In the wake of falling oil prices, can Canadians rely on Fort McMurray as a steady source of jobs and income?

Illustration by Adam Gibbard

When my parents told me they were moving to Fort McMurray, Alta. about a year and a half ago, I was more than a little taken aback. After all, we had lived in North Bay, Ont. for most of my adolescence and I always figured they would just retire there after my brother and I went off to university.

But, after they sat us down and explained the situation, it all made sense. If my dad worked at a mining equipment company in Fort McMurray for just five years he could effectively cut his retirement time in half, and the two of them could have enough cash left over to finally buy that house on Trout Lake they had always wanted.

I actually started to get a little excited at the idea of visiting them. Not only would I get to see them in their new digs, but I would also get the opportunity to visit the hub of Canada’s energy sector, and see what it was like for myself.

Up until that point, I had mostly learned about Fort McMurray through the filter of the media or from word of mouth. Many people likened this high-profile municipality to a modern day frontier town: a rough and tumble place that would seem right at home in an old-school Hollywood western.

When I finally got to visit Fort McMurray this past Thanksgiving weekend, I found that several of the city’s characteristics—namely its picturesque geographic isolation and infectious “gold rush” atmosphere—backed up that claim.

But more than anything, I found Fort McMurray to be a town full of dramatic inconsistencies.

Poorly built roads and condemned condominiums were a particular eyesore during our initial drive into town, especially contrasted against the beautiful new $258-million airport my brother and I arrived at. I had a similarly jarring experience when our family went to see a movie at Fort McMurray’s only theatre. Even though my parents had spent all day showing us local engineering marvels like the gigantic community centre and the brand new sports stadium, the theatre itself had the size and comfort of a shoebox. And although the area is full of gorgeous forestry and running trails, it was really hard to get past the sight of the oil sands themselves, which kind of look like the pride lands in The Lion King after Scar took over.

All and all, it was still a great weekend, but the town’s blatant lack of uniformity stuck with me well past the plane ride back.

In fairness, this kind of uneven development may just be growing pains—the symptom of living in a community that is so intrinsically tied to the booming oil industry. But now that oil prices are plummeting, Fort McMurray’s image of financial invincibility might be on the rocks—and with it may be thousands of prospective job opportunities for Canadian students.

