The Fulcrum explores Ottawa’s history with the macabre and examines how it fits into the city’s cultural zeitgeist

Illustration: Kim Wiens

Despite being Canada’s capital and fourth-largest city, Ottawa is often considered the place where things like culture and excitement go to die.

Ask anybody from out of town what they think of this sprawling metropolis, and they’ll probably tell you that Ottawa is a dull government town full of nothing but drab buildings and sanitized historical sites.

This sort of mentality has been largely internalized by the city’s citizens as well. Back in the 1960s, local journalist Allan Fotheringham dubbed the nation’s capital “the town that fun forgot” and this label has stuck with Ottawans ever since.

Even today it seems that the city can’t shake this dubious reputation, having recently been made a subject of mockery by comedian John Oliver and a locally produced documentary short.

But beneath this seemingly placid surface there lies as much more sinister veneer.

If you look in the right places, you’ll find that “the town that fun forgot” is actually home to its fair share of ghastly ghost stories and haunted hot spots that are anything but boring.

In fact, this gripping paranormal element is intrinsically linked with Ottawa’s history, so much so that it is almost impossible to talk about one without mentioning the other.

Ghoulish and grey

Students from the University of Ottawa don’t have to travel very far to see this spooky symbiotic relationship in action.

According to Michel Prévost—the university’s chief archivist—tales of the paranormal are directly tied to some of the school’s biggest historical landmarks and figures.

For example, in a story that he refers to as “the ghost of the old lady of Tabaret Hall”, Prévost recounts how the U of O’s most prestigious building burned to the ground in 1903, an unfortunate event that claimed the lives of three people, including an elderly maid.

Tabaret Hall burning on December 2, 1903. Photo: courtesy of University of Ottawa Archives.

“She was doing the cleaning here and instead of going outside she took the wrong way,” he said. “So she passed away, and I don’t understand why, but they never found her skeleton or anything.”

Without a proper burial, the soul of this woman allegedly wandered the halls of Tabaret when it was rebuilt in 1905.

“At this time the offices were rooms for students, and many students told us that they saw this old woman during the night.”

The sightings of this spirit came to a halt once Tabaret was converted into an office administrative building in 1965, reveals Prévost. Whether this spirit finally found peace or is still wandering the halls of this building at night is anyone’s guess.

However, the U of O’s link to the paranormal doesn’t stop there. In fact, these supernatural elements can be traced back to the founding of this school in the mid-nineteenth century.

Joseph-Bruno Guigues was the first catholic bishop of Bytown, and founded the College of Bytown, the future University of Ottawa, in 1848. According to Prévost, Guigues’ attachment to the school was more than simply administrative in nature.

“He was very proud of his college. He was looking carefully throughout the development of his college. So there is a close link between Guigues and the College of Bytown.”

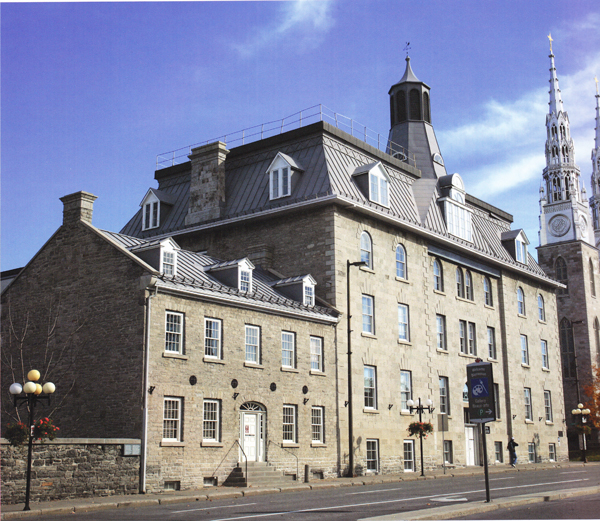

Guigues’ bond with the school he founded was so strong that he didn’t want to leave it, even after his death in 1874. According to eyewitness testimony, his spirit can still be found hanging out on the top floor of the building that housed the Second College of Bytown on 373 Sussex drive.

