RESEARCHERS WHO ARE trying to pinpoint causes for rampant cheating in high schools and universities are wasting their time.

This month, the campus newspaper at Harvard University published a summary of a survey administered to incoming first-years that asked students about their cheating habits throughout high school. According to the Harvard Crimson, almost half of survey respondents admitted to cheating on an assignment at some point.

“Ten per cent of respondents admitted to having cheated on an exam, and 17 per cent said they had cheated on a paper or a take-home assignment,” the paper reported. “An even greater percentage—42 per cent—admitted to cheating on a homework assignment or problem set.”

These statistics come less than two years after half of a 250-person class of Harvard government students was accused of cheating on the take-home final.

The news is a bit shocking, particularly for those involved in the study and administration of post-secondary education; it could be disconcerting to find out that nearly half of freshmen at a prestigious Ivy League school have cheated on their way there. But Harvard students aren’t alone, and the cheaters don’t stop once they get their acceptance letters.

The number of reported instances of cheating at the University of Ottawa has spiked in the last decade.

In 2006, University of Guelph researcher Julia Christensen Hughes conducted the first national survey of Canadian undergraduate students’ attitudes toward cheating. The survey used statistics provided by universities on reported cases of cheating.

At the U of O, the number of cases multiplied by almost eight, from 22 in 1998–99 to 180 in 2004–05. The highest rates were recorded among arts, social sciences, and engineering majors.

Statistics from Carleton University showed similar upward trends. From 2000 to 2005, the number of recorded offences in the faculty of arts and social sciences more than doubled and blew up more than tenfold in engineering. The faculty of public affairs and management was the only program in which the rates declined.

The University of Toronto makes its decisions regarding cases of cheating and plagiarism available online. The documents reveal students will go to great lengths for a good grade.

One case involved a female student who had an impersonator wear a niqab and take her midterm and final exams. The professor became suspicious when the student was found to have scored very well on the exams in a chemistry course she was otherwise failing.

Another involved a man who manipulated two girlfriends into attending his classes and writing his essays. The two women later testified against him in front of the University Tribunal. The man insisted he wrote an essay on SARS worth 25 per cent of his grade, though he was unable to tell the tribunal what the acronym stands for.

“I think what we have to teach people is that these are serious mistakes and that they really have to learn to make sure that they are attributing people’s words to the people who wrote them,” U of T professor Glen Jones, who specializes in studying higher education, told Sun News.

Jones uses the word “mistakes” rather lightly, since the issue at hand is about more than just mistakes that lead to discipline or expulsion. There are those who make mistakes but don’t get caught. The students that don’t get caught are hurting themselves almost as much as the students that do.

Christensen Hughes told the CBC in a recent article—published with the headline, “Why student cheating is rampant”—that part of the problem is that culturally, students are being sent the message that it’s important to win at all costs. She also noted that technology has made it continually easier for students to cheat on their schoolwork.

It’s easy enough to speculate on what might cause a student to cheat, but it’s only speculation. It’s unfair for researchers to try to pinpoint one or more particular causes for cheating. Yes, technology keeps changing, therefore creating new ways to cheat. But those who want to cheat will cheat, and those who don’t want to cheat probably won’t. And technology also makes it just as easy for professors to catch cheaters.

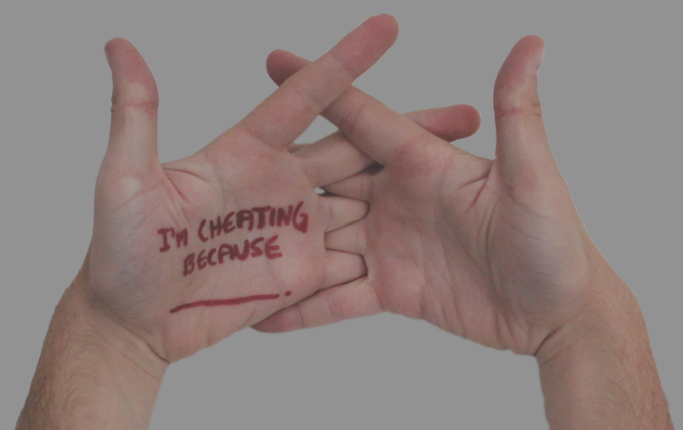

The U of O’s guidelines to help professors and examination invigilators recognize, prevent, and address cheating state that “there are many ways students may cheat during an examination” and that “their creativity in this area should not be underestimated.”

It is clear from the many crackdowns on cheating and from the numbers of reported cases—though there are surely many more that go unreported—that universities are keeping up with the cheaters, or at least attempting to. It’s imperative that they do so, because some students will cheat no matter what. It’s unnecessary to lump them all together and find a scapegoat for behaviour that’s predetermined.

There should be no article titled, “Why student cheating is rampant.” Researchers in education should not look for underlying cultural or societal attitudes that drive students to cheat. Instead, they should shift their focus to help prevent cheating and identify it when it happens.

University students are supposed to be hard workers and critical freethinkers. School administrations should treat them as such and try to weed out those who choose to take the easy way out.

editor@thefulcrum.ca