The restaurant served the Ottawa community for 49 years

Translations by Shino Togami

This feature was originally written April 30, 2024.

I met Masanori Arai (荒井) on the front steps of Shino Togami’s house one evening in October. He and I had arrived at the same time, and while there was evidently a small language barrier on my part, he greeted me very warmly, given the dreary circumstances.

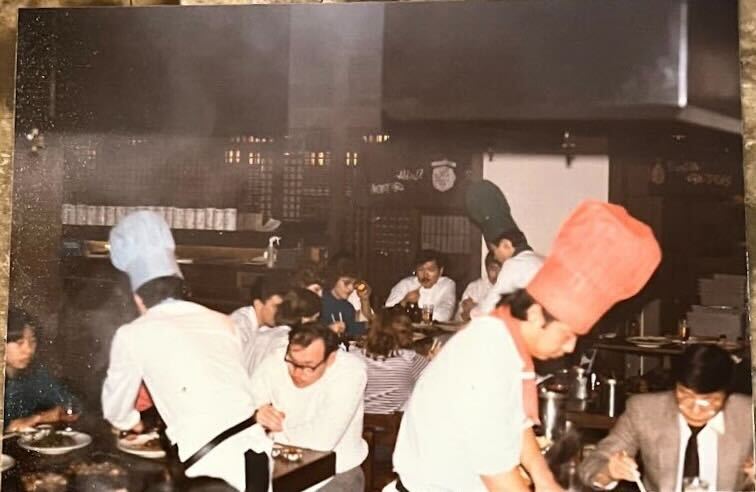

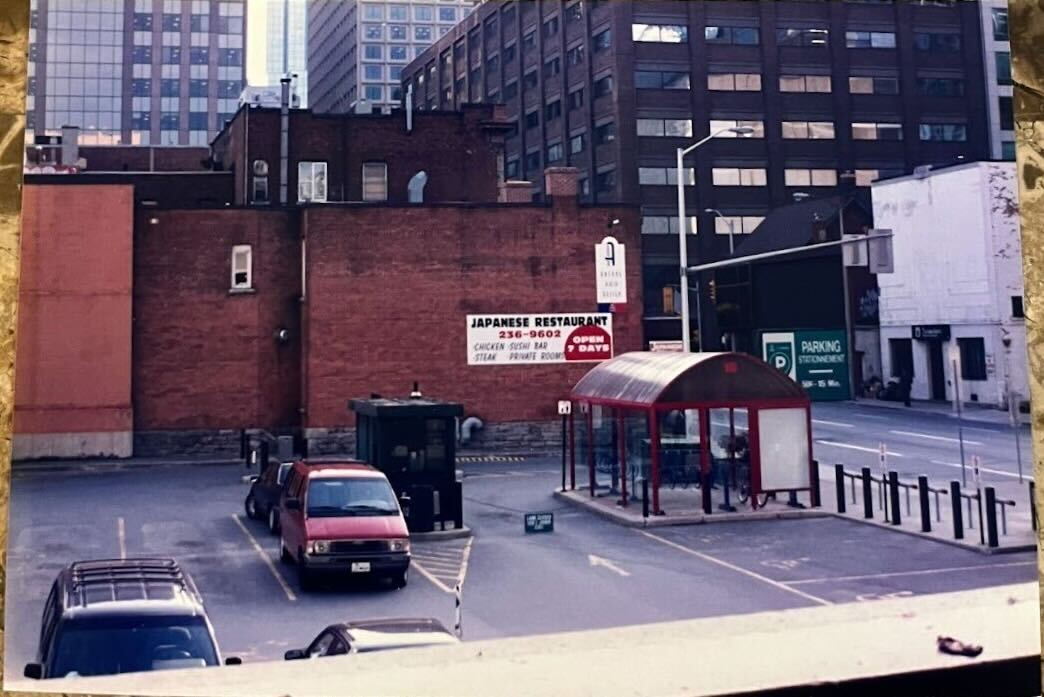

In July of 2023, Arai and the staff of C’est Japon A Suisha and formerly Suisha Gardens were forced to permanently close their doors after 49 years of serving the Ottawa community. The restaurant, located at 208 Slater St, was frequented by students and embassy workers alike before its permanent closure.

