Why recycling isn’t it

Recycling has long been regarded as the quintessential solution for waste management in Canada. However, it isn’t the simple, sustainable solution that’s been advertised.

It’s no surprise that not everything is recyclable — it’s the premise of sorting garbage. What is shocking, however, is that recycling is not all it’s cracked up to be. In fact, very few items actually are recyclable. According to a 2019 study, only nine per cent of the 305,000 tonnes of plastic that Canadians dispose of in a year is recycled. The remainder of that waste is incinerated or disposed of in landfills or natural environments.

Moreover, even materials that qualify as recyclable cannot undergo the recycling process infinitely. Unlike metals, which can be almost indefinitely repurposed, plastic, wood, and paper deteriorate and become lower-grade over time. These materials are frequently used only once or twice more before they end up in landfills.

Recycling is also an energy-intensive process, often using non-renewable energy sources while contributing to pollution and carbon emissions. We also ship a significant portion of our recyclable waste to ‘developing’ countries, leading to additional emissions produced by transportation and consequently contributing to pollution of the environments of these countries.

The recycling market

So, why is it that so little of our waste is actually recycled? The answer lies in the structure of Canada’s recycling system. Waste disposal is widely seen as a public service that is under the control of the government, but the system is far from socialized.

While the municipal government is responsible for waste collection, the actual recycling and disposal is done by private industries. This means that since the introduction of the blue box system in the early 1980s, recycling has been largely controlled by volatile commodity markets.

The strategy developed by the Canadian government was to sell our recyclables and use the profits to compensate for costs incurred by government recycling programs. However, not all recyclable materials are desirable and profit margins have always been thin.

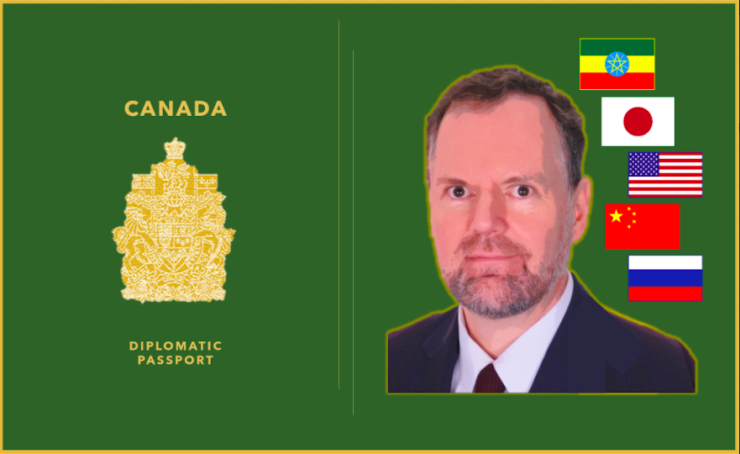

What’s more is that Canada and other ‘developed’ countries, such as the U.S. and Japan, depend on ‘developing’ countries, such as China, to purchase and process our waste. Canada ships about 12 per cent of its plastic waste outside of North America, where it often ends up in dumps or polluting local environments. Because of the cheaper labour costs and less stringent environmental laws in certain countries, Canadian waste disposal firms increase profits by exporting our waste, rather than domestically repurposing it. Since the 2018 National Sword Policy passed in China, banning many types of waste imports, the recycling market has only further been destabilized.

Due to the costs of recycling, recycled plastics are often more expensive than new plastics, making them less desirable to buyers. When the profit margin for recycling is too small, recyclable waste is often instead burned or dumped. Notably, this is because both landfills and recycling companies are owned by industry rather than government, regardless of whether it is recycled, industry profits from our waste.

Reduce, reuse, recycle

This well-known environmental slogan lists three important steps to waste management. However, in Canadian society, recycling is emphasized in lieu of its preceding counterparts. A more suitable layout is that of the waste hierarchy that stresses the importance of reducing the amount of waste that we initially create.

Our current waste management system is more beneficial to the private industry than to the environment. This is because of society’s normalization of recycling instead of reducing and reusing, harmfully incentivizing a wasteful production scheme.

By emphasizing recycling, we absolve the industry from ensuring the reduction and reuse of the items that they manufacture. The most simple, sustainable solution to waste management would be to significantly reduce our consumption. However, this would dent industry profits.

To tackle Canada’s waste problem, we must address our waste problem at its roots: overproduction and overconsumption. It isn’t enough to repurpose the heaps of waste that we produce. We need to address the systems that lead us to produce them. We need to reduce the emphasis on profit in waste management and, instead, prioritize the higher tiers of the waste hierarchy. Thus, we need to reduce, reuse, repair, and refurbish before we recycle.