An artistic response to the housing crisis

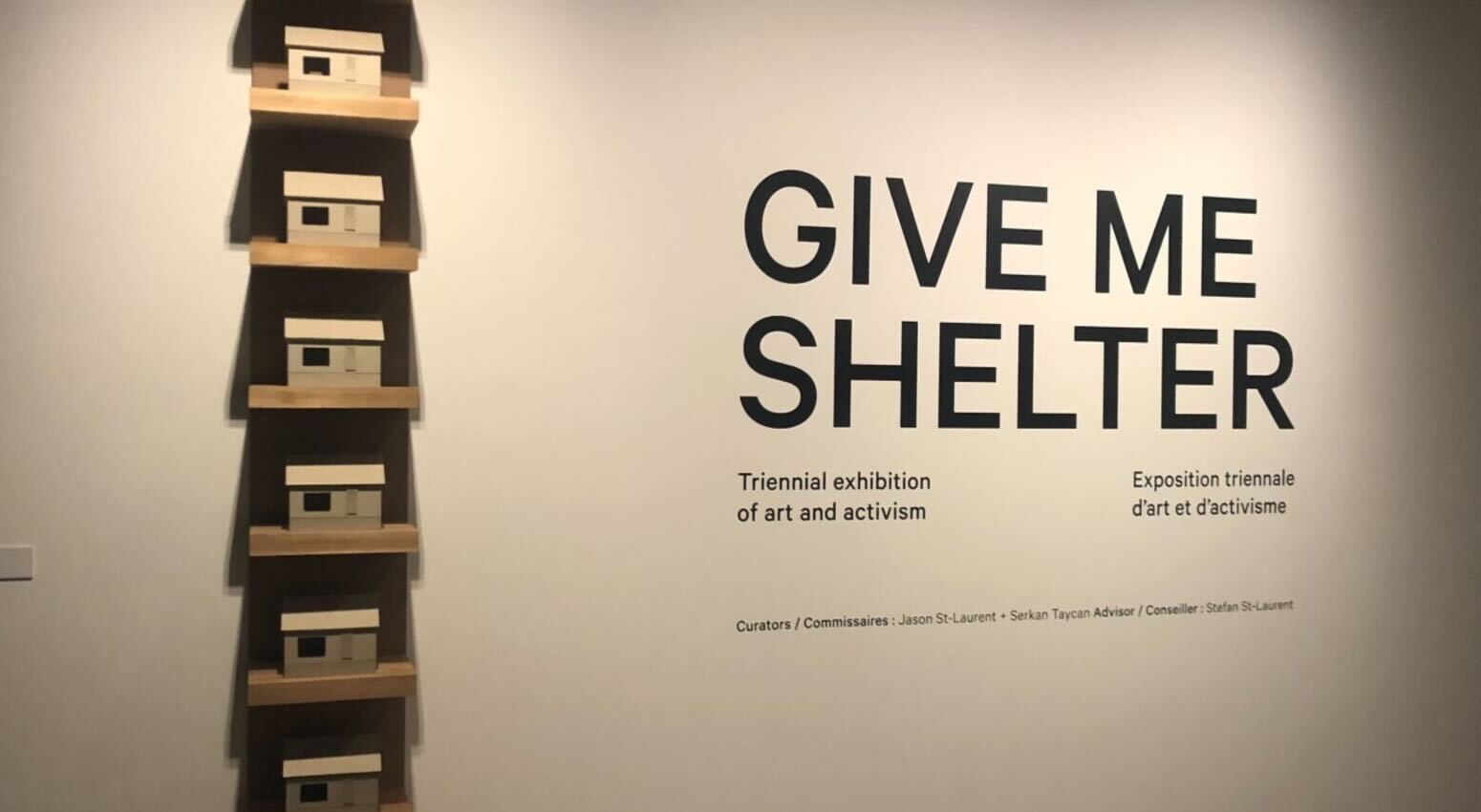

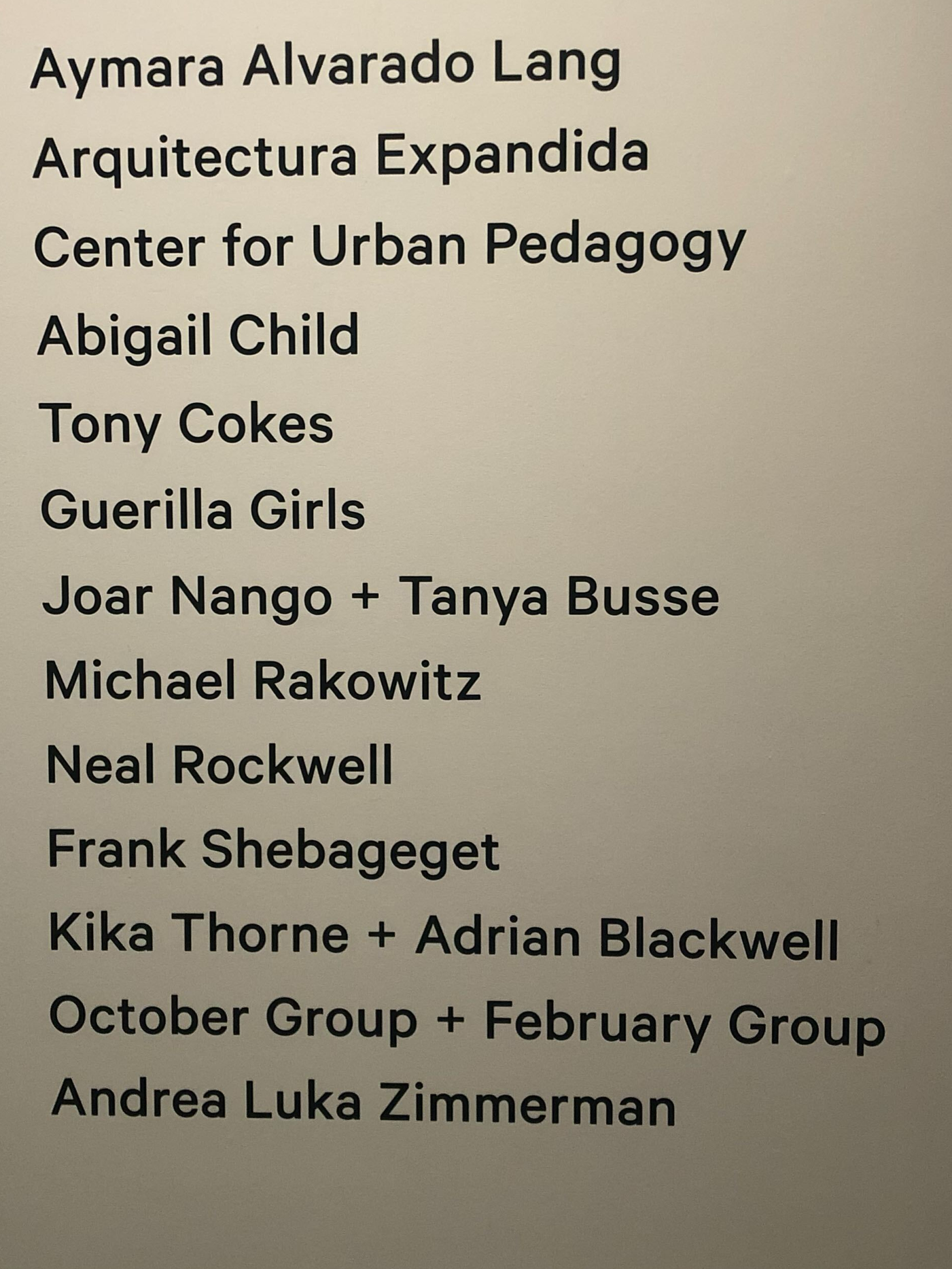

The Give Me Shelter exhibition at the SAW Centre, features 12 artistic responses to the issues of housing and homelessness in and out of Canada. Inaugurated on Oct. 11, the triennial exhibition is both eye-opening and provocative. From community advocacy and solidarity movements, to enlightenment campaigns and individual action, the message of Give Me Shelter is that there is something everyone can do.

Not only is the exhibition a great avenue to learn about what can be done in response to housing issues, but it also serves as a place to more deeply understand problems surrounding housing internationally and in Canada.

To further emphasize these points, the opening of the exhibition featured a panel discussion that was oriented around creating safe spaces for people affected by unstable housing in Canada. It reminded people that housing is more than just an issue or a living space — it’s about protecting homes.

Give Me Shelter highlights older issues and community works surrounding housing problems in Canada. However, it also showcases recent community action surrounding newer issues. One of such is shown in the digital prints of Neal Rockwell, an investigative journalist, filmmaker and writer. Rockwell heard the term ‘financialized landlord’ for the first time while he was documenting the happenings of Herongate, Ottawa.

Herongate was a racially-diverse neighbourhood in Ottawa that was home to a large community of immigrants of visible minority. After it was bought by financialized landlords (large, corporate entities that manage rental properties for profit), it was slated for a demoviction. This eventually resulted in the eviction of over 105 (about 400 people) households overnight. After experiencing this, Rockwell was prompted to start his investigation on financialized landlords.

“I heard this term ‘financialized landlord’, and I had to learn what it was. That became kind of a process for doing the project as well.” Rockwell remarked. “My first exposure to what financialized landlords were was in experience of being in those buildings and talking to those tenants. I had to understand it from the bottom up.”

The results of Rockwell’s investigations were staggering. After the data was gathered, a team began to analyze it. This involved mapping out 4,500 apartment buildings bought by financialized landlords across Canada and then looking at patterns of where they were investing.

So far, the data has shown that financialized landlords are heavily invested in buying up specifically low-income, specifically Black neighbourhoods. It was also uncovered that those landlords were funded by public pension funds in Canada. While more analysis is still to be done on the data, Rockwell’s present findings are currently a part of Give Me Shelter.