Land of opportunity

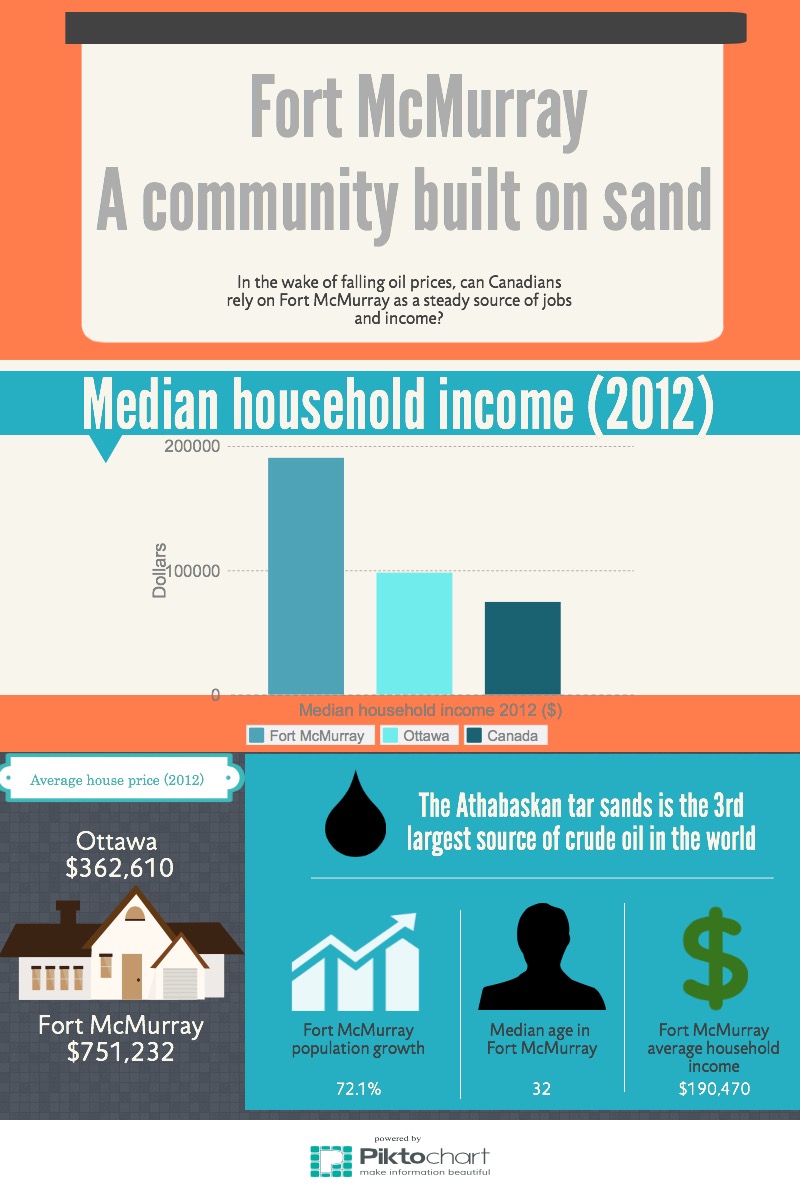

Of course, the main reason why this Alberta city attracts thousands upon thousands of Canadians like my parents every year is because it has been framed as a guaranteed source of jobs and wealth. And why not? Because of their close proximity to the oil sands, the residents of the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo have managed to carve out a prosperous living for themselves. According to the area’s 2012 census, the median household income for a local resident is $190,470, more than twice that of the average Canadian.

This economic narrative has attracted the attention of multitudes of young people, especially fresh university graduates looking to find steady employment early in their careers.

Sam Gough, a recent communications graduate from the University of Ottawa, cast herself into this migrating horde. Gough arrived in Fort McMurray in October 2014, deciding to live there after months of failing to find reliable post-graduate employment in Ontario.

“I couldn’t get a job where I was making salary,” Gough says, now working two jobs at a local restaurant and at Service Canada. “I’m still not doing what I went to school for, but at least I have a full-time job and I can use that to transfer back home eventually.”

This image of financial reliability has been shaken as of late, since the price of oil has been on a steady decline since June. As of this writing, the price of oil is hovering around $49 per barrel, significantly down from its triple digit value last spring.

The effect on Fort McMurray has been dramatic. Not only have new projects relating to the oil sands been halted, many of the contract workers have up and left. Fort McMurray’s reputation as a bastion for job-hungry students has also been compromised, with engineering graduates reeling from an unprecedented lack of job opportunities. This economic downturn has even transcended beyond the oil industry, and is influencing people’s day-to-day lives.

“(The price of oil) isn’t just affecting people who are working on the oil, but the whole town is suffering,” Gough says. “Nobody wants to go out for dinner. Nobody wants to spend their money and go to the movies. People are just being… cautious.”

However, as many industry experts have already pointed out, Fort McMurray has been in this situation before, having successfully bounced back from crippling oil recessions in 2008 and in the 1980s.

Andrew Leach, an associate professor at the Alberta School of Business, says he remains skeptical of the doom and gloom rhetoric surrounding the future of the Wood Buffalo community.

“McMurray is really the centre of the most mature part of the oil sands industry,” he says. “That town is much more reliant on the operating of (companies like) Suncor, Syncrude, CNRL, Shell, Kearl, all of those projects, than it is entirely on the construction of new projects.”

This kind of analysis still doesn’t provide much comfort for residents like Gough, who is uneasy about the coming months.

Shadows over Fort Mac

The recent economic downturn highlights another overriding concern about Fort McMurray: its apparent lack of a strong, tightly knit community.

This conversation largely centres around Fort McMurray’s “shadow population”—a group of around 40,000 workers who fly in to the community for a couple of months of work and fly out when their jobs are done. Some might suggest that a town populated largely by temporary workers does not encourage the growth of a healthy communal atmosphere, especially now that many of these workers have abandoned the city in search of more fruitful opportunities.

As a relatively new member of Fort McMurray, Gough echoes these concerns. She says many of the people she knows aren’t really taken with the idea of sticking around for too long.

