Tamara Martinez explores this year’s shortlisted novels

It’s easy to see why the Scotiabank Giller Prize is “the first word in fiction” on the 25th anniversary of the award.

As Kamal Al-Solaylee, prominent Canadian journalist and one of this year’s five jury members puts it, “human beings are interested in stories that reflect a personal space, a zone that is visceral. Oral histories, fairytales, and folklore interest human beings. In personal terms, writers feel “a calling” to write.”

Originally founded in 1994 by Toronto businessman Jack Rabinovitch in honour of his late wife, literary journalist Doris Giller who passed away the year before, the Giller Prize honours excellence in Canadian fiction each year.

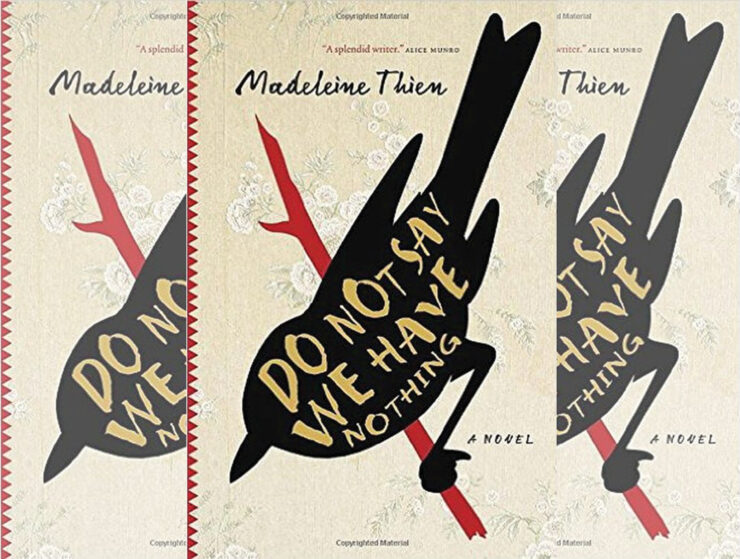

The award itself is redesigned each year by Toronto-based firm Soheil Mosun. Some of the notable past winners have included Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace (1996), Joseph Boyden’s Through Black Spruce (2008) and André Alexis’ Fifteen Dogs (2015). In 2016, the U of O’s writer-in-residence, Madeleine Thien, won for her novel, Do Not Say We Have Nothing.

In 2015 the juror panel expanded from three to five jurors, composed of members from across the globe, including the U.K. and the U.S.

“They bring a fresh perspective,” Al-Solaylee said.

The Canadian literary scene has long since talked about a “Giller Effect,” Al-Solaylee said, that follows shortlisting, longlisting and especially winning the prize, where authors see an increase in book sales and status.

Esi Edugyan took home this year’s prize and $100,000 for her novel Washington Black at a Toronto gala on Nov. 19.

“In a climate in which so many forms of truth-telling are under siege, this feels like a really wonderful and important celebration of words,” Edugyan said during her acceptance speech.

“Edugyan has written a supremely engrossing novel about friendship and love and the way identity is sometimes a far more vital act of imagination than the age in which one lives,” the jury wrote of the book.

Along with this year’s winner there were four other novels on this year’s shortlist, whose authors also took home $10,000 prizes: French Exit by Patrick deWitt, Songs for the Cold of Heart by Eric Dupont, Washington Black by Esi Edugyan, Motherhood by Sheila Heti and An Ocean of Minutes by Thea Lim. Here’s what to expect from them.

Some of the following summaries may contain spoilers.

Washington Black by Esi Edugyan, 441 pages – Winner

The novel follows 11-year-old Washington “Wash” Black, who lives in a Barbados sugar plantation in 1830. This book is about hurt and pain. It is more painful in text sometimes than what you typically would read with narratives of slavery in the southern United States in the 1870s and 1880s. The author describes the violent slavery: “Sick mend were whipped to shreds or hanged above the fields or shot.” Death is a “door”; if you are dead and wake up again in your homeland, you awake free.

Wash escapes the plantation and slavery on a flying machine, the “Cloud Cutter,” trekking across North America and eventually into the Arctic. The novel is lighter in subject in its final two sections, set in Nova Scotia and England, yet the thought of being a former slave lingers for Wash. Edugyan lives in Victoria, B.C.

