U of O students and profs give a rundown of the state of our current electoral system, and the alternative forms of voting that could potentially change it for the better

House of Commons of Canada. Photo: A. Yee

For as long as most university students can remember, political participation (or lack thereof) has been a big problem in Canadian politics.

In the 2008 federal election, voter turnout hit a record low of 58.8 per cent, and in 2011 it rose a meagre 2.3 points. Such low numbers have been the norm for the past two decades in Canada, and with youth voter turnout tabbed at 38.8 per cent in 2011, it doesn’t look like the trend will change anytime soon.

Based on these numbers it seems like something is rotten in the state of our democracy, and some have pointed to our current electoral system as being the culprit.

Throughout this current election, a number of politicians have jumped on board the electoral reform bandwagon, with a number of mainstream political parties promising this kind of change in their electoral platforms.

But what is it about our current system that has three opposition parties calling foul?

Winner-take-all democracy

Right now Canada uses the single member plurality system, also known as first-past-the post, to decide who’s in charge.

In each of our 308 geographic ridings, one Member of Parliament (MP) is elected to the House of Commons. The party that fills the most seats in parliament with their MPs gets to form the new government.

An MP candidate needs the most votes, but not the majority, in order to be elected.

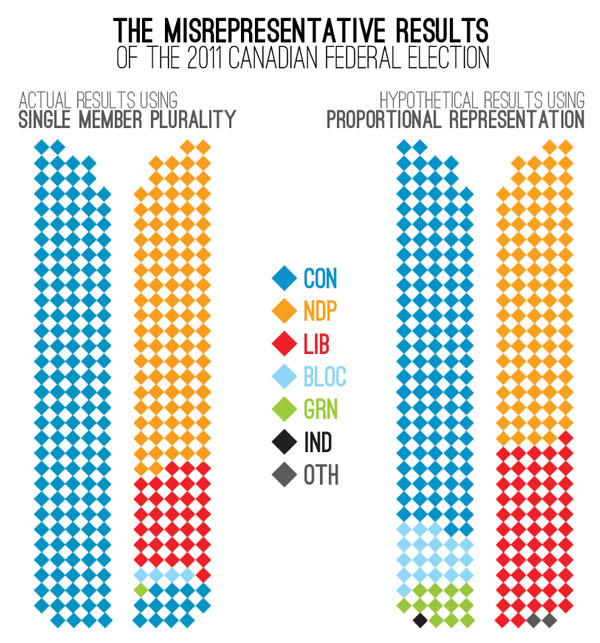

For example, in the last election, Stephen Harper’s Conservative Party won 39.6 per cent of the popular vote. Under the first-past-the-post system, this translated into 166 seats and allowed for a Conservative majority government.

Tony Bui—elections coordinator of the University of Ottawa New Democratic Party—cites these results as an example of how “a party that manages to get less than 50 per cent of the vote still manages to get more than 50 per cent of the power, and, in essence, 100 per cent of the power.”

Still, supporters of first-past-the-post believe that this is worth the sacrifice, mostly because this system is easy to understand and to administer, which, in turn, leads to more political stability.

While Canada’s political process may be in a more reliable than that of a country like Greece (which is going through their fifth election in six years), it still does nothing to deter voter apathy.

According to Jared Maltais—the policy director for the U of O Young Liberals—the current voting system is the fuel that feeds the fire.

He explains that when people know their vote won’t count, “that breeds undemocratic by-products like strategic voting and political apathy.”

Cherie Wong and Felipe Posada—co-presidents of the U of O Young Greens—are particularly concerned by these “undemocratic by-products”.

Wong says that the numbers in the polls don’t accurately reflect actual support for the Green party, since “people don’t actually vote for what they want anymore. They vote for what they think will win.”

Posada adds that in addition to those who vote strategically, there are other would-be Green supporters who choose not to vote at all, and that “it’s (the Green Party’s) main voters that are discouraged by this system.”

Sabrina Sotiriu, a Conservative supporter and PhD candidate in comparative politics at the U of O, says that the Conservative party has no official stance when it comes to electoral reform.

Instead, Sotiriu warns of what she calls the “Harper Derangement Syndrome”. She says that many people are so caught up in ousting Harper and bringing in change that they don’t stop to think about what that change might look like.

So what would change look like? If the Liberals, the New Democrats, and the Greens all want reform, what are they really proposing?

Balancing the scales

Throughout the campaign, in an effort to explain how our democratic process can change, politicians have been tossing around the words ‘proportional representation’ (PR). PR isn’t actually a specific electoral system, but a general characterization of a system.

