As the U of O continuously fails to adequately accommodate disabled students, those most vulnerable to COVID-19 resign to giving up on schooling – or worse – altogether.

October 2024 greets us differently than the past few autumns have. The now-campus reminds me of my first year; bundled-up ants go from one class to the next, little drinks in hand. The U of O is booming with fresh faces; naked and unmasked.

My classmates’ sniffles are just allergies, or so they say. And my professors hack and cough and nearly project their souls out because of a minor cold, or so they say. My roommate has been intensely feverish for a week, but that’s just the aftermath of midterms… so they say.

“Calm-mongering” – a term I found while scrolling through the Reddit r/ZeroCovidCommunity – is a call-to-action tactic promoting safety, security, and wellness that is often based on wishful thinking and dubious reassurances. In the case of the largely-discarded, back-burner pandemic, calm-mongering techniques beg us to consider any and all COVID-esque symptoms as something else.

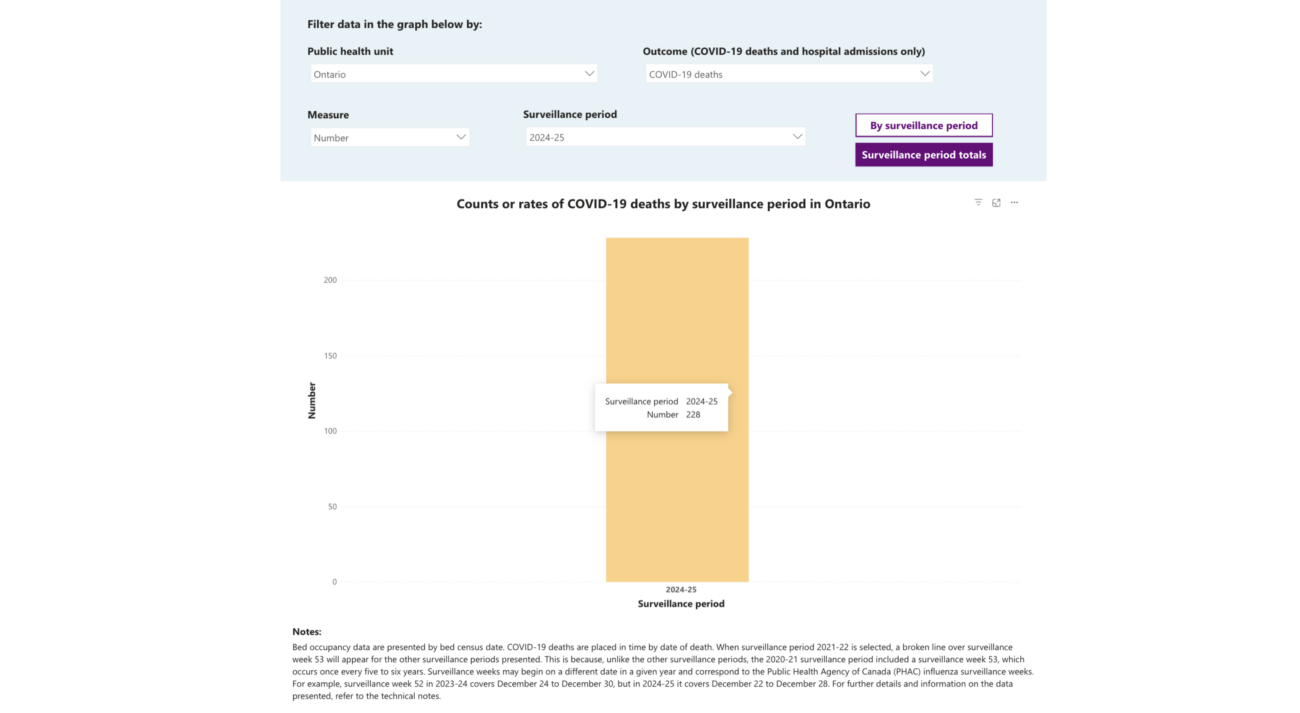

The world is, although never as it once was, back to some form of normal. Vaccines have supposedly done their job, and, according to Public Health Ontario, COVID-19 cases are projected to go on the decline between Oct. 20 and Nov. 2. Fast-forward to the end of surveillance week 47 on November 23, and only 228 people have died this year due to the coronavirus.

Ottawa’s latest COVID-19 outbreak was on Oct. 10, on the third floor of the Greystone Village Retirement Home’s Bruyère Hospital Unit. The outbreak ended on Oct. 23. Based on the data provided by the City of Ottawa, it is unknown as to how many patients, healthcare workers, and loved-ones alike were affected. Despite the case being recorded merely a week from writing this, COVID-19 is passé, historical.

On-campus mask dispensers, wall-mounted sanitizers, and physical distancing signages have become dust-collector decor. They linger in hallways. Visual pollution.

If October 2024 welcomes most with pumpkin patches and midterm exams, it reminds disabled and immunocompromised students that their education, community, and overall care are conditional. They are reminded, time and again, that some “allies” are ready to drop them when allyship becomes a chore.

Coordinator for the Centre for Students with Disabilities (CSD) Willow Robinson’s (who uses she/they pronouns) position entirely depends on them being an active student at the university, recounts feeling uneasy at the prospect of returning to in-person activities back in 2022. And she wasn’t the only one.