French Exit by Patrick deWitt, 213 pages

I am going to ask you a number of questions about your mother: does she look, talk, and travel like Frances Price? Subtitled a “Tragedy of Manners,” French Exit is about a rich widow from New York City who moves to Île-Saint-Louis in Paris, France, after running her savings dry. She is accompanied by her son, Malcolm, and a cat, Small Frank. She is 65-years-old and Malcolm is 32-years-old. The relationship between mother and son is very important, and the text reflects that with dialogue like: “I’m going to interrogate you directly, … has anything changed in regard to your relationship with your mother?”

Frances sees herself in the following way: she was “in her bed, in her indigo robe, hair upswept, studying herself in a palm mirror and talking to Small Frank … I’m not sure how we’re going to get you into Europe … all that lovely money.” She crosses the Atlantic Ocean by boat and she dies by the end of the book submerged in her bathtub, leaving Malcom to answer questions surrounding her death. “What is your mother’s age? … What is your place of residence? … Was she unwell? … Have you lived apart in the past? … Did you anticipate this from your mother? … Had she been despondent recently? … And she’s been emotional? … Do you have any idea why she behaved that way?” DeWitt lives in Portland, Oregon.

Songs for the Cold of Heart by Eric Dupont, 608 pages

Songs for the Cold of Heart is about a song with a bass clef inscription: “Will you love me all the time?/Summer time, winter time./Will you love me rain or shine?/As I love you?/Will you kiss me every day?/Will you miss me when away?/Will you stay at home and play?/When I marry you?”

The story begins in 1958, in the town of Rivière-du-Loup, where Louis Lamontagne is home with his three children. The main destiny of all school-aged children in the book is to “pray pray for the salvation of their soul, give thanks to the Blessed Virgin, and take communion regularly.” In 600 pages there are a lot of stories. The daughter of Louis Lamontagne, Madeleine, is a successful restaurant owner and her two children, Gabriel and Michel, play a pivotal role in the second part of the book, translated from French and originally titled La Fiancée américaine. Dupont lives in Montreal.

Motherhood by Sheila Heti, 304 pages

You get the feeling that the protagonist has an entourage of people she knows; these people make few decisions for her partner or herself. The protagonist is contemplating her plan to have (or not have) a child with her partner Miles.

“Now my periods are getting irregular,” the narrator explains. “Even a year ago they came every twenty-eight days. Now they can be off by two days or three. It makes me sad to see this drop in my fitness to reproduce, and other things. Time is running out.”

Miles is concerned with the decision of having a child, and gives this decision to the narrator to figure out: “He doesn’t want a child apart from the one he had, quite by accident, when he was young, who lives in another country with her mother, and stays with us on holidays and half the summer.” The book asks, “Since life rarely accords to our expectations, why bother expecting anything at all?”

One of the better character dynamics in the book is the relationship between Miles and his daughter, and he plot is easy to understand, with easy to read passages. Heti lives in Toronto.

An Ocean of Minutes by Thea Lim

In Canadian culture, time travel was popularized in television before this novel in the show Being Erica (2009-11). In three seasons, the show on the CBC had the title character meet a psychotherapist in an office to access a time portal to a reverse time and place that does not affect the future.

In Thea Lim’s novel, the premise of time travel is different: The protagonist is Polly Nader, a 23-year-old Lebanese secretary at a bookkeeping firm in 1981 Buffalo, NY, who wants to work as an upholsterer. Her boyfriend, Frank, works at a bar. She is fleeing a pandemic. The title is best explained by the following passage: “Forever I promise to remember your face against that beautiful sky and sea tossing us up and down and the merry creaking of the boat and how you say, Polly I can’t unlove you.”

In the novel, it is possible to reroute to the future—it is September 4, 1998 to be precise, although Polly searches for 1993. Polly experiences time travel when an army psychologist at Houston Intercontinental Airport examines her. In her travel, she thinks she can have a baby with Frank, but in her absence Frank sleeps with a medical student named Donna and has a baby girl named Felicia. While an interesting read, the book leaves readers questioning Lim’s decision to go forward in time as an unconventional plot device. Lim lives in Toronto.