Plaques on campus and at St. Joseph’s church omit details of brutal colonialism

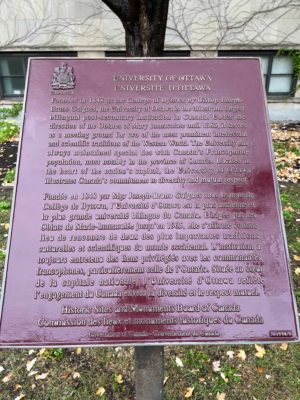

Outside Simard Hall on the University of Ottawa campus stands a plaque: “Founded in 1848 as the College of Bytowne by Bishop Joseph-Bruno Guigues, the University of Ottawa is the oldest and largest bilingual post-secondary institution in Canada,” it reads. “Under the direction of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate until 1965, it serves as a meeting ground for two of the most prominent intellectual and scientific traditions of the Western World.”

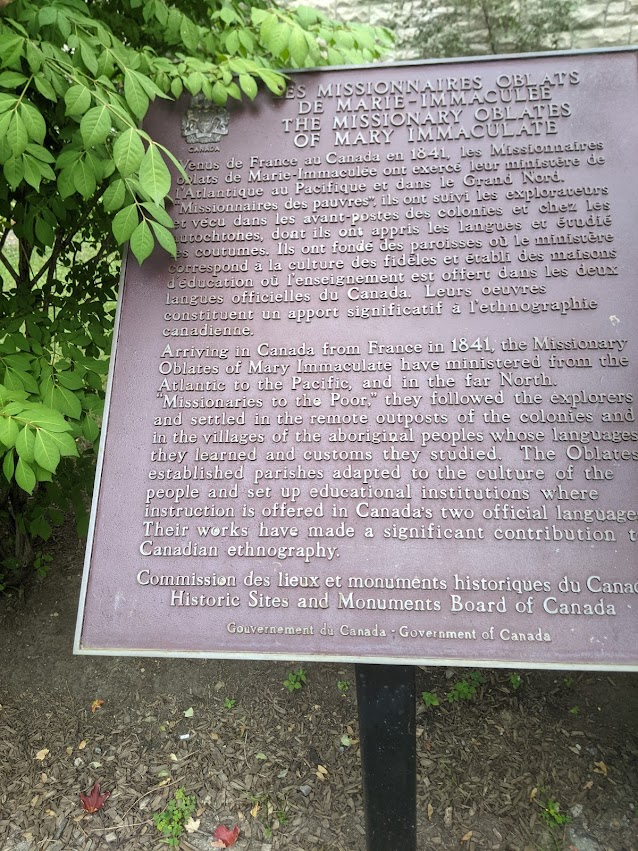

Just across the street from campus, on the grounds of St. Joseph’s church on Cumberland Street, a sister plaque stands.

“‘Missionaries to the Poor,’ [the Oblates] followed the explorers and settled in the remote outposts of the colonies and in the villages of the aboriginal [sic] peoples whose languages they learned and customs they studied,” it reads.

The plaque continues: “The Oblates established parishes adapted to the culture of the people and set up educational institutions where instruction is offered in Canada’s two official languages. Their works have made a significant contribution to Canadian ethnography.”

The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate ran up to 47 per cent of Canadian residential schools. The organization recently found itself in national headlines due to its initial refusal to release records regarding their former residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia, where the remains of 215 children were found in May. They have since agreed to comply.

Recent events like these have brought the troubling histories of institutions like the Oblates to the forefront of mainstream Canadian discourse, providing a valuable opportunity to discuss the histories we curate, whose voices tell them, and how they factor into meaningful reconciliation.

‘It’s tough to get to reconciliation without truth’

Brenda Macdougall is the academic delegate for Indigenous engagement at the Indigenous Resource Centre (IRC) and a professor in the faculty of arts at the U of O. She also works on the Indigenization file with the provost’s office. While the plaques aren’t a flashpoint for her, she recognizes their problematic nature.

“I think that the plaques are part of the ongoing conversation that Canada is having about how we memorialize and how we remember and how we educate. And if those signs, plaques, monuments, symbols aren’t actually educating, then I think that we have to question their long-term relevance,” said Macdougall in an interview with the Fulcrum.

The narrative that the plaques represent omits key facts about the Oblates. The plaque located in front of Simard Hall serves to acknowledge the University’s historical association with the Oblates. However, it completely ignores the role that the religious organization played in the residential school system. The plaque located off-campus, however, paints a revisionist picture of the Oblates as benevolent explorers.