The building that housed the Second College of Bytown. Photo: courtesy of University of Ottawa Archives.

“It’s very amazing because (he appears) at the same hour, always the same day,” said Prévost. “And it’s one time a year. It’s the last day of the year at the last hour.”

With his roots in academia, Prévost remains skeptical of the legitimacy of these stories, since they are generally based on oral accounts. However, he is more than happy to talk about these creepy yarns with any student who is willing to listen.

“Most of our students, because we speak about ghosts, they will know that Joseph-Bruno Guigues is the builder of the university. So in that way I find it interesting because it’s a way to learn a little bit about our history.”

Ottawa’s dark past

The university isn’t the only part of Ottawa with a supernatural side. As it turns out, the rest of the city is full of dark secrets waiting to be told.

Nobody knows this better than recent U of O graduate Vincent Sabourin, who works hard to shed some light on the creepier parts of Ottawa’s past through his work as a guide for the Haunted Walk.

After working for this organization for two years, Sabourin is now privy to the idea that paranormal stories surround some of Ottawa’s most prominent cultural touchstones, including the Château Laurier, city hall, and the Canadian Museum of Nature.

However, Sabourin finds that the eerie events at the famous Ottawa Jail Hostel still produce the strongest reactions from people. This is mostly because of the site’s infamous reputation for inflicting inhumane treatment on its inhabitants during its stint as a real prison from 1862 to 1972.

Ottawa Jail Hostel. Photo: CC, SimonP.

“When you go inside the jail it’s kind of guttural. You actually hear a first-hand account of (the hangings) and people are like ‘Oh, this is how people lived? This is disgusting’.”

The former jail’s most high-profile tenant is Patrick J. Whelan, who was executed in 1869 for assassinating Thomas D’Arcy McGee.

Some historians believe that Whelan was wrongly accused of the crime, and he still haunts death row to terrify future generations for the legal and judicial failings of the past.

Sabourin’s co-workers are all too familiar with this claim.

“We used to have sleepovers in the hostel. We would all sleep in cell number four on death row,” he said. “The story goes that (my co-worker) couldn’t sleep one night… and the only way he could find peace and quiet was if he changed cells, so he went to the next cell over.”

“And the next day they we’re like ‘Where were you?’ and he was like ‘Oh, I couldn’t stay in that cell. Someone was hovering above me, telling me to go’.”

While a lot of tourists don’t normally associate these kinds of dark, gritty tales with Ottawa heritage sites, Caroline Couture-Gillgrass—who is the communications manager for Ottawa Tourism—believes that this grimy element is inescapable because it’s etched into the city’s foundation.

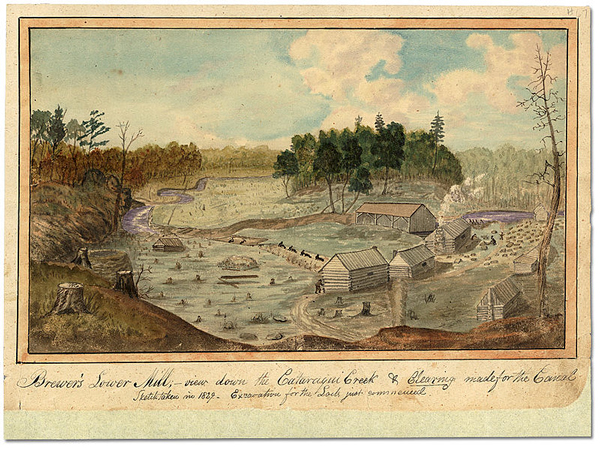

Gillgrass notes that the story behind the construction of the Rideau Canal (a structure upon which the municipality of Bytown was founded in 1826) is littered with misery and misfortune.

Rideau Canal construction circa 1829. Photo: CC, Thomas Burrowes, Archives of Ontario.