PR systems award seats based on the percentage of votes each party receives, rather than through a first-past-the-post approach.

In a pure PR system, multiple seats are up for grabs in each riding, and the seats are divided amongst the different parties based on the number of votes they get.

For example, if the last federal election was run under PR rules, the Green Party would have clinched 12 seats in the House of Commons based on their 3.9 per cent of the popular vote (rather than the single seat they received in 2011 by rule of first-past-the-post).

Determining 2011 House of Commons seats using PR voting and first-past-the-post. Illustration: Reine Tejares

A clear benefit of proportional representation, says Posada, is that it would encourage those who don’t think their vote counts, to get out and cast their ballot.

He says that “in a system where every vote counts, every voice is heard.”

Professor Luc Turgeon, a political science expert from the U of O Faculty of Social Sciences, confirms that research indicates a higher level of political participation among countries that use a PR system.

In Canada, when people talk about proportional representation, they are usually referring to something known as mixed member proportional representation (MMP), which is a hybrid between pure PR and first-past-the-post.

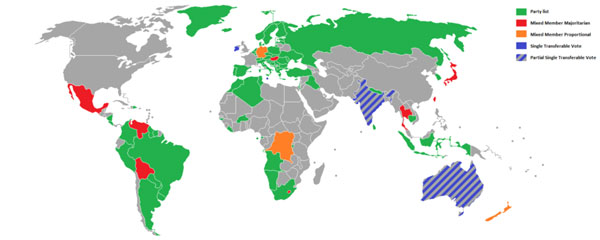

The MMP system is currently employed by countries like Germany and New Zealand, the latter of which abandoned first-past-the-post in 1992.

Where PR voting is used in the world. Illustration: EvilFred

So how does MMP work?

Each ballot is divided into two sections, and each voter gets two votes. In the first section, they select which local candidate they wish to represent their riding in parliament—just as we do now. In the second section they select a national party from the list to support.

The percentage of votes for each party will translate into the percentage of seats they hold in parliament. These seats will first be awarded to candidates who won in their constituencies, and then any remaining seats will be assigned to other party members according to a closed list drafted by the party.

Bui describes the MMP system as the best of both worlds, where “we still have regional representation where the issues of certain areas are still brought forward in the House of Commons, but we also still ensure that every single vote, regardless of where it’s cast, still counts towards the electoral process.”

Turgeon explains that the closed list component of the MMP system would enable party executives to “engineer to make sure that certain groups are represented” within their caucus.

In contrast, the current system puts pressure on local riding associations to select the safest candidates for their campaigns. Turgeon says this is what can lead to things like 80 per cent male party rosters.

However, according to Sotiriu, the problem is that the voter has no say in who appears on this list and in what order.

She warns that closed lists can lead to dirty internal politics to get to the top, and can make MPs less accountable to their own constituents. Turgeon confirms this suspicion and says there is no guarantee that party leaders will put their power of selection to good use.

Preferential voting

With that being said, PR voting isn’t the only alternative electoral system making the rounds in the political circuit.

While no party has officially endorsed the preferential ballot system (also know as instant-runoff voting or alternative vote), the Liberals have thrown its name around a few times in the past.

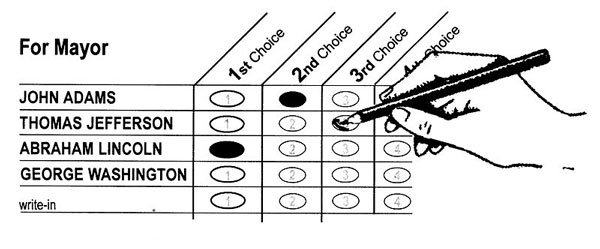

In this system, which has been used in British Columbia, Alberta, and Manitoba in the past for provincial elections, voters rank the candidates in their riding in order of preference. Unlike in our current system, the successful candidate must have more than 50 per cent of the votes in their riding to win.

