Band-aid solutions are ineffective for systemic crisis

Many communities across Canada have felt the pain of suicide. Children, siblings, cousins, friends—suicide does not discriminate—or does it?

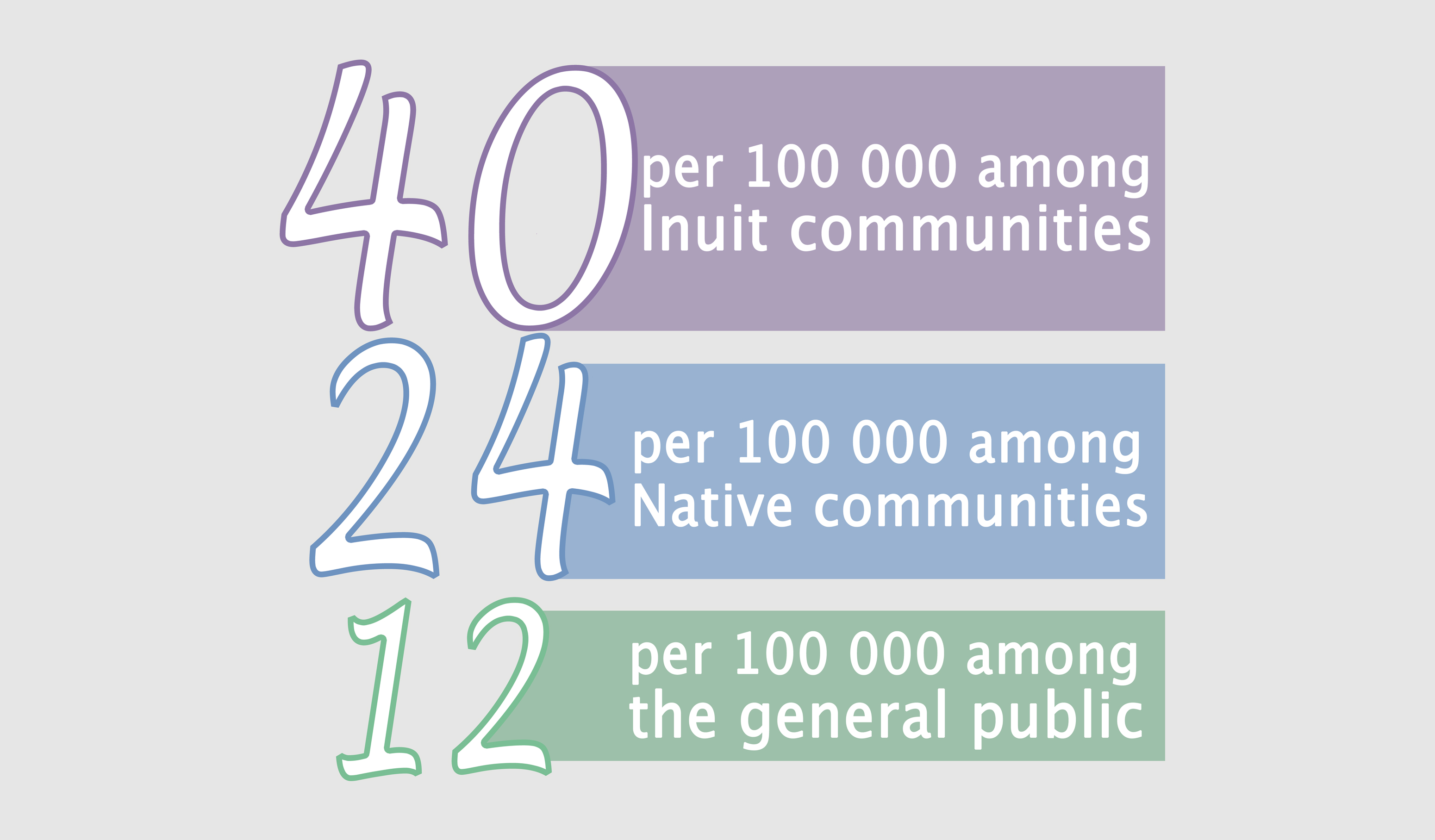

The rate of suicide amongst Canadian Indigenous youth in particular is five to six times higher than the national average, and within that group, Inuit youth have the highest at 11 times the national average.

Numerous Aboriginal communities have declared a state of emergency in the past, and the latest is the Pimicikamak Cree Nation of Cross Lake, Manitoba on March 9. The declaration captured the media’s attention rather fleetingly as it was more like old news, a shadow of past headlines that made news several years ago.

Traditional quick fixes, like counselling, don’t apply here—the government must increase their provisions in rehabilitative and social assistance, like employment opportunities, in order to improve the overall socio-economic status of Indigenous communities

Yet, the fact that suicide is still rampant in Aboriginal communities today should still be alarming, despite the promises of reform to come in mental health programs. The government’s method of assistance should be re-evaluated so that it’s geared towards providing a solid and sustainable social structure.

There are several factors that have contributed to this epidemic. Firstly, most of these communities are located in northern and remote parts of the country. Not only that, but many of these communities are fly-in.

This means that there are no roads going in and out. The only way to access the community is through an airplane, or frozen river road in the winter—that is, if the ice is thick enough.

This is why it’s also integral that the government provides greater infrastructure, such as roads, which can in turn provide enterprise opportunities with neighbouring towns.

While the permafrost up north is an obstacle to infrastructure-related projects that we wouldn’t have to face in southern or eastern Ontario, it’s worth investing in research and development and employing chemical engineers to find a solution to this long-term problem.

Furthermore, the loss of a rich culture that was stripped from the Aboriginal population through residential schools and the need to conform to the rest of Canadian society can further fuel the deterioration of one’s sense of identity. Education is also limited as many high-schools are without academic-level courses.

Without education, people are restricted in what they can do for the betterment of their community. Academic courses, which can lead to higher education, should be funded and implemented. Social and monetary assistance should be offered to students transitioning from remote to more urban areas for post-secondary education.

Although there is federal funding to provide post secondary education to First Nations, not all First Nations applicants are eligible, and many are denied funding. This denial cannot be fixed by mental health counselling alone, it can only be solved by the government honouring the First Nations’ treaty right to education.

Aboriginals are also facing the struggles of racism, and are commonly labelled with negative stereotypes relating to drug and alcohol abuse, high suicide and incarceration rates. This can simply be amended by better education for the rest of Canada.

People need to understand that these negative stereotypes are symptoms of a broken system, that is the result of the past injustices towards the Aboriginal population.

Understanding the dark history that has been inflicted upon Indigenous people is key to eliminating discrimination. As such, it is necessary that Canadian history courses emphasize this shameful aspect of our nation’s past starting at the elementary school level, rather than suppressing it in the name of national pride.

Years ago, there were programs in place to prevent suicide. There were many workshops, and counselors were sent to communities in hopes of making a positive difference. But with the current tragic state of the Pimicikamak Cree Nation prevailing over these efforts, it’s evident that such programs are only band-aid solutions to a larger underlying problem.

The government should aim to build a healthier north by providing sustainable solutions to communities—and that means enough funding for social assistance, adequate infrastructure or research to drive this project, and initiatives that bridge the gap in education.

By giving Aboriginal people these resources, Canada can create an environment where the Indigenous community can ultimately become self-sufficient, stronger, and confident in their cultural roots, and not feel like third-class citizens.