“People are only working up here,” she says. “People book vacations to get away from here … Nobody stays around when they have time off.”

But some maintain that the local community is perfectly capable of promoting growth and expansion. Scott Schellenberg, a colleague of my dad’s at SMS Equipment, has lived in Fort McMurray with his family for almost 15 years and is in no hurry to move anytime soon.

“It’s a fantastic family community and that’s something that the press never seems to get right,” he says. “In the neighbourhood that I live, my son … can run out the front door and ride his bike and disappear out of sight and I don’t have to worry.”

Furthermore, Schellenberg says he believes the reduced oil sands activity will only improve their current situation, since this downtime will allow the community to develop at a normal pace.

“(We) never have been able to catch up to the infrastructure. The growth has well outpaced their ability to build to suit the infrastructure of the population,” he says. “Times like this are fantastic, where you can just let your road infrastructure catch up, and the housing prices kind of normalize a little bit.”

Ethical tug of war

Outside of these internal concerns, Fort McMurray’s well-being is also threatened by outside dissenters who object to the ethical nature of its number one money maker: the oil sands.

With the increasing frequency of divestment movements on university campuses and heavily critical celebrities like Neil Young, the fossil fuel industry has been receiving a beating in the media—which could affect the community’s economic viability in the future.

Joan Haysom, a senior researcher and manager of solar projects at the U of O, says she considers the current hubbub over oil prices to be insignificant in the long run. Energy sources like wind and solar offer up considerable benefits to fossil fuels and are even starting to hit grid-competitive prices, she says.

“The oil industry is going to be a boom-bust industry that’s dependent on global political aspects, like on wars, on decisions of foreign countries made in times of crisis,” says Haysom.

“It’s extremely volatile, compared to other industries that can be a much more stable source of energy and a healthy source of economic growth for our country.”

Schellenberg doesn’t see it as cut and dry as that. He says that, at least for the time being, fossil fuels are a necessity in our society.

“The oil sands are here for the long term,” he says. “In our generation, and probably in the generation to come, my suspicion is that we’re still going to need an awful lot of oil and these guys will be around to produce it.”

Missing from the day-to-day news reports, he says, is the progress that has been made in terms of the industry’s environmental policy. Syncrude Canada Limited, one of Fort McMurray’s biggest employers, has been particularly vocal about their reclamation projects. According to the oil producer’s website, more than 3,400 hectares of land have been successfully reclaimed in the Wood Buffalo area. One of these reclamation sites even includes a wood bison range—a welcome sight after my dreary drive through the oil sands.

Still, the effectiveness of these projects has received, to put it generously, mixed reactions from scientists and environmentalists. Schellenberg says that’s OK.

“It’s good to have watchdogs and it’s good to have people pushing back on these guys because it does make them better and it holds them accountable. There’s nothing wrong with that.”

However, now that the use of renewable energy in Canada is on the rise ,and bad press surrounding fossil fuels is never in short supply, it might not be wise for the residents of Fort McMurray to put all their eggs in one basket.

Modern day manifest destiny

I’d say uncertainty is probably the best way to define Fort McMurray. For relatively new residents like Gough, the area’s fluctuating economic prospects prompt second thoughts about staying for the long term.

“I would like to move somewhere else. I don’t want to be here forever,” says Gough. “My plan is probably to stick it out for like a year, and just get the experience and then move on.”

As for my own parents, while they do have a distinct exit strategy in mind, anything could happen between now and five years from now. My brother hinted recently that he’s interested in finding a job in Fort McMurray after he graduates from Queen’s, which could throw a monkey wrench into that whole plan.

Having said that, this sense of unpredictability is what sparked my interest in Fort McMurray in the first place. Here’s a community that’s populated by people who have uprooted their lives to try their luck at “making it big” in a western town that’s 435 kilometres away from another major urban centre.

This kind of modern manifest destiny has led to the creation of a community that’s simultaneously modern and archaic, a fascinating conundrum that has become the centre of a national discussion on economics, urban development, and environmentalism. However, like many experiments, there is always a distinct possibility of failure.

Just like the sun always sets in the West, the sun might be setting on Fort McMurray’s status as modern day boom town. Although, only time will tell.