Darren Sutherland is a U of O alum who now works for the University’s Indigenous Affairs office as Indigenous community engagement officer and works to recruit Indigenous students with the Aboriginal Post Secondary Information Program (APSIP). He is also of Cree heritage and is the son of residential school survivors.

Sutherland thinks these monuments require a nuanced treatment that prioritizes the input of survivors without erasing the history of the institutions they represent. It’s a task that Sutherland said demands more transparency and better contextualization.

“In this era of Truth and Reconciliation, it’s tough to get to reconciliation without truth. And I think that applies not just to the church, but to any organization or institution that had played some part in the settlement of this country and the things that they did in order to meet those goals,” said Sutherland.

Teaching truth

The issue of what to do with monuments illustrating Canada’s colonial past is one that has sparked heated debate over recent years. Daniel Rück, an associate professor in the department of history at the U of O, agrees that the creation of monuments like these entails the careful and intentional crafting of a historical narrative.

While he acknowledges that every historical document cannot be expected to tell every side of the story, Rück thinks the medium of the message is an important factor.

“A plaque is expensive. A plaque takes a lot of planning, a plaque is meant to be permanent. I think we have to look at the materiality of this. It’s supposed to last a really long time. So when someone writes something, they’re doing it really carefully for a plaque,” said Rück, who is cross-appointed to the Institute of Indigenous Research Studies.

“But who got to talk? Who gets to have their story on the plaque? And who doesn’t have to get to have their story on the plaque? I see it very much in terms of that [the] story isn’t complete, but it is exactly the story that those people who put the plaque together wanted to tell.”

Rück argued monuments such as these serve as evidence of a racist history in this country that should not be forgotten or glossed over, complicating the issue of removal. He believes the future of such monuments should lay with the Indigenous people they affect.

According to Macdougall, the question is what the community stands to gain from any proposed solution. Like Rück, while Macdougall sees advocating for the removal of the plaques as a viable option, it wouldn’t be her first choice.

“The University of Ottawa could certainly advocate for their removal if they chose to. But I also think that a counter-narrative can be created, and so rather than seeing them as something to remove, the question is, how do we actually contextualize better the content surrounding them?”

Macdougall suggested alternative ways to rectify the messaging. She says the university could offer a history course focusing on the history of the U of O institution and the Oblates’ organization, or a counter-plaque initiative.

“[Monuments] are not history, they are just memorials to something,” she said. “My perspective is, if you can’t tell me what it is memorializing or who those people [or institutions] are that we’re we’re concerned about — if we take the issue of the tearing down of the MacDonald statues, if you can’t tell me anything about John A. MacDonald — then you don’t know your history, and no statue is going to make that happen.”

Reckoning with a dark past

During the week of Sept. 30, a second plaque was installed next to the government plaque at St. Joseph’s that aimed to provide this crucial contextualization. This plaque, pictured above, was discovered on Oct. 1 and removed seven days after its installation.

Father Ken Thorson, the provincial leader of the Oblates of OMI Lacombe Canada, wrote in a statement to the Fulcrum that the new plaque contained a number of historical inaccuracies.

The plaque suggests that the Oblates worked in “at least 57” residential schools nationwide. It lists some of the more notable schools, including the one in Kamloops, B.C. The plaque also noted the documented reluctance of the Oblates to divulge records pertaining to the residential schools that it administered, and took special note of the role these records play in the discovery and identification of children buried at those institutions.

Thorson wrote that “the recently added plaque, while rightly referencing the involvement of the Oblates in the Indian Residential School (IRS) system, contained imprecise information.”

“The Oblates worked in 48 schools, not ‘at least 57;’ the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) had access to our archives during the course of the inquiry and over 40,000 documents are housed in the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR); we are actively collaborating with the NCTR to ensure that all remaining relevant documents will be available through the NCTR; in BC and Alberta, all of the Oblate archives from those provinces were gifted to the Royal BC Museum and the Provincial Archives of Alberta; no archives have been moved outside of Canada to prevent access.”

Thorson did not mention his organization’s initial refusal to disclose records earlier this year. He did make it clear that the Oblates are in support of efforts to publicly address their role in the residential school system. While the Oblates issued a public apology in 1991, Thorson recognizes that their work towards reconciliation is ongoing.

“The original plaque was erected by a government agency – and so they determined its content. Given our involvement in the running of the IRS, and as part of our commitment to respond to the Calls to Action of the TRC, as well as our commitment to work towards reconciliation and healing, we would welcome some kind of acknowledgement of our role in the schools, and the harm they brought to Indigenous children and communities,” wrote Thorson.

While the organization itself appears not to have plans to add any contextualizing monuments, Thorson said they would be in support of any government initiatives that aim to do so, and added that Indigenous consultation would be an integral part of this process.

