Canada’s Thanksgiving festivities wrapped up this past week but, as Pete Wells of the New York Times pointed out in his recent article, many of our nation’s culinary traditions on this holiday are “Americanized,” lacking an individual identity.

In the same week, Angus Reid Institute released a poll where 68 per cent of Canadian respondents said that minorities should be doing more to fit in with “mainstream” Canadian society, rather than continuing to practice their own customs and languages.

Conservative leadership candidate Kellie Leitch believes so strongly in the need for a core, mainstream identity that she is currently proposing in her campaign that a survey question should be posed to refugees and immigrants to screen for “anti-Canadian values,” and holding consultations with Canadians to determine what exactly those values should be.

Although on first glance these events may not seem related, they all point to the fact that our Canadian identity lacks any true definition. But is a vague Canadian identity, driven largely by thriving multiculturalism, really a bad thing?

To answer that question, we need precedent—luckily, there are plenty of historical events that show how forced assimilation into “Canadian culture” isn’t such a benign action.

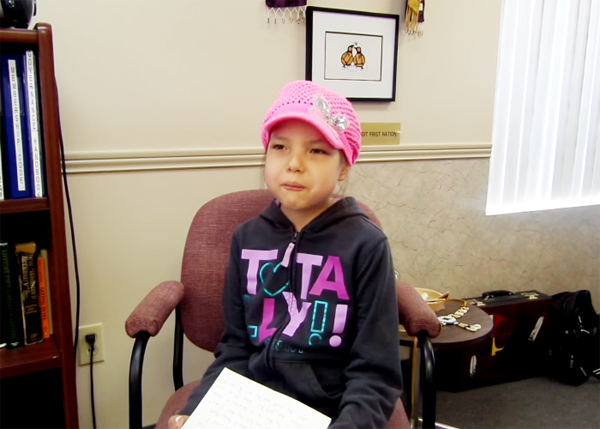

Remember Canada’s Indian Act? This 1876 legislation laid the groundwork for the longest deliberate attack on human rights of an ethnic group in Canada’s history. Its content stipulated that anyone practicing a traditional Aboriginal ceremony would be liable to imprisonment, and that traditional Indigenous governance would be replaced with federally chosen leaders, among other culturally intrusive regulations.

Residential schools were one of many negative outcomes hailing from this Act. According to accounts from Indigenous people who attended the institutions, students were constantly subject to psychological, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse at the hands of the school’s authorities—all in the name of assimilation.

Indigenous people still feel the effects of forced assimilation today—with the increased alcoholism, suicide, violence, blatant lack of urgency from the government during water crises, poor police relations, and more seen in Canada. These consequences serve as a reminder that forced assimilation leaves painful scars on any culture, and that the damage can take centuries to fully repair.

But forced assimilation doesn’t just hurt the group targeted—while not comparable to the atrocities of abuse and oppression, non-minorities in Canada would also pay a price for goals rooted in achieving a homogenous identity.

On a micro-level, our cities would be much less memorable without evident multiculturalism—could you imagine Toronto or Vancouver without the diverse urban districts that give visitors a small taste from across the globe?

On a macro-level, forthright multiculturalism is just smart business. With the massive trend towards globalization comes the necessity of mastering cultural understanding across a variety of settings. When companies can recruit Canadians originally from the countries targeted for expansion, they attain a competitive edge over culturally homogenous corporations. Forced assimilation would lead to a struggle for Canada’s business leaders to compete on a global scale, which would have an adverse effect on the economy.

Not to mention that small-to-medium-sized businesses owned by immigrants have been reported to be an effective means of linking Canada to global markets beyond the U.S. This is especially important from a trade standpoint, as Canada is currently sending approximately 75 per cent of its total exports to the U.S.—a dependency that can only be offset by accessing new global markets.

Our fashion, food, and entertainment industries also grow stronger with more global talent and cultural ties to draw from. Diversity in these sectors not only piques curiosity from native-born Canadians but can be a source of familiarity and nostalgia for immigrants, a situation which is likely to increase spending and therefore strengthen the contributions from those sectors to our economy.

So why hide our indispensable cultural heterogeneity behind a facade of “true Canadian identity?” Isn’t it a good thing that our nation is so dynamic and multifaceted that we don’t necessarily boast a set identity? Culture is a fluid concept anyway, and as it changes to suit the needs of society it often renders our beloved cultural stereotypes archaic and useless.

With these historical cautions and modern-day realities in mind, the Fulcrum stands proud of the vague identity that has come to define Canada.

Now, this may not be convenient for others who tirelessly aim to nail down a cultural stereotype for each country. But to define our culture by one small piece, without acknowledging the valuable diversity surrounding it, would be a massive disservice to our nation’s immigrants who make Canada truly worth living in.