Emotional abuse from parental figures during childhood can have detrimental, long-lasting impacts

CW: This story contains accounts of emotional abuse.

I remember the feeling of being a ten-year-old. Like other kids my age, I stressed about making the hockey team, the clueless but oh-so-cute desk partner who I passed notes with, and whether I would get a good grade on my solar system model.

But these aren’t the things that stand out about my days pre-adulthood—these are the things I hold close when I remember that while growing up I contended with some things that no ten-year-old should.

I remember climbing onto countertops to put the dishes away hurriedly, worried that my dad would yet again fling labels like “lazy ass” my way. I remember being five minutes late after soccer practice, only to be met with disproportionate rage and accusations of disrespect, followed by threats to pull me out of the very sports that brought me so much joy. I remember cowering in my closet or under my covers as I heard the heavy footsteps coming down the hallway, with curse words I’d never heard before hitting the walls around me. The fear that one day he would eventually snap and kill me, or worse, my whole family, was always top of mind.

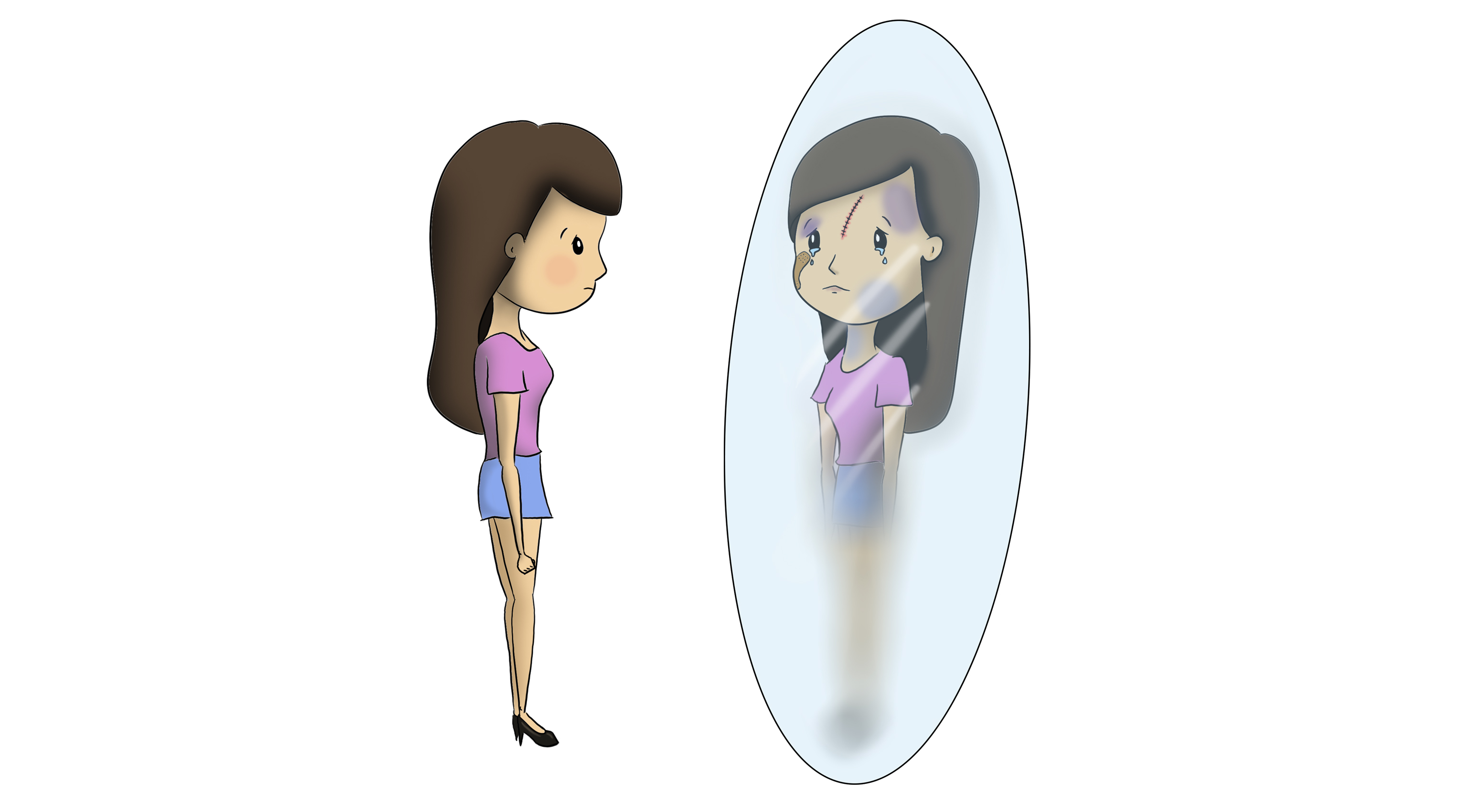

Most of all, I remember being convinced explicitly through words or implicitly through violent flashes of anger that my actions were always inherently bad, that my perceptions were inaccurate—that I was constantly doing something horribly wrong.

