Both communities express why the conflict matters to them and the importance of the region

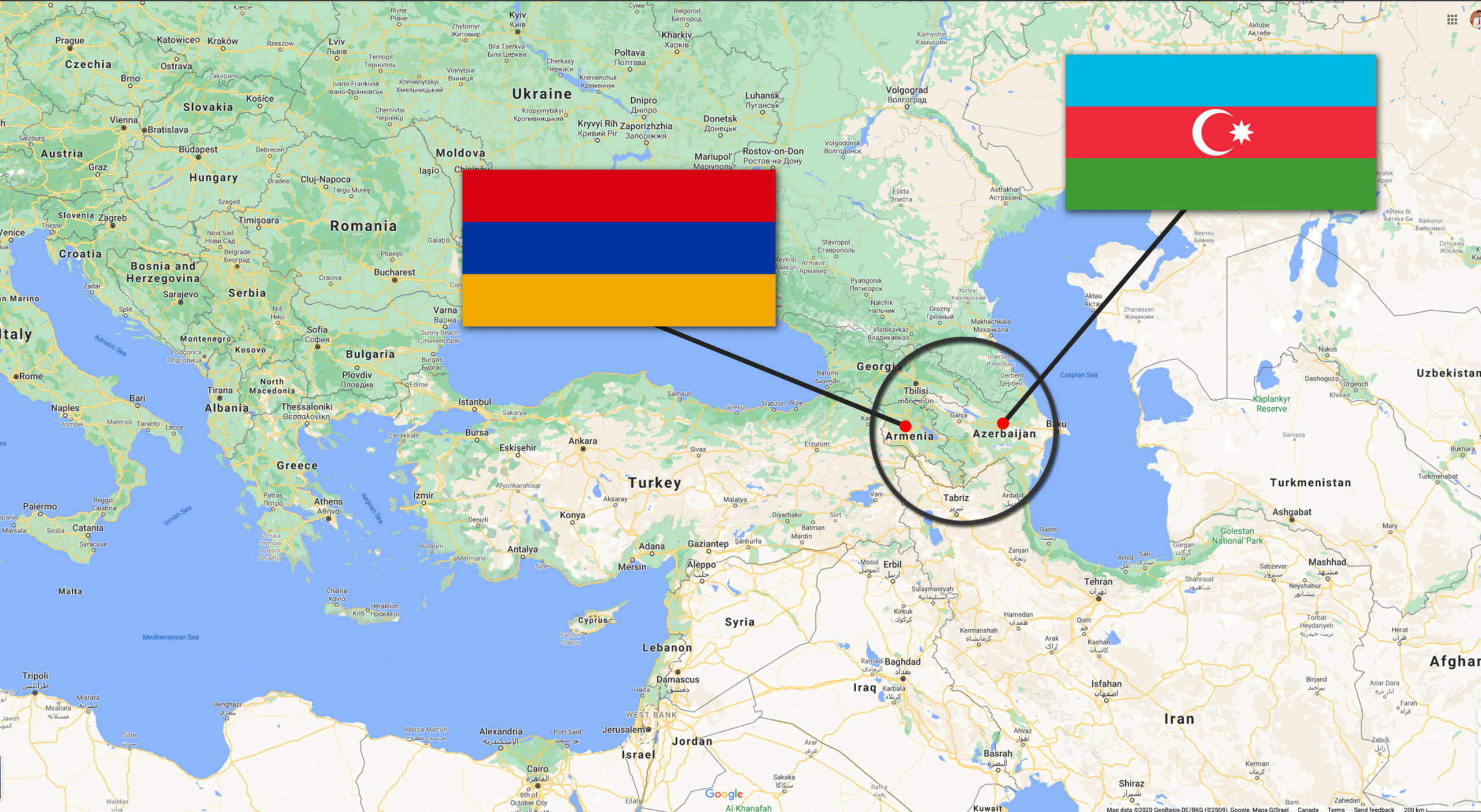

On Jul. 12 and then again on Sept. 27, Armenia and Azerbaijan, two countries located in the Caucasus region between the Black Sea and Caspian Sea, engaged in an armed conflict after several decades of quiet conflict over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh and Artsakh by Armenians.

The region which is inhabited by mostly ethnic Armenians has been at the centre of an ethnic and territorial conflict dating back to the end of the Soviet Union.

“When the people of Nagorno-Karabakh, mostly Armenians, started to demand independence from Azerbaijan and unification with Armenia that then led to a war of independence for Nagorno-Karabakh, which continued after the collapse of the Soviet Union,” said Paul Robinson, a professor of public and international affairs at the University of Ottawa.

This civil war led to over 700,000 Azerbaijanis being displaced from the region of Karabakh and Armenia, and 300,000 Armenians being displaced from Azerbaijan. Armed conflict in the region had ceased since 1994, and both countries were engaging in peace talks trying to decide the proper solution to the issue.

“The final status of this region has not been agreed upon,” said Robinson.

“Azerbaijan has a huge interest … despite whatever occurred back during the Soviet period, it is recognized as part of Azerbaijani territorial integrity,” said Robert Austin, a professor at the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto, who specializes in the Balkans and Caucasus regions.

As a result, Turkey became increasingly involved backing Azerbaijan, whereas Russia has been supporting Armenia.

