INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE IS RISING IN CANADA, WITH IMMIGRANT COMMUNITIES FACING HEIGHTENED RISKS AND SYSTEMIC BARRIERS TO SUPPORT.

Content warning for descriptions of abuse. A list of resources is included at the end of the article.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a shadowed crisis that transcends borders, cultures, and socio-economic backgrounds. In Canada, evidence suggests that IPV is on the rise, with immigrant communities bearing a disproportionate share of vulnerabilities. Understanding IPV—its dynamics, its impact, and the pathways to support—is crucial for breaking the cycle of abuse and fostering resilience.

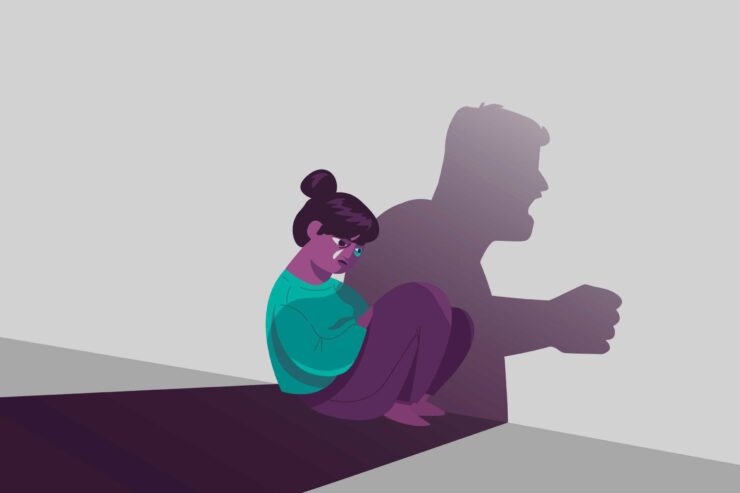

What is Intimate Partner Violence?

IPV refers to abuse or aggression that occurs in a romantic relationship. It can manifest in various forms, including physical violence, sexual violence, emotional abuse, and financial control. A study from U of O’s faculty of Health Sciences defines IPV as the “imbalanced power dynamics between intimate relationships that lead to profound psychological and physical abuse”.

Psychological coercion and gaslighting are also common tactics used by abusers to manipulate their victims, making it difficult for them to recognize or escape the abuse. Women, particularly those from marginalized backgrounds, are at an increased risk of experiencing IPV, though it can affect individuals of all genders and sexual orientations. The intersection of race, economic instability, and legal status further compounds these risks, reinforcing the necessity for tailored intervention strategies.

Dr. Patrina Duhaney, an expert in domestic violence and the intersections of victimization and criminalization, holds a PhD from Wilfrid Laurier University and has specialized in studying women who have both experienced abuse and been accused of using violence in their relationships, a subject she has extensively researched throughout her academic career.

Now as an associate professor at the University of Calgary, Duhaney emphasizes that IPV in immigrant communities is not a cultural predisposition but rather a consequence of intersecting systemic barriers. “We need to look at the ways in which race, gender, class, religion, and immigration status intersect to complicate women’s experiences,” she explains. “Rather than blaming culture, it’s important to critically examine structural inequalities, including poverty, discrimination, and limited access to services.”

The Impact of COVID-19 on IPV

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated IPV rates worldwide, with lockdown measures trapping victims with their abusers and limiting their access to support services. Evidence suggests the pandemic significantly increased IPV incidents due to heightened financial stress, social isolation, and restricted mobility.

For immigrant communities, these challenges were even more pronounced, as many faced additional barriers such as precarious legal status and reduced social networks. “If a person is arriving and they’re not really certain of their immigration status, they might be reluctant to inform the police of an abusive partner for fear of being penalized or deported,” says Duhaney. Without accessible resources and legal protections, many were forced to remain in dangerous situations.

Why Are Immigrant Communities More Vulnerable?

