Money must be made, but hard work should never go uncredited

For the longest time, ghostwriting was the dirty little secret of the publishing industry. In the pre-Internet age, most of the general public had no idea that the work of uncredited writers was crucial to the publication of countless celebrity autobiographies and popular book series.

But these days, more and more people are starting to clue in to the practice of anonymous authorship.

The most recent example of this public unmasking came at the expense of British YouTube personality Zoe Sugg (also known as Zoella), who received a lot of flak after it was revealed that she was not the sole writer of her debut novel Girl Online.

Cases like this have provoked a mixed reaction from avid bookworms. Some like to think it’s a deceptive practice in which greedy publishers exploit a lesser-known writer by selling their hard work under a more profitable name. Others are more forgiving and believe that ghostwriting is perfectly acceptable as long as the “real” author gets paid.

I like to think that the answer to this ethical dilemma lies somewhere in the middle.

The reality of the situation is that the publishing industry is largely dependent on the hard work of uncredited writers. In an interview with NPR, literary agent Madeleine Morel outlines the necessity of this practice, estimating that up to 60 per cent of non-fiction bestsellers are ghostwritten. While big-name celebrities and political figures surely have interesting stories to tell, not all of them have the time or writing talent to present this information in a compelling way.

Coupled with the fact that many ghostwriters can make a prosperous living by publishing anonymously or under a different name (with some making hundreds of thousands of dollars per book), this collaborative process seems to benefit all parties involved.

However, there are still some elements of this process that are undeniably shady.

Not only is the idea of ghostwriting manipulative and borderline false advertising, it also comes off as being a little condescending. By holding back on the mention of an additional writing credit, publishing houses seem to communicate the idea that the act of artistic collaboration somehow diminishes the value of their product. This is a worrisome sentiment, espe- cially since most worthwhile works of art are the result of multiple contributing parties.

At the end of the day, the one deciding factor that will help mediate both points of view is that of transparency on the part of the publisher.

This means that publishing houses should go out of their way to highlight the collaborative efforts that make these books possible in the first place, while also maintaining more marketable names as top billing.

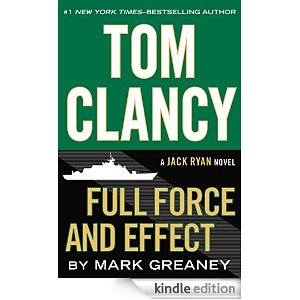

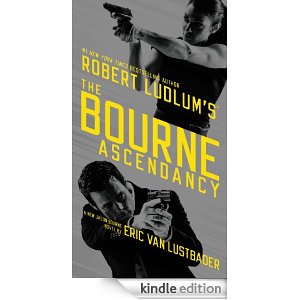

This strategy is used for the latest novels featuring Jack Ryan and Jason Bourne, two book series that prominently feature both the names of their money-making deceased authors (Tom Clancy, Robert Ludlum) and the “real” author on the cover (albeit in much smaller text).

While this policy is still partially dishonest when it comes to highlighting the level of each author’s involvement, these publishers at least manage to find a fitting compromise: maintaining financially bankable names in their marketing while also admitting to the involvement of lesser-known writers.

Hopefully in the future, more publishers behind high-profile celebrity properties will have the confidence and good sense to take a similar approach.