Ballot for instant run-off voting system. Illustration: Terrill Bouricius

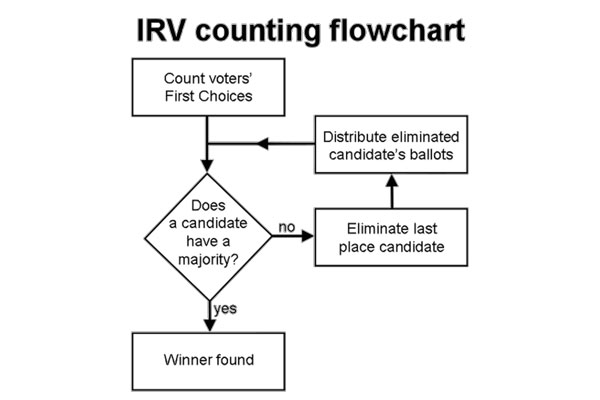

The ranking comes into play if no candidate has a majority of the votes based on the first preferences marked on the ballots. In such a case, the candidate with the least amount of first preference votes is eliminated, and the second-preference votes of those ballots are redistributed among the remaining candidates. This process continues until one candidate has over 50 per cent of the votes.

How the ranking comes into play with a instant-runoff/ preferencial voting system. Illustration: Zerodamage

This type of system would most likely favour the Liberal party, because it largely benefits their position as the centre party. Both Conservative and NDP voters are more likely to put a Liberal candidate as their number two choice.

Unlike MMP, there is no proportional element to this system. If you didn’t vote for the winning candidate in your riding, you don’t have an opportunity to influence the composition of parliament with your vote.

Despite this, Turgeon estimates that a preferential voting system “may be an easier system to sell” than PR. He explains that many people find the MMP system difficult to understand, especially since there are two votes, and that this may lead to a preference for the simpler ranked ballot system.

In comparison with first-past-the-post, the preferential ballot is more much more precise in the selection of MPs. It also gives a much more significant voice to supporters of fringe parties, since the second preferences of ballots for the least supported party are the first to be redistributed.

On the other hand, Daniel Stockemer, a University of Ottawa professor who specializes in electoral systems, warns that “the alternative vote is very strategic.”

Rather than actually voting in order of preference, voters might give their second and third preference votes to parties that they believe have no chance of winning, so as not to endorse parties that are actually competitive with their first choice.

Stockemer also concludes that “the alternative vote will be the worst for the Conservatives. They could get the highest number of votes as first preferences, but they would not get elected.”

Since the Conservatives are the only distinctly right wing party in the running, it’s unlikely that they would get many second preference votes from the supporters of other parties. This means that unless they won a clear majority among the first preferences, they probably wouldn’t win at all.

Sticky status quo

Both of these proposed alternatives have their merits, but will they ever see the light of day in Canada?

In this country, proportional representation has been championed by the NDP, who put forth a motion in 2014 to replace our current system with MMP.

Green Party leader Elizabeth May backed the motion, but according to the Young Greens, this doesn’t indicate a commitment to an MMP system on behalf of the Green Party, but rather a desperate attempt to rescue a democracy which Posada says “is drowning.”

Justin Trudeau, on the other hand, voted against the NDP motion, even though he supports the preferential ballot and is also campaigning on a promise of electoral reform.

Stockemer and Turgeon both express doubts that any of the parties will actually follow through with their promises if elected.

“Parties often talk about changing the electoral system, and then they win,” said Turgeon.

Stockemer explains that “institutions are sticky” and that when people are used to something, it’s unlikely to change.

These forecasts may not be particularly inspirational, but Stockemer maintains that it’s not all doom and gloom. After all, he says, “the (current) system has worked for 150 years and it has always provided some kind of stable, predictable government. So you might say: why change a winning system?”

Sotiriu, who grew up with a proportional representation system in Romania, adds that PR might not live up to Canadians’ high expectations.

She highlights the value of having an accountable local MP. Even if that MP does not represent the political views of all persons in their ridings, they are accountable to and will be at the service of their constituents.

At the end of the day, a lot of these proposed electoral reform hinge on the results of the the upcoming election, especially since the Liberals and NDP have a very real chance of coming out on top. Perhaps change won’t happen in any case, and the cyclical nature of the political machine will squash any chance of voting reform, even if one of the more “progressive” parties is elected to power.

But, then again, you won’t know unless you go out and vote.

Official stance of Canada’s major parties on electoral reform according to Fair Vote Canada

Conservative Party—Has no intention of implementing any kind of electoral reform.

Liberal Party—Is keen on replacing first-past-the-post, but are not sure with what system will take its place. If elected, they are committed to conducting research to determine what is an appropriate substitute.

NDP—Is committed to replacing our first-past-the-post with an MMP system.

Green Party—Believes that electoral reform should be considered a matter of urgency in the next Parliament. Is a firm supporter of proportional representation.

Bloq Québécois—Believes in the need for proportional representation in government, although mostly as a means of working towards Quebec sovereignty.