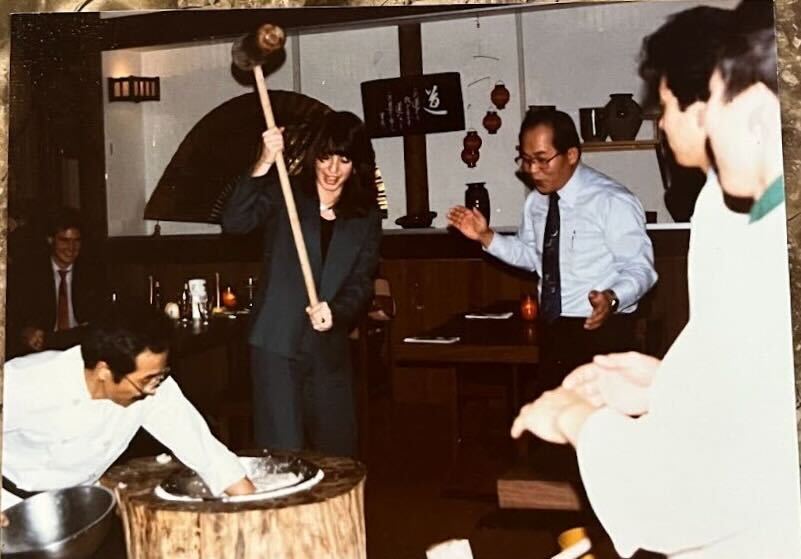

Togami, our translator for the evening, led both of us inside from the cold rain. A Fukuoka native, she had decorated her house beautifully for Arai’s visit, amongst which was a massive sake barrel near the front door. They exchanged very warm greetings before she led the both of us to her dining room/makeshift recording studio, her table topped with red bean cakes and green tea.

Following their closure, Arai and I exchanged emails, during which he explained the circumstances of their closure. “We must close the restaurant due to the lease agreement with our landlord. They will build a condominium in the future, so there’s no choice, we have to move out by the end of July.”

Before sitting at the table, Arai gave us a series of gifts — various chocolates and a keychain from their closing celebration.

