In an attempt to make the streets of Ottawa safer, homelessness has become increasingly criminalized. However, is the link between the homeless and street crimes real, or imagined?

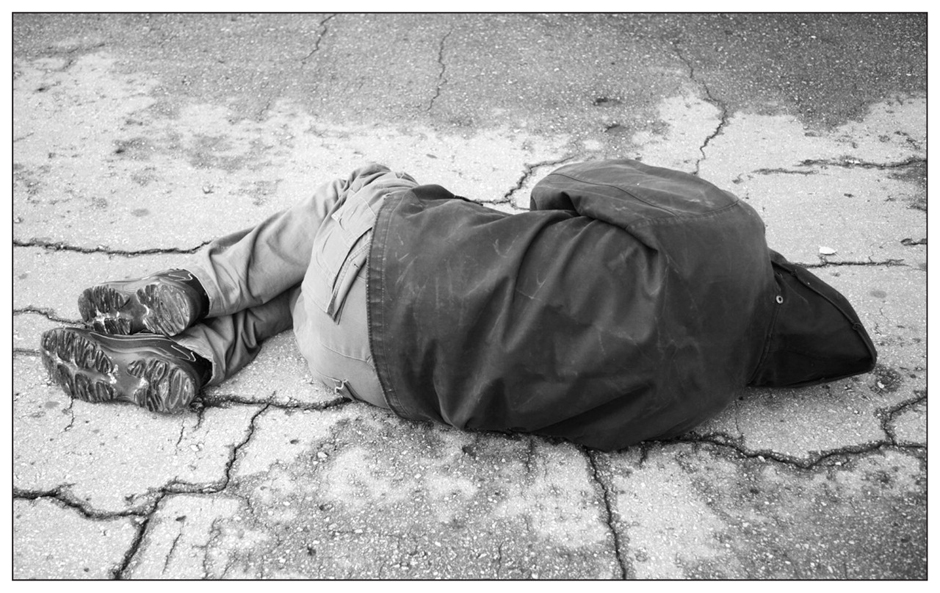

Photos by Jim Fischer and Pedro Ribeiro Simões (cc)

“Have two people jaywalk, one in a suit and one looking homeless—who do you think the cop would stop?”

By 16, Raphaëlle Ferland was homeless, a fact that makes her graduation from law school at the University of Ottawa this past spring all the more remarkable. It’s a success story few others are able to share, and she seems to know it. Despite her recent accomplishments, Ferland’s view of police and the criminal justice system has been marred by earlier experiences.

“Those who are there to serve and protect are the ones who hurt the homeless community,” she said. “They know those who are homeless and target them.”

Now 25 years old and articling at the Hale Criminal Law Office, Ferland hopes her work as a criminal defence lawyer will help her “even out at least the injustices.”

She isn’t alone in her concern about the levels of youth crime and vagrancy in Ottawa. There’s much controversy around community safety and justice, and there’s never an easy answer. Many would welcome the idea of policing the city’s most troubled neighbourhoods, regardless of the long-term consequences. But in trying to protect the public, are we making street youth the target of discrimination and criminalization?

A notorious neighbourhood

Starting in the 1980s, Canadian poverty and homelessness rates began to rise dramatically for a number of political and economic reasons.

Today, it’s estimated that there are at least 200,000 Canadians who experience homelessness in any given year. Twenty per cent of them are youth between the ages of 16 and 25, and another one per cent are under 16. And these numbers do not include those living on the street or with friends, and who never enter the shelter system.

The capital is certainly not immune to youth homelessness. In the past, Ottawa has responded to this issue by providing more emergency services, such as shelters and drop-in centres. According to the Report Card on Ending Homelessness in Ottawa, prepared annually by the Alliance to End Homelessness Ottawa, there were 379 single youth using Ottawa’s emergency shelters at any point during 2013.

