Looking beyond the media horror stories to the reality of civilian lives

The term “warzone” is often used by the media to add a level of urgency and drama to any number of regional conflicts. Without further context, the word tends to conjure up images of bloodied soldiers skulking around bombed out and long-abandoned villages, devoid of their displaced civilian population.

However, for all but the most extreme conflicts, this mental image is not only hopelessly inaccurate, it’s harmful to our understanding of the world, particularly the Global South where these narratives hold most prevalent, and the direction of our foreign intervention. In 2016 I had the opportunity to travel through parts of the Middle East and the Pamir Region of Central Asia. The mountain range and its foothills cover parts of North Eastern Afghanistan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. We were warned by friends, embassy staff, and media reports that entering the region as tourists was guaranteed trouble—that could not be further from the truth.

Paranoia has denied world travellers from so many colourful locations around the world. Travelling through these so-called conflict zones has been an incredibly rewarding experience, and I hope that sharing what it taught me will provide some insight for anyone uncertain of their next trip.

Life goes on

Eastern Tajikistan has faced sporadic violence since the onset of its civil war in the early ‘90s. A recent clash between government forces and Islamic militant factions left several hundred people wounded or dead mere months before I arrived in the area. I was going in expecting armed checkpoints and paranoid citizens, what I got was a quaint mountain town suffering from an unfortunate situation. Civilians were fully aware of the conflict; there was just far too much going on in their lives to waste mental energy thinking about a problem beyond their control.

It’s easy to read Al-Jazeera and assume that the overabundance of horror stories is indicative of a region in chaos. While the human suffering caused by violence cannot be understated, it is rarely as all-encompassing as the media portrays. Three months of relative peace followed by a bombing in the town square is not reported as such, we only see the attack.

You’re not special

The lead up to the trip was a constant back and forth of jokes about how stupid this entire adventure was, many of which concerned our plan if we ended up in a hostage video on the BBC. But underneath it was a genuine fear of being caught in the middle of an international conflict in an unfamiliar country.

Oddly enough, this fear ended up being realized far earlier than we planned as the 2016 Turkish coup broke out just as we passed through the area. As we discussed calling off the whole ordeal altogether, we came to a surprisingly liberating realization—no one could care less about who we were or what we were doing in the region. I was not a diplomat, a soldier, or even a prominent journalist. At my best, I was a mildly interesting drinking partner, or a clueless tourist at my worst.

The narcissistic paranoia of being antagonized by a radical faction quickly melts away when you realize your value as a hostage is roughly the price of two kebabs and a box of cigarettes.

Photo: Eric Davison.

Counties are not real

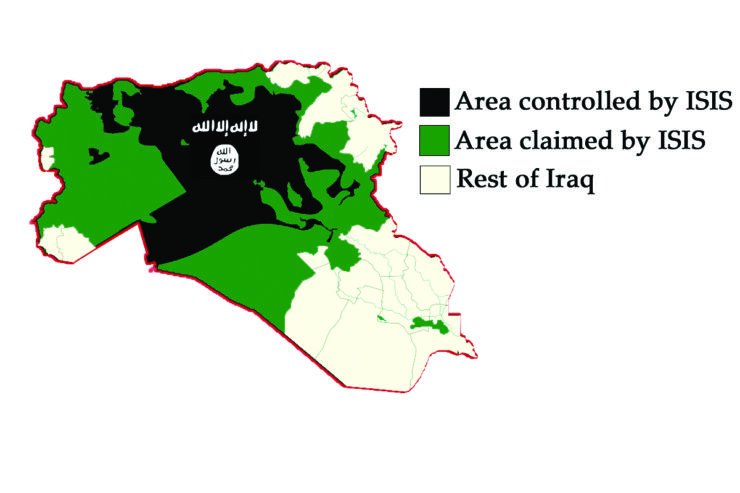

Citizens of stable states often take defined jurisdictions and political status for granted. Looking at a map with all of its lines and coloured countries suggest a much more orderly world than the reality. The Pamir region’s official borders look like a work of absurdist art without taking into account the land claims by Russia, China, or the patchwork of pseudo-states that lay claim to the countryside.

A 40-year-old Tajik could have lived a life under five governments without leaving his hometown. Vast stretches of borders are often not enforced, and even clear laws are uncommon outside of the largest cities where police often lack the resources to do much more than occasional patrols. The western sense of national identity and patriotism almost seems absurd in regions where a clean line can’t even be drawn between neighbouring states.

Terrorists are not born with devil horns

The slow descent into militancy often begins with naive optimism. Everyone had a story about a family friend who was lost to radicalism, or a positive movement turned sour by an ill-intentioned leader. It’s all too easy to dehumanize terrorists and paint regional loyalty in broad strokes without acknowledging the stress and manipulation that turns promising kids into murderers.

Parents would often discuss the children lost to radicalism the same way they would address a death. In both instances, the child that they knew was never coming back. So long as there are hungry teenagers left in the world, the supply of recruits will not cease. Realizing that leads to recognition of the absurdity of our current approach to preventing terror around the world.