used to in the 19th century. The world has changed and universities have to change with it.”