Capital Pride festivities capped off in late August and the city’s eyes were captivated by rainbow flags, jubilant lip locks, and parade floats meant to symbolize solidarity in the capital. But with so much attention on the fanfare and strong sense of accomplishment that comes with Pride, comes the danger of underestimating the long road that lies ahead.

Canada legalized gay marriage in 2005, with the United States following suit in 2015 after a monumental Supreme Court ruling. While on the surface it might seem the tide has turned, and major strides have been made at a governing level in North America, there are still countless issues plaguing the LGBTQ+ community—and those issues simply cannot be ignored by the main event that catapults this community into the spotlight annually.

A 2011 study from Egale, which surveyed over 3,700 Canadian secondary students over two years, reported that 70 per cent of participating students heard sexually offensive terms used in the classroom every day, while almost 10 per cent heard homophobic comments from teachers daily or weekly.

But the problem isn’t limited to the classroom. According to a 2011 Ontario-based survey, LGBTQ+ youth are 14 times more likely to commit suicide or abuse substances, and experience higher rates of depression and anxiety than their peers. The same survey found 77 per cent of trans students had seriously considered suicide while 45 per cent had made a suicide attempt.

In Canada, trans adults and youth alike face unreasonably long wait times for transition surgery, and in Ontario they must jump through bureaucratic hoops to have the procedure covered by the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. To this day, despite the fact that gay, lesbian, and bisexual Canadians are all explicitly protected under Canada’s anti-discrimination and hate crime laws, trans Canadians are not.

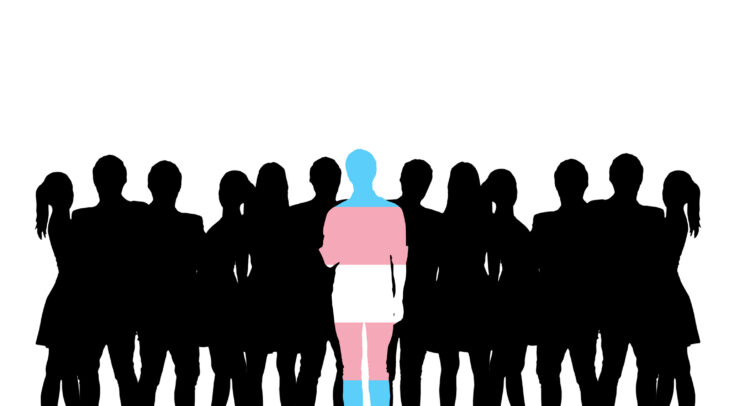

The situation is even worse for queer and trans people of colour, who are underrepresented in media portrayals of the LGBTQ+ community. They also experience greater discrimination, poverty, wage inequality, and difficulties accessing health care than white LGBTQ+ people and people of colour who are not part of the LGBTQ+ community. Queer and trans people of colour are also at a greater risk of violence and murder—this is especially true for trans women of colour.

While Capital Pride’s fashion shows, parades, and picnics are memorable ways to create a community of acceptance and celebrate how far the LGBTQ+ community has come, it’s time to start using Capital Pride’s established exposure to make more noise about these issues.

We need to demand that Capital Pride acts as a platform to lift injustice from the shadows, educate the public, and put civil rights back to the forefront of political discourse.

Civil rights movements, in essence, were predicated on formal gatherings where public leaders are questioned and held accountable for the work they’re doing to further the rights of oppressed groups. So let’s bring politics back to Capital Pride—and no, I don’t mean having Justin Trudeau march in the parade.

Capital Pride’s event schedule should include, at the very least, a roundtable with political leaders that can enact meaningful change and hear members of the LGBTQ+ community voice the issues they face that aren’t given enough attention. It’s not every day that this community has the privilege of undivided attention from political leaders in a public forum—so why not use the much larger voice of Capital Pride to demand that opportunity?

And what about Justin Trudeau? While it’s true he missed Ottawa’s Pride parade, that should be the least of our concerns. Pierre Trudeau’s infamous Bill C-150 was known for decriminalizing gay sex, but is still unconstitutionally restrictive. Why not use Justin Trudeau’s presence at modern-day Pride events to fight for the repeal of the inherently homophobic age of consent for anal sex between two men—which is two years older than the age of consent for other sexual activities?

Not only should Pride get political, but educational components are crucial to the longevity of this movement. While members of this community are united in some issues, there is so much room to learn about the experiences of each subsection—endless discussions to be had about the interaction of sexuality, racism, sexism, ableism, and much more, and how these factors impact the experience of members of this community. Pride must take an active role in scheduling events that focus on the diversity of these experiences. Change, political or otherwise, cannot come without an educated populace.

Black Lives Matter (BLM) Toronto received heavy criticism for protesting at the 2016 Toronto Pride parade, with some media outlets going so far as to equate the activist group with “bullies.” A fact that failed to make headlines or garner any sort of attention is that trans women of colour played an integral role in launching the LGBTQ+ movement, starting with the Stonewall riots.

With this context it makes a lot more sense that BLM Toronto chose Pride to raise their voices to represent LGBTQ+ people of colour and their experiences—but if this group had been given an adequate platform with Pride to educate others about those unique experiences, would this more radical approach have been necessary?

If anything, the BLM protest serves as an important lesson that Capital Pride must learn from: beneath all the cheers and celebrations, not all voices or issues in the LGBTQ+ community are heard equally—it’s time to change that, and Pride is the place to start.