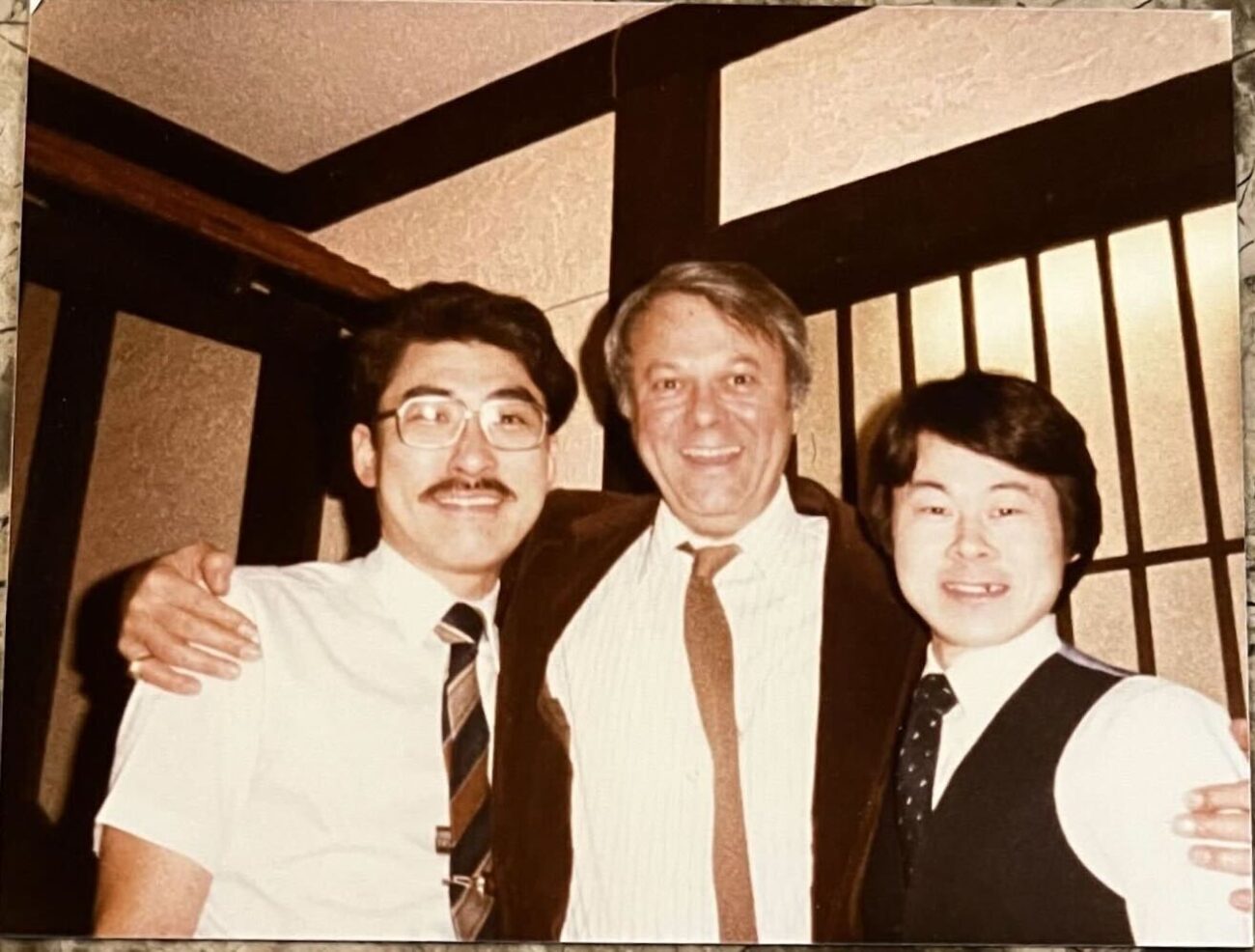

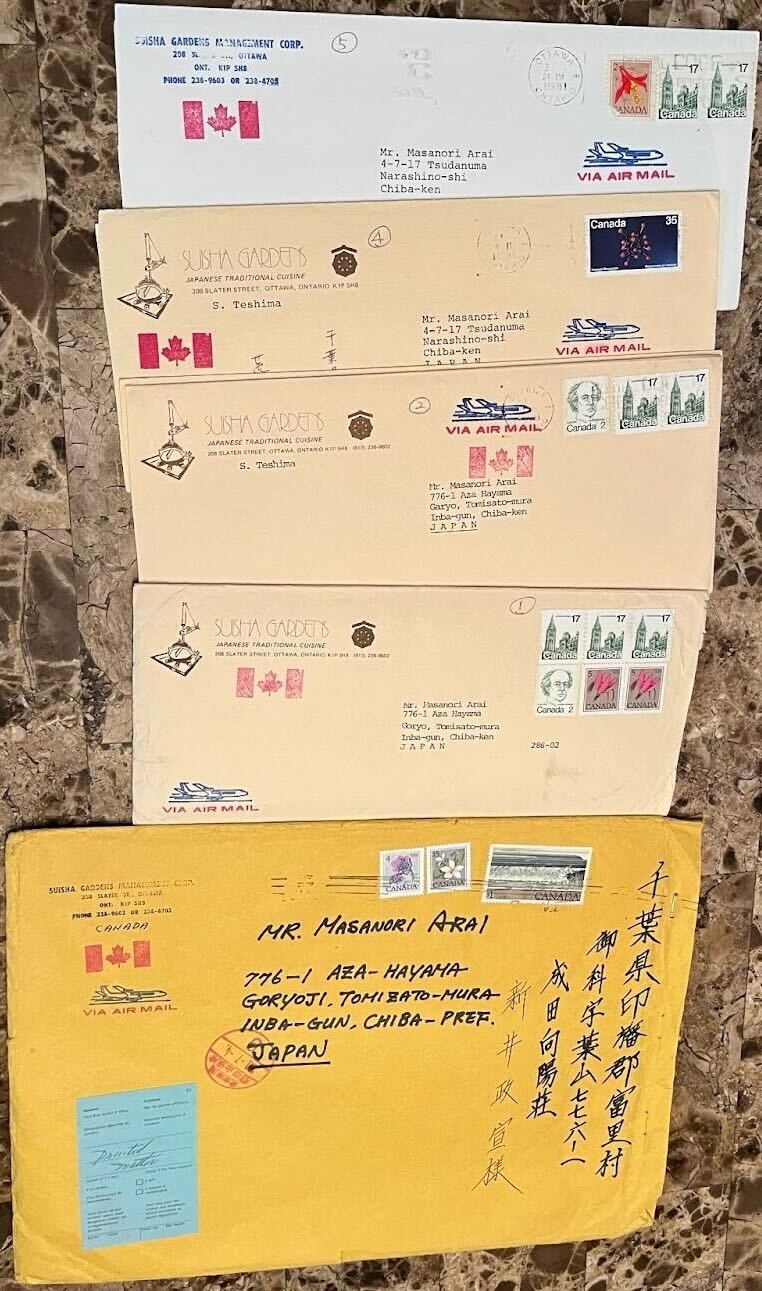

Arai was 19 when he first read about Suisha Gardens. He was working as a bartender at the No. 4 Satellite at Narita in 1979 when he first read about the Japanese restaurant, and its owner Frank Teshima (手島重成).