While both Robinson and Austin said that Armenia originally had more power in the situation during the early 1990’s, the power dynamic has now shifted in favour of Azerbaijan.

“The narrative in both countries focuses on Karabakh and neither country ever made any effort to kind of explain the peacekeeping process or make peace a possibility,” said Austin.

Armenian diaspora

There are both Armenian and Azerbaijani diaspora communities in Canada who have been showing their support for their countries in the conflict. However, despite being thousands of kilometres away from the fighting, the conflict still impacts them in profound ways.

“This is seen as the worst possible thing for us, because we already have lost so much, not only land but people and everything else,” said Melissa Moubayed, a second-year commerce and common law student at the U of O who is of Armenian origin.

“These are ancestral Armenian lands … there are churches and monasteries dating back to the third, fourth, fifth century, that are still there today,” said Moubayed.

“It’s heartbreaking.”

“We are completely tied to those regions; we are indigenous to those lands,” said Anna, a 31-year-old Armenian woman who is opting to use an alias to protect her identity out of personal safety.

“It’s a direct threat to our heritage and our culture and it means that there is a direct attempt for genocide and ethnic cleansing … this conflict means so much more than just a conflict,” said Anna.

For many Armenians living in Canada, their grandparents and relatives lived through the Armenian genocide and were forced from their lands.

“We are survivors, we are grandchildren of survivors of the first genocide,” said Anna.

Anna’s family was forced to flee their homes in order to avoid the 1915 genocide and her grandparents subsequently became orphans; her family does not know if their last name is even their real last name.

“You’re seeing it happen in the 21st Century again,” she said.

“It’s almost as if history is repeating itself,” added Moubayed.

However, being so far from the conflict does not mean that it feels further away. Both Anna and Moubayed expressed similar feelings of hopelessness and frustration over not being able to help in more “tangible” ways.

“It’s emotionally exhausting and it’s psychologically exhausting … it’s extremely frustrating, you feel helpless, you feel hopeless, you feel frustrated,” said Anna.

“It’s definitely difficult being here … privileged and safe,” said Moubayed.

“We want to do something so all we can really do is spread awareness on our socials, protest, donate money, but nothing super tangible that we can do,” she said.

Both women also expressed frustration over the lack of media coverage of the conflict, with Moubayed saying “the amount of media that covered this was so minute compared to other conflicts, and we were able to see that.”

“It’s a wound that’s never healed, and it’s just ripped open again … you felt left alone 100 years ago, and now you feel like you’re left alone again,” said Anna.

Despite the negatives, Moubayed was moved by the “incredible amount of unity” throughout the world from the Armenian diaspora.

Azerbaijani diaspora

For Azerbaijanis, the conflict also hits close to home. One of these individuals is Farhad Hajiyev, a second-year graduate student at the University of Toronto.

Hajiyev’s wife is from Nagorno-Karabakh and as a result, lost most of her family during the conflict in the early 1990’s and the rest were forced to flee to Azerbaijan.

“The conflict is flesh and blood to my family,” said Hajiyev in an email.

The region played an important role in the Azerbaijani economy and security, and Hajiyev also noted that “Karabakh is a historical heartland of Azerbaijan.”

Anar Jahangirli, the associate director of the Network of Azerbaijani Canadians, spent time as a volunteer in camps for displaced Azerbaijanis during the conflict in the 1990’s where he would help teach lessons to children, saying the soldiers involved in the conflict are “those kids who grew up in the tents and went back to take back their homes.”

Prior to the conflict, the ethnic composition of the region was about 75 per cent ethnic Armenian and 25 per cent Azerbaijani; the 700,000 that were displaced in the original conflict made up ten per cent of the entire Azerbaijani population.

“Within the Soviet Union, there were lots of interethnic marriages and the marriages between Armenians and Azerbaijanis were seen as one of the most in numbers,” said Jahangirli.

Anna voiced a similar sentiment about relations between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, saying “I don’t believe they were bad, because it was just one union, where borders were insignificant.”

For Hajiyev, being in Canada during the conflict, brings up negative feelings.

“There was a certain sense of guilt that others were fighting and dying while I was studying here,” said Hajiyev.

“However, as a diaspora, we had a mission to raise awareness and amplify the voices of war victims,” he said.

Jahangirli notes that the Azerbaijani community is “introverted” and rarely engages in lobbying or protests.

“No one wants to come and fight those wars here,” he said.

“We really think that this is the place where we should not … go and, you know, lobby against a particular group or other country, because people don’t want to create that kind of atmosphere in Canada.”

Looking forward

On Nov. 9, Armenia and Azerbaijan signed a ceasefire agreement to end fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh. The peace deal was brokered by the Russian government, which stipulated that the Armenian forces withdraw from the region and would be replaced by Russian peacekeepers.

While both sides are happy that a ceasefire was declared because no more lives would be lost, it seems that the conflict is far from over.

For Jahangirli, the conflict is “not just about land” but rather the displaced Azerbaijanis.

“It’s about them being able to go back to their homes.”

Going forward, Moubayed hopes that Armenians around the world continue to champion the cause of Nagorno-Karabakh and continue to “raise awareness to prevent the continuation of a cultural genocide.”

“The recognition of Artsakh is the only way to assure the people living there will live in peace because this can happen again, this was not a permanent agreement. It was just a temporary solution.”