The Oblates’ archival staff have been working alongside the NTRC to make their records available to the public. It’s an initiative that Thorson sees as a crucial part of their work towards healing.

“Presently, the most important contribution the Oblates can make is to the search for truth,” he wrote.

The future of the plaques and others like them

“National historic designations commemorate all aspects of Canada’s history, both positive and negative. Designations can recall moments of greatness and triumph or cause us to contemplate some of the tragic and challenging moments that helped define the Canada of today,” wrote Rola Salem, a spokesperson from Parks Canada, in a statement to the Fulcrum.

Parks Canada, the government agency responsible for commemorative plaques, has undertaken a number of initiatives in recent years to work towards a broader, more inclusive representation of Canadian history.

In particular, the establishment of the Framework for History and Commemoration, introduced in 2019, seeks to incorporate a more diverse set of perspectives — and tell a more complex story — than has historically been the case in the past.

“The Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (HSMBC), [which advises the federal government with regards to the National Program of Historical Commemoration,] also recognizes the shifts in historical understanding that have occurred over the past century and acknowledges the need to be responsive to these shifts. A process is underway to identify priorities and develop a sustainable schedule for the review of existing designations and their plaque texts,” wrote Salem.

“A broad range of existing designations are potentially controversial, have outdated reasons for national historic significance, and do not reflect contemporary knowledge and scholarship. These designations require review.”

The process can be slow-moving, as they take place according to the availability of time and resources, but Salem told the Fulcrum reviewing the Oblates designation as a National Historical Event by the Government of Canada and the HSMBC is a priority.

Salem indicated reviews might alter the justification of the designation to better recognize contemporary understandings of a historical event, person, or place. They also may result in the alteration of the story told by the plaque itself.

Like the Oblates, Parks Canada wrote that they are committed to including Indigenous voices when they revisit monuments like these.

“Similar to the processes in place for the nomination and designation process, a review of a designation will involve consultation and engagement with stakeholders, Indigenous communities, and a wide range of experts,” wrote Salem.

Consultation with Indigenous communities has led in recent years to the designation of the residential school system as a National Historical Event, and the designation of four former schools as National Historic Sites.

Looking forward

Sutherland added that the creation of the Indigenous Affairs office and the implementation of the Indigenous Action Plan (IAP) illustrate an effort on behalf of the University to find ways to improve the experience on campus for Indigenous staff, students, and faculty. He finds the growth in terms of resources for Indigenous students that he has witnessed since his time as a student at the U of O encouraging.

He said the introduction of the Indigenous Affairs office provides Indigenous students and prospective students with crucial representation.

“I think it allows [Indigenous] communities to have more trust and confidence in a university like the University of Ottawa, because I think they know that there are Indigenous people here, and some of us are in positions to really influence policy here,” said Sutherland.

Sutherland said he’s seen a lot of changes already since his time as a student.

“I’ve been here, as a student, as an employee, and even before I was a student here, my mother was good friends with one of the few Indigenous faculty members at the time, and I used to visit the campus with her,” he said.

As a child on campus, Sutherland said the only resources for Indigenous students that he can recall were the few Indigenous faculty and a much smaller Indigenous Resource Centre.

“Now there’s an office, staffed by Indigenous people, that works on policy and procedure that will improve the experience of Indigenous students, staff and faculty. An office that puts on events to try to improve the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people here on campus and raises awareness. And there’s a lot more support.”

For Sutherland, a lifelong relationship to campus has afforded him a unique opportunity to watch Indigenous presence on campus grow.

“Actually, I’m fairly certain, the office I’m in right now, I’m pretty sure this used to be one of those offices I used to visit, and now it’s the home to the office of Indigenous Affairs and the new Indigenous Resource Center. It’s actually kind of wild, in like 10 or 11 years, I went from just being a spectator or guest on campus, to working here and being part of the change that’s going on.”

Indigenizing curricula, creating more spaces for Indigenous students, and enacting structural changes within the university’s staffing and administration are just some aspects of the IAP that Indigenous Affairs is pursuing. Making aesthetic and symbolic changes is another.

For monuments like the plaques, while he would like to see more context and transparency, Sutherland also feels that his wishes are not the ones that should be given priority.

“I think this is definitely something that only a person who went through it can say. I’m not defending the Indian residential school system. I’m not defending the decisions to run those schools on the part of the church, whether it’s the Catholic or Anglican Church, whatever. But it is very nuanced,” he said.

“It’s a little complex. You obviously want to say something angry, or you want to shout and demand some sort of change,” he added. “But at the same time, I had to be sensitive about the experiences of my family, and other survivors and their families, and the continuing sort of influence it has in their lives and has had throughout their lives.”