The complex dynamics of the Canada-U.S. bilateral relationship

In 1969, former prime minister Pierre Trudeau described the relationship between Canada and the United States in a memorable analogy.

“Living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast, if I can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt,” he said.

His metaphor colourfully captured the complex and often uneven dynamics that are at play between the two countries. Since 1969, the relationship has had its ups and downs, and today, Canadians find themselves near a beast — if you can call it that — that has become more unpredictable than ever before.

A tale of two countries

“We are among the closest collaborators — it’s a unique and special relationship between Canada and the United States,” says Donald Abelson, director of St. Francis Xavier University’s Brian Mulroney Institute of Government.

“Certainly on the trade front — we trade in excess of a billion dollars a day in two way trade. Not to say we haven’t had our differences with the United States, we often have, our prime minister has not always gotten along well with the US president. But I think both countries realize how important the relationship is and that we both need to make an appropriate investment.”

In the globalized world, there are many close bilateral or multilateral relationships. Kim Nossal, the director of the Centre for International and Defence Policy and a former executive director of the Queen’s School of Policy Studies, cites the European Union as the world’s closest. But Canada and the United States remain a prominent example of cultural and economic cooperation between nations.

“Canada and the U.S. would definitely be second, in the sense that there are so many linkages across the border,” he says.

Brian Bow, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute and professor at Dalhousie University’s department of political science, says that the close relationship is an inevitability dictated by the region’s shared history.

“They’ve always been similar in a lot of ways, partly because they were settled in the same kind of way by most of the same kind of people around the same time,” Bow says. “A lot of the things that happen in Canadian historical development are parallels with the U.S.”

“There’s always been that closeness,” says Nossal. “Strategically, economically — you look at the pattern of American investment in Canada over the course of the 20th century, and you look at the patterns of trade over the course of the 20th century — the 20th century is a story of us becoming more economically integrated with the United States.”

“Culturally, you can go back to the 1920s and the emergence of the cinema to see voices in Canada that are worried about how Americanized people in Canada are becoming as a consequence of culture.”

That said, there have been times throughout both countries’ histories when they have parted in terms of ideology and policy.

“There have definitely been times when we’ve been at odds with the Americans, and disagreed with them on more things than we agree,” says Bow. “The 1960s and 1970s were a time when I would say that tension was quite noticeable.”

“It was possible back then for politicians to run on openly un-American platforms, and it was a popular thing to play up how different we were from the U.S., that resonated with Canadians. The reasons for that are fairly clear cut: the Vietnam War, and the violence surrounding the civil rights movement.”

