Jumping for joy over these spiders

Sebastian Echeverri always knew he loved animals, but he never thought that working with them was a possibility for people who looked like him. Throughout his career at the University of Pittsburgh, his excitement for animal research led him to study jumping spiders and in doing so, challenged his ideas of what a spider could be.

This week, the Fulcrum sat down with Sebastian Echeverri to discuss his PhD research on how paradise jumping spiders communicate with their signature courtship dance.

What are paradise jumping spiders?

According to Echeverri, Habronattus pyrrithrix (fiery-haired jumping spiders) are very small. The typical size is approximately one centimetre, and the males are smaller than the females. Adult males can be identified by their bright red face, bright orange knees located on their third leg, and green hairs under their arms, unlike the females, who are mostly brown. These spiders are found throughout the American Southwest and in Northern Mexico, often in grassy areas.

Within this genus of spiders, there are over 120 species, which all have their own dance, colours, and approach to courtship.

What is their courtship dance?

Echeverri describes their courtship as a musical show, which includes both a song and dance that are coordinated together. Like any good show, they build tension throughout and leave the best performance for last.

To begin, the male will lock eyes with the female and lower his pedipalps to reveal his brilliant red coloured face. His dance begins by waving his arms up and down as he slowly approaches the female. Now he must be incredibly careful when approaching, because he is smaller than the female and is at risk of being attacked or eaten by her.

Once the male is close enough, the real courtship can commence. He will lock into place and lift his first leg straight up into the air and then tip his legs. The movement is similar to a wrist flick and will form a U-shape by moving both legs together. Then he covers up his red face with his pedipalps so that only his eyes are exposed. The male will then vibrate his abdomen against the ground to create the song part of the musical, which will change in pitch and speed at different points throughout the dance. As the song continues, he will slowly mimic a knee pop motion where he ratchets the third leg pair into the frame made by the first pair of legs. He’ll show off his knees, one after the other.

In the third part of the dance, the spider will transform his entire body shape by moving his third pair of legs over his shoulder and right above his head. In doing so, he will create an orange hexagonal display over himself. His legs that were previously making the wrist flick motion will now begin to move at an incredibly fast rate above the female’s head. Nearing the end of this courtship, the male will then attempt to mate.

For those interested, the entire courtship dance can be seen here.

PhD research: part one

The first part of his research focused on understanding what the females were paying attention to and how often they see the males’ colours. According to Echeverri, while male jumping spiders have vibrant colouring and the dance seems to rely on his colours, only two of six image forming eyes can actually see colour, meaning that their field of view changes dramatically depending on what they’re looking at.

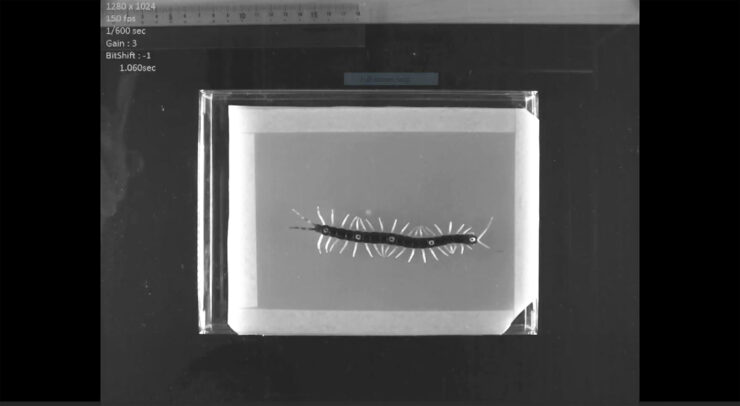

“First, we put the spiders on a flat arena, and we filmed them from above. And we basically looked at where they were facing throughout their entire dance. Since the lenses of their eyes are part of their exoskeleton. Unlike our eyes, the actual eyeball cannot rotate. So they’re basically kind of locked in place,” said Echeverri.

He added, “so we basically could tell from where the spider was facing. What part of its field of view could be seen in colour, which is basically a 60 degree cone in front of their head and then everything else is in black and white. By filming courtship and pulling that footage out, and every fifth of a second we pulled a still frame.”

At every interval, he calculates what angles the males and females are facing, which part is in the males and females field of view, can the female see the males colours, etc. Throughout the entire dance on average 70 per cent of the time the male is visible only in black and white because the female is not staring directly at him.

He continued, “that changes our idea of what matters. If these colours are really the most important thing, why isn’t the spider always watching them? Now, if most of the time he can’t actually show off his red face because she’s not actually watching. Then there’s a new problem that males have to solve, which is how do I get her to look at me?”

PhD research: part two

That new problem for males leads into the second part of Echeverri’s PhD research, which focused on the different aspects of the male’s dance and what helps him attract the female’s attention. The part Echeverri focused on was the start of the dance, when the male is doing these big arm waving displays. It’s the first interaction that the two animals have and it’s where we know that the colour red is the most important. It’s what females use to make a decision on allowing the male to approach.

In essence, “I played videos of these spiders to the females. And I asked her, which one of these do you think is more interesting? And then that has a lot of follow up questions of how? And the answer is that I glued a little magnet on the top of the female’s head, and I suspended her in front of two computer monitors and I gave her basically a little foam ball to hold as if it were the ground.”

He added, “then I played two animations on those computer monitors. One of them was a male that was not waving, he was just in his courtship position. And then the other one was a male that was waving his arms, but at different sizes of the movement and different speeds. And then I asked the female, which of these two do you think is more interesting?”

“Whenever a spider thinks something’s interesting to them, they will spin their whole bodies to stare at it directly with the two biggest eyes and that’s basically their signal. Since they see with their peripheral vision with the four eyes in the corners of their head,” said Echeverri.

What he found was that the males that did wave were more successful in gaining the female’s attention over those that didn’t. Most interestingly, when put against a distracting background and environment the males had to respond by moving closer to the females. Similar to how humans move closer to each other in a room that’s louder to get our message across. What these male demonstrate is the ability to change their behaviour to be better at communicating.

Final takeaways

Echeverri stressed the importance of challenging yourself to imagine how other people and animals experience the world. Our brains are hardwired to assume that the way that humans see things is universal, the way that we look at something and what stands out to us is what “matters” objectively.

“Everything that we know, from all the research that we’ve done, says that is false. If we ever want to understand where another person’s coming from, or why this animal is doing this thing that to us seems ridiculous. We first need to accept that those behaviours very rarely evolved for human consumption. Without thinking about the animal that’s the receiver we won’t ever really know what’s going on.”

For more information about Echeverri, you can visit his website here.