Although the city was able to reduce the overall number of people using shelters by 7.6 per cent—an achievement that earned the city an “A” on its report card—the number of young people relying on shelters decreased by a mere 0.8 per cent. Moreover, the organization found the average length of stay for youth has been on a slight rise year over year, reflecting the larger issue of “an extreme shortage of affordable housing opportunities in the community.”

Emergency services are therefore critical for homeless individuals, especially youth, but their concentration in downtown areas comes with an “unintended consequence,” according to a research paper entitled “Policing Street Youth in Toronto.”

The authors found that emergency services make street youth more visible to the public and the police. Because they have nowhere else to go, they’re forced to spend a lot of time in public spaces. In turn, their increased visibility has a negative impact on public perception.

This was precisely what was happening in Ottawa in 2005, when City Councillor Georges Bédard successfully passed a moratorium—a temporary prohibition—on new homeless services in the downtown core. Bédard felt the concentration of services was turning the area into a sort of ghetto. Two years later, then-Mayor Larry O’Brien stated that by offering so many emergency services, Ottawa was attracting homeless people “like seagulls at the dump.”

The stance taken by these prominent city officials are rooted in stereotypes associated with homelessness, but they also reveal the pressure felt by politicians to take action when faced with the threat of public disorder.

A look at the 2012 Public Survey conducted by the Ottawa Police Service (OPS) shows that residents in the Rideau-Vanier ward continue to be concerned about crime that’s often perceived as being linked to the prevalence of homelessness, such as public intoxication and drug arrests.

In the survey, 74 per cent of ward residents listed the presence of intoxicated persons as one of their top five concerns, while another 72 per cent expressed concern over the presence of drugs and drug dealers. These results are markedly high compared to the average across all wards of only 24 per cent and 43 per cent respectively. One major difference is the visibility of homeless individuals in the downtown area.

“Rideau-Vanier has a sort of notorious history,” said John Ecker, a PhD student in psychology at the U of O. “The public’s perception is warranted to a degree.”

Even so, Ecker, who’s doing his thesis on community integration for the homeless, said the perceived relationship between crime and homelessness is a myth.

“Oftentimes people think that homeless people are all mentally ill and drug addicts and alcoholics,” he said, “but that’s not the case.”

Criminalizing homelessness

Although not all street people necessarily commit criminal offences, some concern regarding the criminal activity of the homeless is nevertheless warranted. Academic studies have found, for example, that street youth are more likely to be involved in shoplifting food and clothing, and consuming drugs and alcohol in public. A small percentage of them are involved in more serious crimes, such as assaults and drug dealing.

“Being homeless did expose me to some criminal activity, mainly theft and drug sales,” said Ferland. “My friend got murdered on the streets and I’ve seen numerous fights.”

“Given the large number of street youth involved in many different forms of criminal activity, it may not be surprising that they are closely monitored by the police,” state the authors of “Policing Street Youth in Toronto.”

This may be part of the reason why the visibility of homeless people is met with a “law-and-order response,” the authors argue. But the added attention of police nevertheless can lead to the criminalization of homelessness. This is what appears to be happening, at least to some extent, here in Ottawa.

Each weekend in September and October of last year, the OPS, in partnership with other local law enforcement agencies, took part in the Nuisance Enforcement Project in the communities of the ByWard Market, Vanier, Sandy Hill and Centretown, in an effort to “address ongoing community concerns in the downtown core,” according to the 2013 Ottawa Police Report. Over the course of those two months, the agencies handed out a total of 1,607 tickets under different acts, including the Ontario Safe Streets Act (OSSA).

“We are working with the local community and residents to address their concerns regarding nuisance offences,” Insp. Chris Rhéaume of the OPS Central District said in the report. “Our approach to violators is education through enforcement of municipal bylaws, provincial statutes and Criminal Code offences.”

The Nuisance Enforcement Project was one of two law enforcement projects led by the OPS in 2013. The service has also been experimenting with “beat cops” in the ByWard Market. Starting in June of last year, officers were on foot patrols in the market during a three-month pilot project aimed at reducing crime in the summer months. In addition to the 59 officers who usually patrolled the market, 14 officers were assigned to walk along various beats in the area.