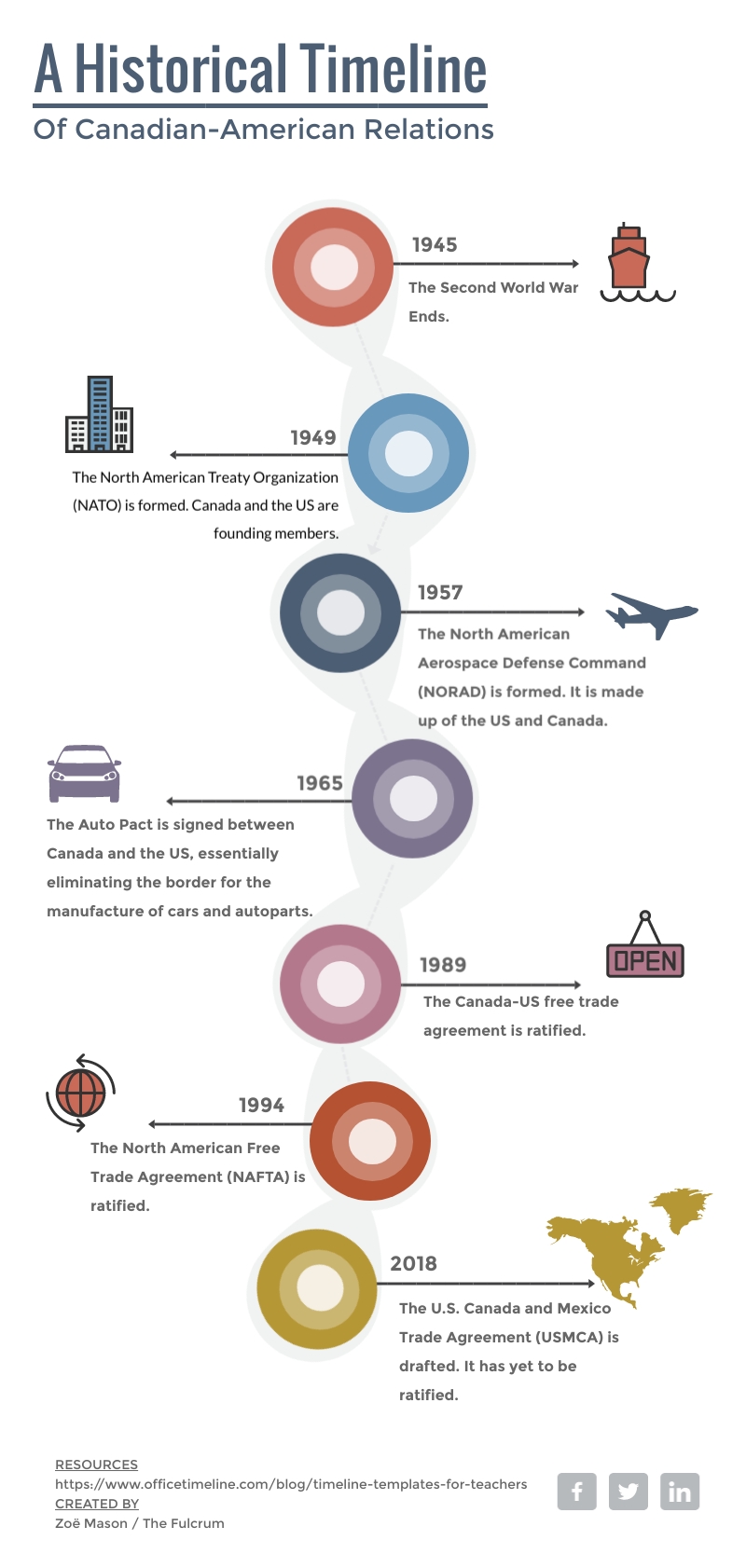

There is generally consensus that the relationship the two countries share today is largely a product of the series of trade deals that characterized the late 20th century: first, the Auto Pact in 1965, then the Canada-U.S. Trade agreement of 1989, and finally the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994.

“All of those processes and institutions reflected in a sense what was happening in the marketplace, and inspired what subsequently happened in the marketplace,” says Nossal. “Simply look at the vast increase in wealth in central Canada that came after the Auto Pact was introduced in ’65. That just had a huge and very positive effect on Canadian economic growth. Ditto for U.S.-Canada free trade and ditto for NAFTA,” says Nossal.

He adds that since becoming allies after the Second World War, the United States and Canada as state entities have only continued to grow closer. Nossal says he thinks questions regarding tension between the nations require reframing.

“The real question to ask is, not has Canada, this singularity, been close to the U.S., this singularity, but instead, things like how have different governments and different heads of government, how have they gotten on?”

This refocusing makes rises in anti-American sentiment easier to identify. For example, 20th prime minister Jean Chretien was able to campaign on anti-Americanism in the late 1990s during the presidency of George H.W. Bush. However, this relationship has grown more complex in the modern day.

Politics in the shadow of the beast

Today, the relationship between current U.S. President Donald Trump and Justin Trudeau’s government is tense, but the tensions are largely subtle and have yet to escalate into anything politically salient. That said, Bow says the undertones of recent campaigns have contained traces of anti-Americanism.