The reopening of full-time, on-campus activities started back in Fall 2022, leaving concerned students and staff to turn to social media to voice their frustrations. New technologies brought to the classroom by the lockdown benefited all students, and yet, those same advancements dwindled out of use. Disabled students, caretakers, and other high-risk individuals were quick to point out their loss of accommodations.

The University of Ottawa’s Student Union (UOSU) later published a statement on July 18, 2023, expressing “support for students with disabilities who are facing challenges due to the ongoing reduction of virtual and hybrid class options.” Robinson, who had also been the coordinator for CSD at the time, was not consulted regarding the statement in any way.

“I was hired for my experience to be a voice for the disabled community,” Robinson recalls, “but the previous people who were above me did not take that seriously [nor] take anything that I had to say seriously.”

The UOSU’s statement did little to sway the U of O from its push for hypernormalisation. Most classes today are strictly in-person, forcing able-bodied and disabled students alike to attend in spite of their health statuses. Even if these same students manage to get accommodation requests through Students’ Accommodation Services (as either temporarily or permanently disabled), it is ultimately up to students to self-advocate and for professors to approve of those needs.

“So if you have an accommodation to record lectures, but [the professor] doesn’t want lectures recorded, that does not matter. It is a legal right to have that lecture recorded. Now, if [they don’t] want the recording disseminated, that’s fine.” Robinson says. “However, there needs to be some kind of trust. [If not] we wait a year and a half to get complaints filed [through lawyers].”

The alternative then, would be to get into the few 280-some undergraduate virtual courses instead of having to risk having a bad experience with a professor. Of course, 280 courses means nothing compared to the total of 1,724 course codes active for Fall 2024.

For Robinson, an immunocompromised manual wheelchair-user who unfortunately needs specific classes in order to graduate, attending class could mean making their very last trip outside. “I have three courses left to finish my degree in the winter semester. So I’m going in with my giant N100 mask; the one used for cleaning up dead bodies. [It’s] a half mask that suctions to your face and bruises because it hurts so much.”

Robinson continues. “So I have to wear those, get down to campus, meet three professors, and then go home and decontaminate and then hope to every god that ever existed, I don’t get COVID from that one trip. Because if I get COVID, I will die.”

Robinson hopes that their professors will be kind enough to let them take in-person classes virtually. Other students, Robinson mentions, have opted to transfer to another university entirely. As of September 2024, Robinson and their colleagues at the CSD have helped a little over 150 students transfer out of the U of O due to poor accessibility measures.

As an unconfirmed response to the outcry, the Human Rights Office on campus shared its new initiative “uOaccessible” to the student body via email: “The University of Ottawa is committed to respecting the dignity and independence of all members of its support and teaching staff, its students and visitors” and ensuring that “persons with a disability truly enjoy free and unhindered access to University programs, services, facilities, housing and employment opportunities.”

Whether or not uOaccessible proves helpful to students is yet to be seen. Robinson, who is coincidentally also a part of this new initiative, says that they and the members of this new advisory board “can only offer so much advice, and it’s up to the University whether or not they actually take it. They rarely if ever do take the advice.”

Generally exasperated with the ways in which the U of O has treated disabled students thus far, Robinson pointed the Fulcrum in the direction of an organization that has proven to support disabled and COVID-conscious folks.

The Donate A Mask program, organized by Evidence-Based Social Enterprises Canada (EBSECan), was first established in January 2021 as a response to the developing pandemic. The volunteer-run charity continues to advocate for clean air and accessible respiratory protection through a donation shop and a free supplies service.

They offer packs of N95 masks to anyone who might want or need them and, until October 2024, also enabled people to get access to free COVID rapid tests – a health assessment tool that’s growing harder and harder to acquire.

Still, despite the general populace roaming around unmasked, volunteer Gina Bernard says that “[Donate A Mask has] given away more pieces of respiratory protective equipment in the first nine months of 2024, than we did in all of 2023. So we’re seeing a stable, if not growing, demand over the last couple of years.”

A big part of those interests have come, unsurprisingly, from disabled and immunocompromised people. Bernard notes that, out of all of the groups using their services, about 60 per cent of requests come from people with disabilities and health conditions. Other vulnerable demographics such as persons with low income, LGBTQ folks, and the elderly are also frequent customers. That said, most requesting free N95s fit within multiple marginalized groups.

Bernard extends her and her team’s care to those who are still COVID-conscious in 2024. “The volunteer capacity we have is passionate, but we always could appreciate more support. Groups like ours who are still working in the space for COVID advocacy, clean air advocacy — it’s kind of a shrinking and shrinking group in some ways, but those that are still here still care very much, and are doing really great work.”

Unfortunately, large-scale masking, both in Ottawa and on campus, is unlikely to happen again despite the COVID Hazard Index forecast marking every one in 28 people across Ontario to be infected between Nov. 9 and 22.

For the safety of immunocompromised and disabled students, Robinson looks to the new staff of the UOSU. “What makes stories like this difficult is we want to blame UOSU for all the trauma that they put on the disabled community. [But] because of the transient nature of UOSU it is difficult to place blame or get any accountability. So it’s a matter of like, okay, here’s all the new people coming in. Gods, [disabled students] hope that one of them cares. Just one. I just need one.”