“The installation itself brings together photos and archival materials: things like freedom of information requests and other types of documents that would typically sort of inform a story, but you probably wouldn’t visibly see them in a typical new story.” Rockwell continued. “I wanted to make the documents visible to understand the reality of how bureaucracies and power structures interact with other stories to create power.”

Through documenting, Rockwell did two things: he captured the resilience of communities and uncovered the deliberate gentrification of immigrant-occupied communities like Thorncliffe Park, West Lodge Towers and Herongate. His motive behind his documentation was two-fold. He felt it would contribute to his work as a journalist, spreading awareness of issues through what he termed the ‘truth network;’ a sharing of truths through networks built on community trust. However, he was also deeply motivated as a member of society who, in his opinion, was positioned to make a difference.

“I, as a person who lives in Canada, perpetually witness the impact of the housing crisis. I’m not as directly impacted as many people, but on some level, I hope that this journalism [my work] plays a part in changing the way things are done,” Rockwell said, “ this crisis is sort of ripping apart the social fabric of cities. You can really see it in Toronto and other places as well.”

There are more startling revelations on showcase at Give Me Shelter. Anishnaabe artist, Frank Shebageget’s sculptural works, Small Village and Small Village II serve as a commentary to the impact of colonialism on architecture and housing in Canada. His work, a series of identical houses arranged in perfect symmetry, shows the standardized ‘Canadian Indian Home’ imposed by the federal government on Indigenous peoples: something that still affects many communities til today.

The homes were built with Western concepts and no consideration for the culture of the people who would be living there or the climate they would be living in. As a result, certain elements of housing that were important to Indigenous peoples’ way of life and survival in nature were erased from the homes that they would have to live in for generations. This included large, open multi-purpose spaces and spaces that connected to nature. While this may not immediately seem essential, these requirements for Indigenous housing were closely linked to Indigenous ceremonial culture, spirituality and trade.

There are pieces in the exhibition dedicated to showcasing solutions rather than uncovering issues. Printed matter and educational materials from the Center for Urban Pedagogy (CUP), a non-profit organization based in the United States, show a toolkit designed to simplify complex housing policies and urban policy in New York City. The toolkit is currently available in multiple languages to cater to the diverse linguistic needs of New York City.

While Give Me Shelter is displaying artistic interactions with housing issues around Canada and abroad, it is also giving a voice to people who are currently facing housing threats in the exhibit’s home city, Ottawa.

The Bank Block Tenants have been fighting against an N13 (renoviction notice) for almost two years. The front-facing buildings between Bank Street and Lisgar were purchased by investors, Smart Living Properties, for redevelopment and the tenants were issued N-13 eviction notices. The tenants on the block decided to stay. They mobilized as neighbours and have since written newsletters in response to public letters written by Smart Living. They have gone door-knocking and held rallies. They have also allied with the People’s Assembly on Housing.

They are currently scheduled for a hearing with Ottawa’s Landlord and Tenant Board in March 2025. A representative from the Bank Block Tenants was present at the opening of Give Me Shelter. They wanted Ottawa to know that they were still holding on and anyone who may be in their situation had hope — they were not alone.

Moreover, they took the opportunity at Give Me Shelter to remind people that Bank Block and other issues surrounding housing were not isolated. These issues eventually spread until they affect everyone.

“I think we understand that those people who are sleeping in our doorways were not born homeless. These people had homes at one point, and these people lost homes in some type of process of displacement.” Eric Roberts, a Bank Block tenant said in an interview with the Fulcrum.

“It comes down to what type of city you want to live in. You can’t really have it all. You can’t have a city where you’re gonna feel comfortable walking in all parts of the city, day and night, and also be mass displacing people left and right. If you feel like the city should only be a comfortable place for people making above a certain income, then you better not complain when you are then very quickly faced with the reality that large parts of your city become completely chaotic and miserable.”

The Bank Block tenants urge everyone to do what they can: learn more about issues, come out to show support, poster, advocate or share the news. They also had advice for anyone in their situation — facing an N13 eviction.

“Don’t sign anything, talk to your neighbours and try to have situations where you are never isolated by your landlord,” said Roberts. “Make sure that you are talking to your landlord only in a group with your neighbours.”

Overall, the Bank Block Tenants, Herongate, and others are not special circumstances. They are smaller aspects of a growing problem that people are just beginning to realize exists.

“What’s going on is important because if the investors are successful on our block, they end up adding to their portfolio. It gives them a greater capacity to absorb more vacancy and push rents higher.” Roberts said. “It’s not at a point where we’ve got three different cartels controlling housing, but it is moving in that direction. And every time a process like the one that’s going on on our block succeeds, it tends toward more like a further monopolization of the housing control.”

Give Me Shelter uncovers issues, solutions and more, presenting highly political issues through an artistic lens. This triennial exhibit is not only very relevant to our current situation in Ottawa, but also a real lesson in community mobilization and social activism.

- With files from Daniel Jones