“I think the Trudeau government Liberals ran on a platform that was, in 2015, when they were elected last time,” he says. “Some of the subtexts in their campaign ads implied that the Harper way of doing things was like the American way of doing things, and they want to restore some of the Canadian versions of policy that you associate with the Liberal brand.”

“What’s really interesting about the Trump administration is that Justin Trudeau has been exceedingly careful not to allow either his government, his ministers, or his backbenchers to sound the least bit anti-American,” says Nossal. There’s lots of anti-Trumpism around, but even then, you will not find much open anti-Trumpism on the part of his ministers or MPs. No one on the Liberal side would ever dream of doing what Singh did, and that is to welcome the impeachment of Donald Trump.”

Nossal agrees that current political circumstances are such that anti-American sentiment is something that resonates with Canadian voters — although Canadians understand it is something that must remain muted.

“I think that most Canadians understand, is that this president — so thin-skinned, so unpredictable, so disliking friends, allies, and neighbours as Trump does — that one needs to be really, really careful about how one treats the United States president,” Nossal says. “You get a real paradox. You’ve got a huge degree of antipathy towards Donald Trump, but you have not seen the periodic rise of anti-Americanism in Canada the way we have previous years.”

The Canadian-American relationship is always at the forefront of Canadian policy-making, and for that reason, Canada is forced to make concessions in order to support American interests.

“In terms of the big picture, do the countries benefit from working more closely together? They generally do. But Canada has to work just a little bit harder in order to make sure the relationship remains intact,” says Abelson. “It’s a balancing act, it’s a very fine line, because Canadians are sensitive to political leaders who want to maintain too close of a relationship with the United States.”

While American influence is straightforward, any influence Canada exercises in return is much more convoluted.

“The American system is extremely open compared to other political systems, and very fragmented, and that gives us lots of opportunities to try to influence policy outcomes in the U.S. by making alliances with various groups,” says Bow. “A business association or industry whose interests are aligned with Canada’s, we could do things to support them, or we could lobby Congress.”

“There are lots of ways where, even if we disagree with the White House on something, we might have implicit or explicit allies within the US and we work transnationally with them to try to influence the policy process and get the outcome we want.”

Nossal is less convinced that Canadian interests are heard at all in the United States.

“Does the United States, and do Americans, take Canadian interests into account? The short answer: absolutely not,” he says.

“We have to always struggle to ensure that if something the Americans do is going to hurt us, that they be made aware of the likely hurt,” Nossal says. “The fact is that the United States is 10 times larger than we are, it is the dominant hegemon, it really doesn’t matter to Americans who is going to be hurt on their borders.”

American influence on Canadian polls

Canadians are constantly exposed to the spectacle of American politics. The Trump presidency has dominated the media for the past four years, a period that has also been characterized by right-wing, populist governments being elected around the globe.

Some worry that similar movements could take place in Canada, but Bow is not convinced that Canada is heading down the same path.

“We’ve seen that there are little signs that Trumpism has had a contagion effect in Canada, and it has a sort of played itself out in for example Bernier’s People’s Party (of Canada), and the numbers of people that have strong anti-immigration views that they are willing to voice publicly in ways that they weren’t before,” he says.

“Certainly I think there’s been a concern among some Canadians at this kind of populist movement will take root in Canada. Some people turn to what’s going on in Queens Park with Doug Ford,” says Abelson. (But) I think there are enough Canadians who are concerned about the direction that American politics has gone and how politically toxic and increasingly polarized the country has become.”

“y hope is that cooler heads will prevail. There are certain things the United States does that we would do well to embrace and there are other things that should probably keep us up late at night,” Abelson adds.

Nossal says he thinks that Trump’s unique policy and unpredictability means that it’s impossible to gauge how he could influence Canadian elections in any direct way.