“At that time, I picked up a magazine that I saw at a bookstore in the middle of the night when I had finished work, and read the article. When I saw it, I was moved and wrote a letter.”

Arai had inquired about moving from Sendai, a city in Japan, to work in Frank’s restaurant. Traveling was not new to him – he had studied English as a part-time high school student in Boston in 1977. Despite this, Teshima rejected his request, stating that he was far too young.

Arai described the first exchange of letters with Teshima: “‘I’m asking you to hire me even if I have to wash dishes in the future.’ So I sent a letter, and about 3 months later I received a reply saying, ‘No, you are still young, so you should reconsider your life.’ After about 3 months, I just couldn’t give up and wrote the same letter again.”

During these exchanges, Teshima suggested Arai apply to the international overseas agencies if he was still interested, but as he stated “there was no intention to hire directly.” About a year later, Teshima and the company president opened their third store in Niagara. Arai then had interviews for other jobs in Sapporo, Tokyo, Osaka, Fukuoka (all over Japan).

He eventually stayed in a dormitory in Tomisato Village and then an apartment in Tsundanuma, all while working at Narita Airport.

He applied to the Niagara store, and with over 600 people applying, he did not get accepted. He had failed the interview and was very frustrated by it. “I thought there was no point in holding out any longer, so I continued at Narita Airport, worked a little harder at work, saved up some money, and, I didn’t know anything about it, and left.”

He then decided to hike from Alaska to Chile, stopping by the Ottawa location on the way. But despite seeing the store in person, the feeling of giving up couldn’t leave him.

“After seeing this store, I decided to say goodbye to North America … I stopped by Ottawa on the way home and went and looked at it, but I still thought about giving up.”

However, things changed when he returned.

“When I got back to my apartment after work, there was a piece of paper standing by the door, and it was a telegram… When I opened the message, it was Canada’s employment agency, CEC, and that they had received permission from the Empowerment Center to hire me. Therefore, I was asked to go to the Canadian Embassy and complete the immigration procedures.”

In that time span, Arai had applied four times to Suisha Gardens, being rejected on three of the attempts. With this opportunity, Arai completed the immigration procedures and left Japan.

While Arai speaks humbly about his hard work, he does admit there was a good amount of luck involved in getting to where he was.

Arai first started working at the Ottawa Suisha Gardens for a month before being moved to the Halifax location, and continued to work there until 1984.

“I ended up staying in Halifax until May of 1984, which was only six months. That Niagara store was busy heading into the summer, so I was ordered to come and help out at the Niagara store for three months… but around the end of September, the store manager, and vice president retired. So in 1984, I was 20…I was suddenly asked to become a store manager. From then until 1988, I was a store manager in Niagara.”

Arai described how busy and quiet it got seasonally, with the restaurant being packed every day in the summer, with long quiet periods during the winter.

For several reasons, he was not happy with working in Niagara and around late October of ‘88, quit. “I quit … I just didn’t see eye to eye with that president. I wanted to work all year round rather than doing seasonal work, so I moved to Ottawa on my own.”

Arai was doing other work in Ottawa before Teshima reached out. “He asked me to come back, so I came back. I think it was around October or late September of 1991. And it feels like I was able to start again from there.”

He worked at the Ottawa location from then but still felt that he wanted things done differently. “I worked there until 1994, and then, what can I say, I met the president for a while and met a few more people, and then I thought about quitting again.” However, this time, he would be bold about it – asking to buy the original Ottawa location from Teshima.

His reasoning was thus, “I don’t have any more money. I have no academic background. There is nothing. I have no choice but to do it.” Raising some money from his senior coworkers at Tokyo Airport, he acquired enough to propose an offer to Teshima.

