CHEO-U of O research team identifies key determinants as age and sex

A study conducted by the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) and the University of Ottawa has found stark differences in concussion recovery times between adolescent male and female patients.

The authors of the study, led by U of O psychology professor Andrée-Anne Ledoux, hope to create a toolkit that care providers can use to better plan concussion recovery treatment timelines.

Concussions, as an injury, have only seen significant research in the last few years, leaving many medical professionals with conflicting information about proper treatment. The unique nature of brain injuries also means that common medical assumptions don’t apply in all situations.

“We always discuss that a child’s brain is really plastic, and since it is so plastic it can resolve problems and recover from a concussion much faster,” Ledoux explained.

“But, (in) zero to five, our pediatric cohort; this isn’t actually the case. They won’t recover faster just because they are a child.”

Ledoux went on to explain that concussions are often underreported, both in adult and young populations due to a lack of general understanding about the condition.

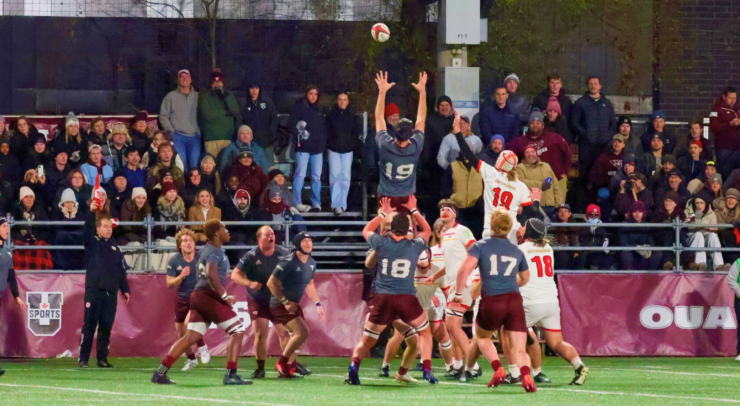

“You can get a concussion from walking into a wall, from falling down. In sports, you can get one just from being body checked, without ever hitting your head.”

Ledoux stresses that some limitations in how data for the study was gathered limits how reliably they can compare recovery times across age groups—like all studies, the public should be careful not to put too much faith in any single paper. However, the findings on pediatric recovery times are significant, and represent a break from the mainstream medical community.

Although it was not the original intention of the study to explore sex differences, Ledoux’s team discovered significant differences in recovery time between female and male patients across all under-18 age groups.

“So with all age groups, we see the most recovery in the first two weeks, but after that things start to plateau,” Ledoux said.

“At four weeks, adolescent men are mostly doing fine, but with girls we are still seeing real symptoms at that point.”

According to the study, young women still have symptoms as far as 12 weeks after the initial injury — a period in which most young men make a full recovery.

The study compiled a series of recovery curves — charts that demonstrate how quickly a patient’s symptoms will decrease. The team hopes the charts will encourage care providers to think more about the individual patient when planning their recovery.

Though research is lacking on the topic, Ledoux hopes that her team’s study will contribute to the better treatment of future patients.