“You might say ‘well, the Conservatives will follow Republican trends.’ Even then, because the Republican Party has departed so far from normal conservatism, as it’s become the party of Trump — Mr. Trump defies any kind of clear categorization,” he says.

“Some days he gets up and he’s a populist, some days he gets up and he’s an authoritarian, some days he gets up and he’s a white nationalist. Truly, one can’t figure out where his ideology is and I’m one of those who believes that he doesn’t actually have an ideology. So without that it becomes then very difficult to track what may or may not happen in Canada.”

Nossal suggests the sensationalization of the American political fiasco is more likely to push Canadians in the opposite direction. He disagrees that Bernier’s PPC is any real manifestation of Trumpist policy in Canada, but asserts that it is actually contained as a consequence of the Canadian fear of Trumpism.

“Canadian politics has kind of shifted I would say almost to the opposite side, that Canadians have become exceedingly nervous about the possibility that we’re going to turn like the United States,” Nossal says.

“I think (it’s) one of the reasons why Maxime Bernier is suffering the fate that he’s suffering. In other words, people are far more nervous about embracing him than I thought they would have been if Trump hadn’t enjoyed the success that he has.”

The future of UMSCA, the future of the U.S. and Canada

In this election, it seems the biggest challenge presented by the unbalanced bilateral dynamic is less political and more economic. While trade agreements have served to bring the two countries closer in the past, the currently unratified U.S. Mexico Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA) could stand to tear them apart.

“This was a campaign issue for Donald Trump, he maintained on a number of occasions that the NAFTA was the worst trade deal ever, which is certainly not the case, and wanted to make sure … that the agreement was renegotiated and that the United States would extract even more concessions,” says Abelson.

“The trade relationship with the United States is vital to our economic prosperity, I think Canada did very well during the negotiations in terms of protecting our interests, and we would certainly have to regroup in the event that the agreement wasn’t ratified.”

Nossal agrees that an agreement is important, but he doesn’t see the potential failure to ratify USMCA as terribly threatening to Canada.

“If the Americans fail to ratify this, then from Canada’s perspective, the default is NAFTA. Unless Trump does something really, really stupid, like denounce NAFTA — and the fact is that there ae lots of voices in the United States, including Trump’s big donors, that are basically telling the president ‘don’t dump NAFTA.’”

“The fact is that the United States did very well by NAFTA, as Canada and Mexico did. But here we have a president who doesn’t understand anything about the modern economy. He has a sort of 16th-century mercantilist view of international trade,” says Nossal.

Love it or hate it, Canada is destined to continue the balancing act of managing regional interests for a long time to come.

Nossal says that “short of a major, major disruption in the capitalist economy,” he cannot imagine a future in which Canada and the United States cease their close collaboration.

Bow, however, thinks that Canada distancing itself from the United States is entirely possible, and perhaps already happening.

“Canada and the U.S. are very much out of step on a bunch of different things, and the Canadian government has been casting around looking for ways to do things on its own or do things in partnership with other countries,” he says.

“I think that’s a debate we used to have regularly, like ‘should we do more acting on our own, separate from the U.S.?’ And we don’t have that debate as often, but I feel like right now, in this Trump moment, people are receptive to that argument.”

He cites initiatives Canada has undertaken on child soldiers and on training peace support operations with its European allies and the United Nations as examples of recent, more independent Canadian policy-making.

Abelson isn’t so sure.

“These are discussions that have been going on for years. Is there a third option available for Canada? At the end of the day, we can work on our relationships with other countries, strengthen those bonds, but not at the expense of our relationship with the United States,” he says.

“Given our geography and our history, given our shared values on many issues, it’s difficult to imagine that Canada would be able to benefit economically, in a security way, or environmentally without the United States.”

Canada and its leaders will continue to manage the behemoth that is the United States for the foreseeable future. The international sphere is chaotic — famously, it’s described in realist theory as anarchic. So although it’s a mighty task, there are certainly worse things than having a beast on your side.