“We were getting community complaints about vagrancy,” said Rhéaume in the Ottawa Star last year. “Local businesses were worried about it – not just vacancy [sic], but crime and disorder.”

Policing public spaces that are known hotspots for the homeless isn’t anything new.

The OSSA, which came into effect in January 2000, is a provincial law that addressed the rising concerns over aggressive panhandlers and squeegeeing in the late 1990s. Some experts have said that the Act targets homeless people by making activities they engage in, such as sleeping in parks or panhandling, illegal.

“There is certainly no correlation between serious criminality and homelessness,” said Marie-Eve Sylvestre, a law professor at the U of O. “But obviously, because homeless people are occupying and living and working in public spaces, they are often violating bylaws and other provincial statutes which regulate individuals in public spaces.”

For many common offences, then, the question becomes one of causality.

“It’s seems like it’s a chicken and egg situation,” Sylvestre said. “Is it because homeless people are committing more crimes, or is it because we draft legislation so as to criminalize them? It seems to be the latter that applies more than the former.”

A paper published last month called “Challenging Discriminatory and Punitive Responses to Homelessness in Canada,” by Sylvestre and fellow U of O law professor Céline Bellot, discusses the ticketing of homeless individuals in cities across the country.

Although the data presented for certain cities dates back to the early 2000s, the authors’ findings reveal the growing tendency to ticket homeless people under legislation like the OSSA.

In Ottawa, the number of certificates of offences went up to 1,527 in 2006 from 103 in 2000, nearly 15 times more registered offences in the six years after the OSSA was enacted.

Sylvestre said policing homelessness is “not going to address the problem.” Rather, she believes it contributes to fuelling the fear around homeless people.

“People think that if the police are there, then it means … that there is a security issue,” she said, “whereas if you were to replace police officers by street workers or social workers, people would see the problem differently.”

Ecker, who did his comprehensive exam on LGBTQ youth homelessness, called the relationship between police and homeless people “tumultuous.”

“I always find it interesting when a homeless person … gets ticketed for panhandling or something like that,” he said. “First of all, where are they going to get the money to pay for the fine? That just accumulates and can lead to other charges. It’s not a good response to what is clearly a social issue.”

The accumulation of unpaid fines is indeed a problem for homeless individuals. Sylvestre and Bellot’s report states that in Ontario, only 0.3 per cent of all certificates of offences issued against homeless people between 2000 and 2006 were paid. In Ottawa, that amounted to only 14 of the 4,880 registered offences.

The authors concluded that most homeless people are rarely able to pay their fines, and as a result they frequently end up incarcerated.

“Everyone I knew would get ticketed from things such as sleeping in a park … hopping a bus, panhandling, or drinking in public,” Ferland said. “Most people I knew would get ticketed a lot, and since they could not afford to pay, they would let the tickets accumulate to a point where they got stopped for jaywalking and spent a week in jail to pay off tickets.”

The criminalization of homelessness impacts street youth in a unique way, since youth are different than adults in terms of their physical, mental, social, and emotional development. Most of them, especially those under 18, have never had to fend for themselves.

“Youth is tricky, because there’s a lot going on,” said Ecker. “They might be in care systems already, like foster care, they may age out of the system … they may be legally involved or have terrible families sometimes … There are a lot of issues to contend with.”

All this makes the criminalization of homelessness particularly harmful to youth. Being on the street for longer periods of time exposes them to criminal activity and leaves them vulnerable to becoming victims, not just perpetrators, of crime. As a result, they develop a negative view of police and the justice system. Ferland, who is well on her way to becoming a criminal lawyer, continues to believe the system is “flawed” and needs to be fixed.

“The issue (of homelessness) needs to be addressed,” said Sylvestre. “But it’s a matter of deciding who should be dealing with it.”

If the issue isn’t addressed, the marginalization of homeless youth may persist. And stories like Ferland’s will remain an inspiring exception to the rule, rather than a source of change.