Regulated payment system would create stable supply

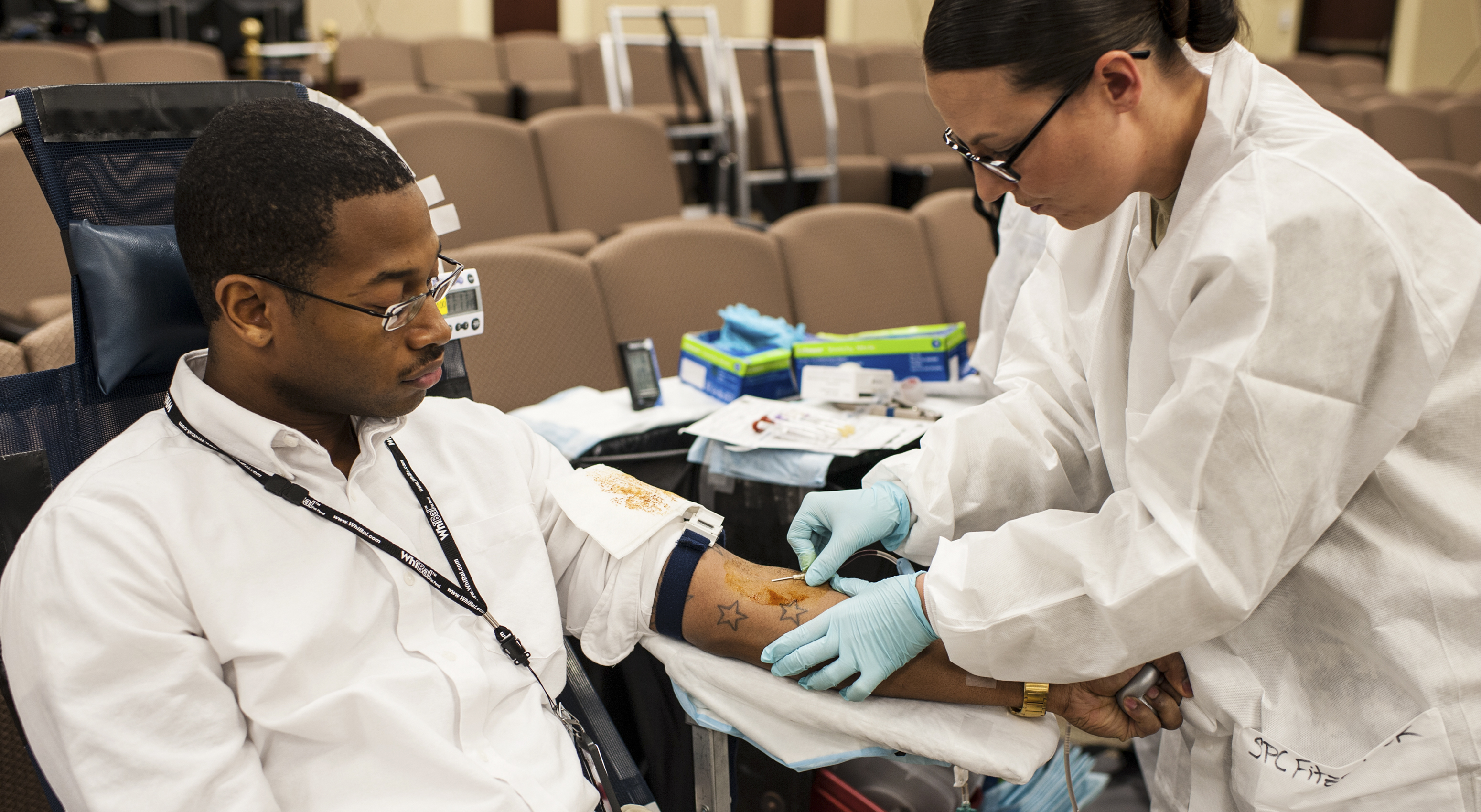

Canadian Blood Services (CBS) make several appearances each year on campus at 90U residence, collecting voluntary blood donations, like it does with the rest of its donations. But the CBS always faces the uncertainty of running out.

Currently, the CBS relies on people’s generosity to donate blood—but they’d ensure a stable supply if they paid donors.

The CBS breaks the whole blood it collects into components: red blood cells, platelets, plasma and cryoprecipitate. Blood is a precious but perishable resource, currently held for 42 days by CBS before being disposed of, making it all the more important to maintain a steady supply. That expiration date was called into question last year by a study from U of O professor Dean Fergusson, although it is still adhered to by CBS.

But if blood is held in such high esteem, why does the CBS risk shortages so often?

The CBS released multiple appeals for blood donors from June-October in 2013, and hit a six year supply low in September 2014, before advancements in the use of red blood cells in medicine allowed the CBS to reduce overall collection targets in 2015. Instead of bouncing between oversupply and frantic calls for donations, why not simply pay donors for their blood to maintain a steady supply?

The strict rules around blood donation in Canada stem from the Tainted Blood Scandal of the 1970s. Faced with a blood shortage, the Canadian Government purchased surplus blood from the United States. The blood came from a high risk prison population, and the federal government failed to use a new test for Hepatitis C meant that the tainted blood infected thousands of Canadians with HIV and Hepatitis. The CBS was created to redistribute collected blood in response to the tragedy.

Despite their best efforts and a taxpayer-funded budget of approximately $1 billion, the CBS counts 412,000 active blood donors, a donation rate in line with the developed world. However, the CBS fails to meet the Canadian demand for plasma-derived products and purchases as much as 70 per cent of their plasma stock from other countries who pay donors for blood donations. By compensating people for their blood as these other nations do, we can provide an incentive to donate more often.

A common point against blood compensation is that it will drain the voluntary donor base. However, a John Hopkins University study has found that a $5 to $10 gift card increases the likelihood of donating by 26 per cent and 46 per cent, respectively, and even increased rates of voluntary donations. Who cares if voluntary blood donations decrease? The purpose of the CBS is to maintain a safe blood supply for Canadians, not to ensure people donate for moral reasons.

Other arguments claim that payment for blood will allow collection agencies to coerce marginalized people into selling their blood. As a government mandated agency, the CBS can regulate the system to make sure this doesn’t happen.

The CBS has taken a hard line against compensating donors, despite its many clear benefits.

Academics, professionals and even Health Canada have found no evidence that compensating blood donors produces negative effects. With so much at stake, perhaps it is time to revisit this debate to create a long-term sustainable blood supply for Canadians from Canadians. After all, I could always use $20 in my pocket!