Arai describes his thinking at the time, “I’m going to talk to Frank. I talked to the president, and he asked me if I wanted to stay in Ottawa or in Niagara. But isn’t Ottawa the president’s headquarters? It’s the original main store…However, the president chose me because he was a big person. Which one do you prefer? Well, I love Ottawa. Okay, so let’s do Ottawa.”

On February 15, 1995, Arai reopened the restaurant, now under his management.

Due to the contract, the store’s name would remain Suisha Gardens for ten years, before being renamed to C’est Japon a Suisha.

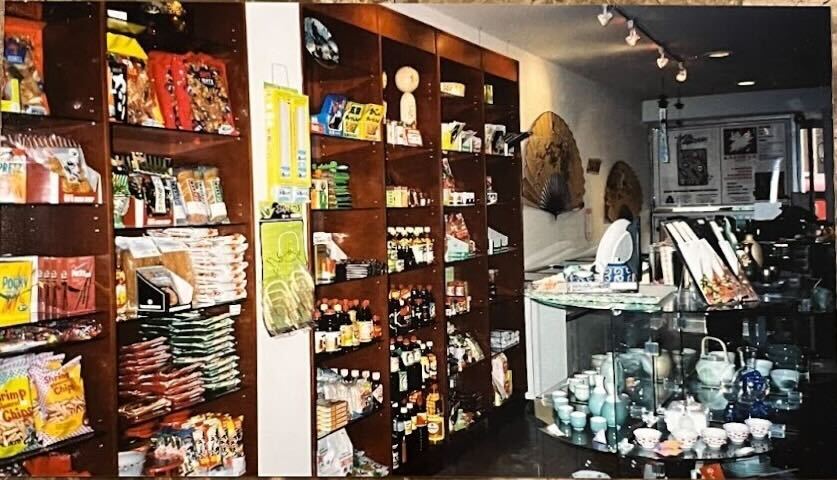

During this time, Arai also helped with the Niagara store and eventually helped develop a Japanese grocery store in the building next door, selling imported foods and wares.

The grocery store would eventually close, but Arai looked back on it fondly and with a sense of sadness.

“It closed around 2007. It was a little difficult to find people. [They] had to be Japanese. As for Japanese women, they have to go back to their hometowns… So, if that happens, I would have to hire someone again to compensate. So, we had to arrange some people, and it was still a little early at that time. In terms of those products, it was a time when Japanese products were not yet well known.”

Amidst reminiscing and the plans for another restaurant, Togami thanked Arai for the service he has done for people like her that have dined at the establishment.

“The biggest difference is our culture,” said Arai. Since we are Japanese, that is what hospitality means. Well, to put it simply, this hospitality is hospitality, as everyone imagines, but there is a difference between service, hospitality, and omotenashi [culturally-specific mindful hospitality], and there are some subtle differences that I have recently learned.”…

Arai continued. “However, our culture has been cultivated over many years, and has become normal for a long time, so it is difficult to understand how we feel about it. Because you’re not conscious. It just comes naturally. But this hospitality is still the core of our basics, and Japanese people think of the other person first, and think of other people besides themselves. So, I guess the idea of welcoming customers while putting their heart and soul to work has been naturally cultivated and has been practiced for generations…”

Arai also talked about the years leading up to the Ottawa location’s closure, speaking fondly about the people he was working with. “Most of the people are now my age, so it’s going to be quite difficult for these people from now on.”

Arai had wanted one of the restaurant’s senior members to take over, but with the landlord’s plans to transform the location into housing, he has had to change his plans a bit.

Now, Arai plans to start a consulting business for Japanese restaurants in Canada. Arai talked about hospitality, a style uniquely Japanese, that future restaurants need. “A difference between service, hospitality, and omotenashi … this hospitality is still the core of our basics, and Japanese people think of the other person first, and think of other people besides themselves”.

He then went on to say that if there are people who want to open Japanese restaurants but aren’t Japanese, he wants to help them.

“The people who are doing it… they want to do it with a Japanese feel, not just a menu. If there are people like that… I want to help them”.