“It was built by a bunch of immigrants and many of them died while building it,” she said, noting that some historians estimate that the body count was in the hundreds, if not thousands.

“There was a lot of malaria, it was a big bog, it was uncomfortable, there were tons of brawls. ”

Unfortunately, these bodies have refused to stay buried, now that the Bytown Museum (located next to the channel locks on the Rideau Canal) is said to be haunted by these past canal workers.

Bytown Musuem. Photo: CC, D. Gordon E. Robertson.

Like Prévost, Sabourin finds that these stories serve a greater purpose than to simply dish out shallow seasonal scares.

“A lot of people don’t know that Ottawa or Bytown was known as the most dangerous city in Canada at one point. And it’s just really interesting to think about it that way because it’s a side of history that you don’t know and (these stories) are a gateway to that hidden secret of Ottawa.”

Scaring away the apathy

Of course, it’s easy for skeptics and non-believers to brush off these macabre stories altogether, believing them to be superstitious nonsense peddled to gullible idiots.

As the founder and lead investigator of Ottawa Paranormal Research and Investigations, John Moore is no stranger to this kind of attitude. However, he claims that people in the nation’s capital are particularly dismissive of the paranormal.

“The one thing I do find with Ottawa… a lot of people don’t like to talk about it,” he said. “I’ve gone down to Kingston and I find people in Kingston they’ll be more open to speak about the paranormal activity that goes on everywhere.”

In his experience, said Moore, this mentality is symptomatic of the safe, sanitized social environment that many Ottawans have taken to heart.

“It’s a government town. A lot of people work in the government or work in the political sector and they’re more concerned about (their preferences for the paranormal being known) and having some backlash from their employers.”

But even skeptics like Prévost recognize that you don’t need to believe in ghosts to get the most value out of this kind of hair-raising history. He attests to the idea that these narratives act as a great way to shake people out of their collective apathy and to get them to care about their local culture and community.

“I know because last year I organized a tour… about ghosts,” he said, describing how he took a group of U of O students on a tour of haunted sites like the Bytown Museum and the Château Laurier.

“When I’m doing (normal) historical tours I only have a few students. But (this time) I was so surprised. A lot of students came to my ghost tour and I was so surprised to see that so many students were interested.”

This same kind of enthusiasm for local horror stories was made clear in September, with the backlash that resulted when the Jail Hostel announced that it would be putting an end to its relationship with the Haunted Walk tours. However, the company behind the hostel reversed its decision six days later, a turn of events that Ottawa city councillor Mathieu Fleury partly attributes to the passionate reactions of local citizens who have “had such great experiences over the years with Haunted Walks.”

Fleury goes even further, saying that this widespread embrace of the weird and macabre is emblematic of a city that is ready to break out of its shell.

“I think it really compliments what’s happening across the city. It’s a complete change from being simply a government town to what we are today: a capital city.”

“You can see the bigger city kind of feel with the light rail, with Lansdowne, and other things that are coming into play. And when you see local arts and culture scenes, including the Haunted Walks and even the Jail Hostel, really being part of it, it just supplements the experience.”

More than just cheap scares

With Halloween being right around the corner, it looks like Ottawans are getting ready to fully embrace the creepier side of their city.

While Moore says that, in his experience, the season doesn’t have any effect on the amount of local paranormal activity, he reveals that the amount of claims of paranormal activity he receives go through the roof.

“It might be just because people are watching horror movies. It’s in their head. It’s the power of suggestion. Your subconscious starts to make things up and you see it.”

Meanwhile, Sabourin states that October is definitely the most profitable and active time of year for the Haunted Walk, with many people calling in as early as August to secure tickets for their special Halloween tours.

Hopefully these people take away more from these experiences than just cheap scares. By embracing the creepy and the paranormal, they’ll be taking part in a tradition that is as much a part of Ottawa’s culture as political double -talk and Beavertails.