What other explanation could there be? If my father was this angry at me all the time, it had to be because something was terribly wrong with me. If he couldn’t even look at me with love, if he screamed louder as my tears grew faster, I must have been born with an irreparable defect.

When we talk about abuse, many of us will immediately conjure thoughts of bruises, blood, scratches, or worse.

This is obviously horrifying and detrimental in its own right, but the insidious thing about emotional abuse is that there is little to no physical evidence. You feel crazy, anxious, depressed, or worse, nearly all the time. And especially amid the hormone-heavy time of adolescence, it’s hard to even recognize what’s happening to you in the moment.

I started having panic attacks when I was 11, but I barely remember a time I didn’t have severe anxiety. Between walking on eggshells to appease my father, to being convinced I had to tell my mom I loved her every time we parted ways just in case it was the last time and checking the locks on the doors obsessively each night, my house was never synonymous with comfort or safety. Darting from room to room, I looked for danger in everything—in a juice carton left on the counter, a pair of shoes not properly tucked into the closet, a sleepover party invitation I knew would be a point of conflict.

But these rituals never really paid off, and there was still always a trigger lying inconspicuously in the house. And I learned over and over again from this dreaded routine that I would never be good enough to keep him from flying into a rage.

I learned from my dad that my motives were bad, that I had secretly wanted to make him upset, that my ultimate goal was to disrespect him when I knew all I had truly wanted was to talk to him about how my day went. I felt insane when he would accuse me of these things, and then try to convince me that he had never actually said that. I felt like my thoughts weren’t my thoughts, that my perception was drastically off, that my actions never aligned with my intentions—do I ever wish I could have been acquainted with the term “gaslighting” earlier in my life.

Emotional abuse is horrible at any juncture of life, but experiencing it in childhood and adolescence has shaped the way I’ve grown to think about myself and the world around me. As I moved through my teenage years, I brought the same assumptions to relationships beyond my family: That I was defective, that I had to be on guard at all times as to not upset anyone, that I wasn’t good enough, and, ultimately, that it was only a matter of time until the ones I cared about would leave me.

As a teenager I began self-harming, binge drinking with intent to numb, and struggled with increasingly bad panic attacks and depression. Outside the self-loathing noise reverberating through my brain was that same voice, this time telling me repeatedly that he couldn’t wait for me to move out.

I’ve since taken on university and entered my 20s, participated in several rounds of intensive therapy, and I still haven’t found peace in my relationship with my father. Sometimes I wonder if cutting him off would be best, but in my heart I know I’ll never be able to do it.

Because that’s the unfortunate paradox of emotional trauma: Even if someone inflicts wounds that might last for a lifetime, it can be extremely difficult to hate them, to write them off and remove them from your life. Especially when the abuse is coming from a figure traditionally or culturally propped up as essential to our lives.

Ending a relationship with a parent is tumultuous business, and the effects usually domino through the family. Although everyone will tell me that my mental health comes first, when I weigh my options it seems selfish to not just suck it up and spare my family the hurt and shame associated with estrangement.

For some these feelings might have roots in their cultural background. For me, it’s the paralyzing fear of hurting my family mixed with the misguided hope that one day I might be good enough to fix things.

My dad cheered me on and told me he was proud of me when I graduated high school, when I won hockey MVP, when I got my first job while in school. He was chatty and charming with my first boyfriend, and occasionally will proudly say that I “get that trait from him.” He helped me learn how to drive, coached me in soccer, taught me how to skate, and quizzed me for biology tests.

Although the abuse would return like clockwork, there were moments of connection that I always wished I could make last just a little bit longer. I always wondered why I couldn’t keep up a good relationship with him, what I could have done differently. It’s a question I’ve wrestled with as far back as I can remember.

When I struggle with this, I try to remember that it is never a child’s responsibility to be the adult in a family dynamic. That even if there were times that I might not have handled things with my adult decision-making skills, that this isn’t a fair standard to hold a child to.

But now more than ever, I’m trying to come to terms with accepting my trauma, and to not see it as a personal defect.

This isn’t about blaming my abuser, but understanding that my childhood lacked the emotional stability that’s so crucial for healthy development. It’s not about carrying grudges, but setting boundaries with what I ask for and discuss with my father in adulthood. It’s about realizing and accepting, no matter how upsetting the thought may be, that I have to find alternate sources of emotional support and love.

It’s about growing into the idea that I am worthy and capable of healthy love, and finding support in those who will remind me of that fact until I believe it.