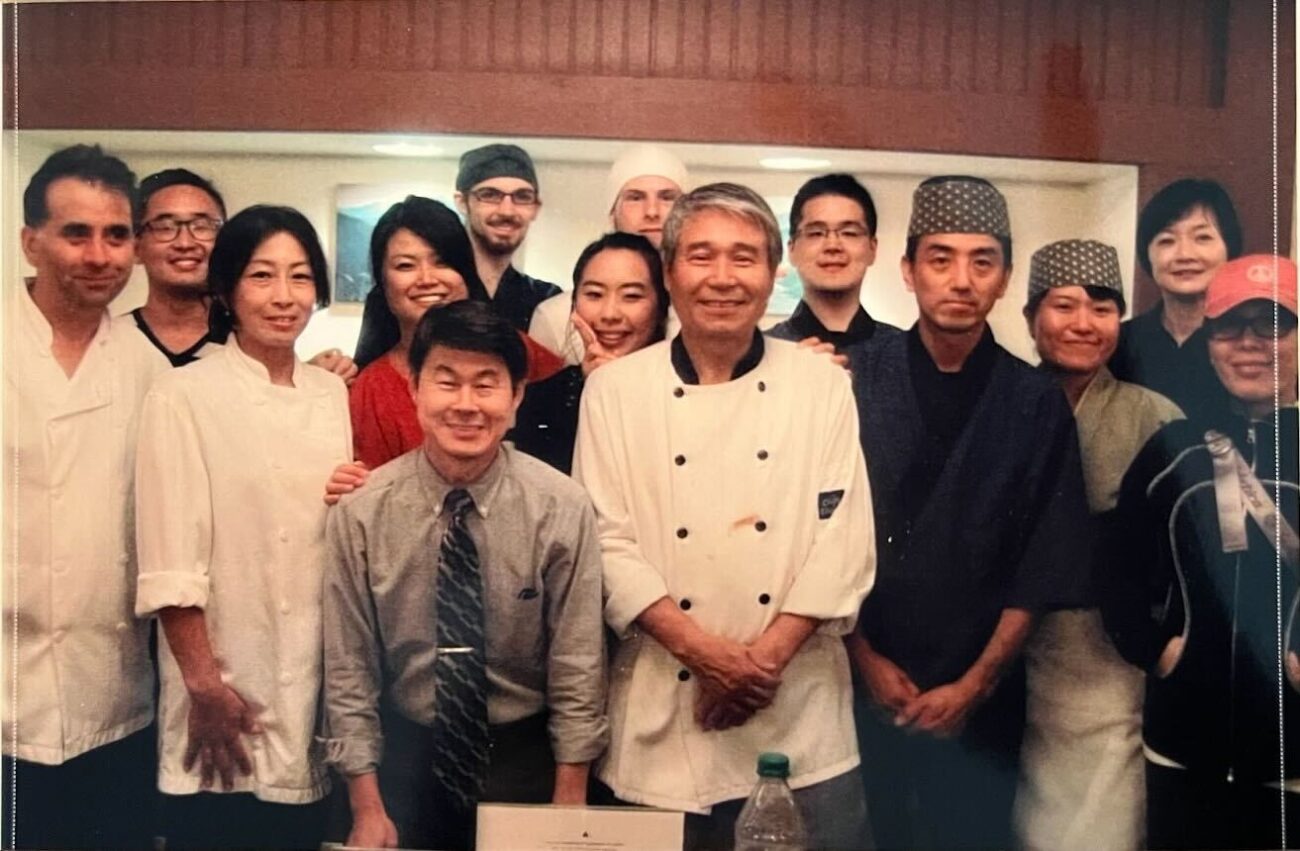

In 2022, many of the former Suisha Garden staff returned from all over Canada and the US to commemorate Teshima’s first Japanese restaurant in Canada. Arai jokes, “40 people came. I’m here too, but I’m 63. We’re all seniors.”

Suisha Gardens Reunion, 2022. Photo/Provided

We packed up for the night. By then, over two hours had passed. As we sat there, Togami thanked Arai, in earnest, for everything.

“Of course the food is delicious, but it’s the people who come, or rather the people at the restaurant, who are the ones who keep people. It’s stuck in my heart… there’s a big difference between having something and not having it, and it’s more delicious than just going into any restaurant and being served delicious food. The atmosphere of the store is nice. It feels like I’m back in Japan. It has a rural feel. And if the person who brings the food is really good, then it would be perfect. If you put your pinky between your fingers and sit there quietly, you’ll feel like you’ve come to a really nice restaurant. That’s when I realized that it was a good store. So thank you very much”.

Nicholas Socholotiuk served as the Fulcrum’s staff writer for the 2023-24 publishing year.