First president of a secular U of O passes away

Andrew Ikeman | Fulcrum Staff

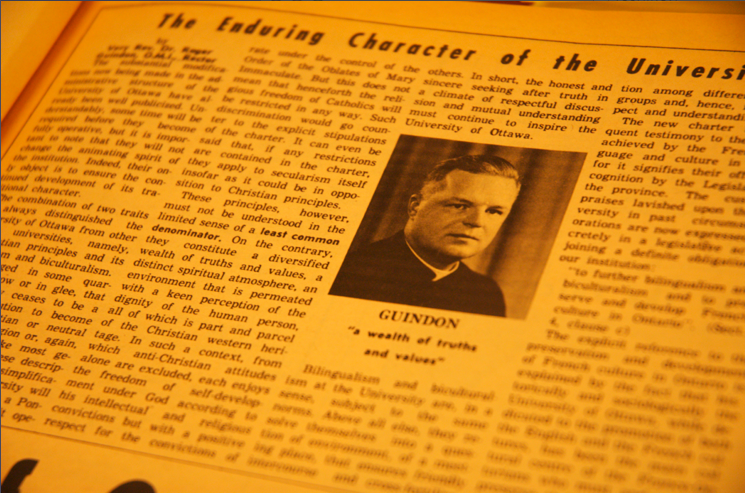

FATHER ROGER GUINDON, the president of the University of Ottawa from 1964-1984, has died at the age of 92.

Guindon began his time at the U of O in 1933 as a student, and taught in the faculty of theology from 1947-1964, during which he served as the faculty’s dean.

Allan Rock, the current president of the U of O, recognized that Father Guindon was one of the founders of the modern University of Ottawa.

“Father Guindon was a remarkable man who will be remembered with deep respect and affection for his many qualities and achievements,” read a statement by Rock. “Perhaps more than anything else, however, his name will forever be associated with the astonishing transformation he brought about at our university. Roger Guindon was nothing less than the founding father of the modern University of Ottawa. Under his remarkable leadership, a small private institution owned by the Roman Catholic Church transformed itself in 1965 into what was to become one of Canada’s leading public universities.”

Father Guindon pushed hard to establish a health sciences and medicine campus, helping to set up funding from the Ontario government for the campus on Smyth Road, which now bears his name. He was the first president of the U of O after it’s days as a church institution, helping the university move from a small Roman Catholic Church-owned private institution into a public and secular university.

“It is alleged in some quarters, in sorrow or in glee, that the university ceases to be a Catholic institution to become ‘merely’ Christian or neutral in the matter of religion, or again, purely secular,” reads a Sept. 7, 1965 column Father Guindon wrote in the Fulcrum, entitled “The enduring character of the University of Ottawa”. “Like most general judgments these descriptions are gross over-simplifications. True, the University will not further be bound by a pontifical Charter nor will it operate under the control of the Order of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. But this does not mean that henceforth the religious freedom of Catholics will be restricted in any way. Such discrimination would go counter to the explicit stipulations of the charter. It can even be said that, if any restrictions are contained in the charter, they apply to secularism itself insofar as it could be in opposition to Christian principles.”

Rock, who was the president of the Student Federation of the University of Ottawa in 1969, remembers his run-ins with Guindon in a positive light.

“In 1969, during my time as president of the University of Ottawa student association, I presented him in his office with our demands for student seats on the University’s Board of Governors and Senate—a rather radical notion at the time,” read Rock’s statement. “These steps were long overdue, I insisted, and must be taken immediately. He made it clear in no uncertain terms, though, that reform would come on his timetable, not ours. I discovered only later that Father Guindon had already begun paving the way for the changes. He simply needed the time to bring others around, and he succeeded. Within the year, student representatives were welcomed into the membership of both bodies.”

Rock said that the U of O stands as a memorial to Father Guindon’s hard work and dedication to the place he spent so many years as a student, teacher, and administrator.

“Father Guindon was a modest man and a person of deep faith,” said Rock. “He would, I know, recoil at the idea of an elaborate memorial or commemoration in his name. But in a very real sense, the University itself is the most enduring monument possible to his extraordinary work.”