Where Crazy Rich Asians fails, To All the Boys succeeds

This summer was a blockbuster milestone for the East and Southeast Asian diasporic community. In the span of just three days, two major films came out starring East and Southeast Asian-American leads.

Here’s why I didn’t see one of them but watched the other three times in a row.

Passed: Crazy Rich Asians

There seem to be two reactions in the community; those who love it and those who don’t. Those who love it mark Crazy Rich Asians as a milestone in the film industry. It has been 25 years since The Joy Luck Club, the last film with an all East Asian-American cast, was made. This means that a whole generation went without seeing their stories on the big screen—I didn’t even hear about the Joy Luck Club until my first-year English lit class where I was inevitably deemed the expert on it.

But here are five reasons why I am not a fan of the film everyone else is praising:

1) In the film, Awkwafina performs and behaves in African American Vernacular English (AAVE). She performs as the sassy best friend, profiting off Black culture as a caricature of it. However, as people of colour, we should not be endorsing problematic representations such as these.

2) Henry Golding, the male lead in the movie, is biracial (of British and Malaysian descent from the Iban Indigenous tribe). The issue with this situation is that there is a history of colourism in Hollywood where mixed faces are prioritized over full East and Southeast Asian ones. From Vanessa Hudgens of High School Musical to Shay Mitchell of Pretty Little Liars, biracial actors and actresses have continuously been favoured for major roles over other candidates who are solely of East or Southeast Asian descent.

3) The film is set in Singapore, which is home to a minority Malay and Indian populations (along with many others), but Crazy Rich Asians revolves around the dominant population of Chinese Singaporeans and doesn’t represent any of the experiences of minorities. Chinese Singaporeans are privileged in Singapore, so showing them as lead actors does not challenge or accurately depict Singaporean society.

4) There is a lot of confusion about the intention behind the film. Was it made to represent the western diasporic community or the Singaporean one? The story follows East Asian-American Rachel Chu who enters her fiancé’s lush lifestyle in Singapore, but most of the main actors that are cast to play locals are also East and Southeast Asian-American. Singaporeans have also spoken out about the authenticity of the movie and its lack of Singlish, the spoken creole language.

5) A lot of the mantra in the East and Southeast Asian American community is about pressuring us to watch and attend the film in order to increase ticket box numbers and show Hollywood that this matters to us.For example, Wong Fu Productions, one of the original East Asian-American channels on YouTube, has been pressuring its followers to buy tickets. “While this isn’t (sic) the only steps happening for Asns it is a huge one for us to take, let’s not squander it,” they tell their followers on Instagram. This method is a very performative act of allyship from Wong Fu, a male-dominated company that has only done very minimal, vanilla acts of East Asian-American activism in the past. This attitude also puts the onus on consumer activism to be responsible for change.

A lot of people who see this criticism say we can’t have it all and that this is just one step in the right direction—the burden shouldn’t be placed on just one movie. But I say do better. Why go halfway and dip your toes into the water if you’re going to do it at all?

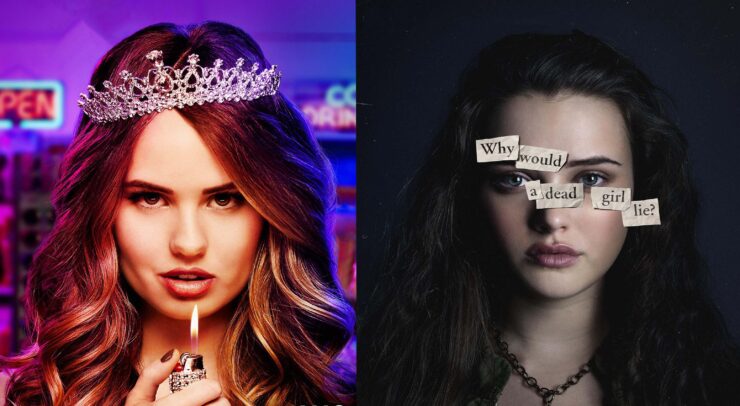

Praised: To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before

Even though To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before did not have half as much publicity as Crazy Rich Asians, it still managed to steal my heart. So, here’s where I think To All the Boys succeeded where the other failed:

1) The movie does a lot when it comes to representation. The cast and storyline of the movie give voice to the Korean, Vietnamese and Chinese communities as well as adoptees, mixed families and relationships.

2) Lana Condor, playing Lara Jean Covey, is the first representation of the East and Southeast Asian-American community to play the lead of a teen rom-com. She is a normal girl living a normal life (so normal she nearly got whitewashed) with an Asian face.

3) The film also broaches the subject of slut shaming and the role that social media plays to spread it. In the movie, Lara Jean Covey shares an intimate moment with her boyfriend in a hot tub that is filmed and posted to Instagram. But the movie suggests that Condor’s boyfriend knows of the video that instigates the accusations but does nothing to stop it initially. The film therefore offers a real-life glimpse of the fallout that can happen when slut shaming is allowed to take place.

4) The film brings up the subject of race on occasion, including a brief mention of the racist character of Long Duk Dong in Sixteen Candles to show how far the film industry has come. But the big racial challenge that came as a surprise was with the strikingly one-dimensional portrayals of the character of Chris, Lara Jean’s best friend, and Gen, the arch-rival. Unlike in most movies where the East Asian-American girl plays the sidekick to the main character without any character development, this movie delegates those roles to the non-Asian characters—Chris is the quirky friend who likes EDM concerts and Gen plays a typical queen bee and former friend.

But that isn’t to say the film isn’t without its flaws. In a Yakult cameo, Lara Jean’s boyfriend tries the Korean drink and gives it his approval. This type of gesture poses a problem, though, because exchanges like this one portray a desire for acceptance from an imagined authority in white power structures.

Like many rom-coms, there are also a lot of stereotypical gender roles. Lara Jean’s character, for instance, is predominantly shy throughout the movie, while the male lead is outgoing and boisterous.

That being said, I fell in love with the movie because I’m a hopeless romantic. but there are still problematic issues to tackle with the film. So let’s push for more—Let’s not only showcase heteronormative relationships and let’s not only show white queer relationships. Let’s do more.