Several systemic and cultural factors place immigrant communities at greater risk of IPV. Language barriers, limited access to social services, and pending immigration status often compound victims’ isolation. A news report by CBC News highlights how the fear of deportation can prevent victims from seeking help, even when their lives are in danger. Moreover, cultural stigmas around divorce or family disruption can discourage survivors from coming forward.

Economic dependency is another significant factor that increases vulnerability to IPV within immigrant populations. “Many survivors feel trapped in abusive relationships because they are reliant on the primary breadwinner to provide for the entire family,” Duhaney notes. “When you have language barriers and limited recognition of foreign credentials, it forces individuals into precarious labour sectors with low wages and job insecurity, making it even harder to leave.”

The Reluctance to Declare IPV an Epidemic

In Ontario, the provincial government has faced criticism for not declaring IPV an epidemic, despite evidence of its widespread prevalence. According to The Conversation, this reluctance could have three major consequences: insufficient allocation of resources to IPV-related programs, inadequate public awareness campaigns, and continued gaps in data collection.

Duhaney argues that funding disparities further disadvantage immigrant communities. “Most domestic violence services are primarily geared towards white families,” she states. “There is a lack of intersectional approaches in these services, and many community-based organizations serving immigrant populations are underfunded, limiting their capacity to provide culturally and linguistically appropriate support.”

How to Recognize and Support Survivors

Recognizing IPV is not straightforward. Abusers often manipulate and control their partners in ways that may not leave visible scars. Friends and family members should watch for signs like frequent injuries, withdrawal from social activities, or sudden changes in financial independence. Psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, or expressions of hopelessness, may also indicate IPV.

Duhaney stresses the importance of community-driven solutions. “We need to empower communities to help others within their networks,” she says. “Community leaders, faith-based organizations, and survivor-led initiatives play a crucial role in breaking the stigma surrounding IPV.”

If you suspect someone you know is experiencing IPV, approach them with empathy and without judgment. Avoid pressuring them to take immediate action; instead, provide them with resources and reassure them that they are not alone. Organizations such as the Nelson House Women’s shelter and Interval House of Ottawa support centre can offer immediate assistance. The presence of a trusted support network can make all the difference for someone seeking to escape an abusive relationship.

Breaking the Silence

To combat IPV effectively, society must address the structural inequalities that enable it. Public awareness campaigns, legislative reforms, and adequately funded support systems are essential. Increased funding for shelters, mental health resources, and legal aid programs can provide survivors with real, actionable options for escape and recovery.

Duhaney advocates for policy changes that would protect immigrant survivors, such as expanding access to permanent residency for those fleeing abuse. “If a person is in an abusive relationship, they need to know they can leave and not lose their legal status,” she emphasizes. Additionally, she calls for increased translation services in legal and support systems and improved training for law enforcement in handling domestic violence cases.

Ultimately, IPV thrives in silence. By raising awareness, supporting survivors, and advocating for systemic change, we can work toward a future where intimate partner violence is no longer a pervasive crisis. If you or someone you know is experiencing IPV, remember that help is available, and no one has to endure abuse in silence. Seeking assistance is not just an act of survival—it is a step toward reclaiming one’s life and autonomy.

Below is a list of domestic resources:

On campus:

- Human Rights Office, 1 Stewart Street, Room 121

- Health and Wellness Centre, 801 King Edward Ave, (2nd Floor)

Off campus:

Survivor lines:

- Ottawa Victim Services: 613-238-2762

- Fem’aide: 1-877-336-2433

- Talk4Healing: 1-855-554-HEAL (4325)

- Assaulted Women’s Helpline: 1-866-863-0511

Online support:

- Unsafe at Home Ottawa: 613-704-5535

- myPlan Canada

- Supporting a survivor:

- Talking with Assault Survivors: 800-656-HOPE (4673)

- Emergency resources:

- Community resources:

- Interval House: 613-234-5181

- Planned Parenthood: 613-226-3234

- Minwaashin Lodge: 613-741-5590

- Sexual Assault Support Centre of Ottawa: 613-234-2266