There are many forces that keep us from loving ourselves—if we let them

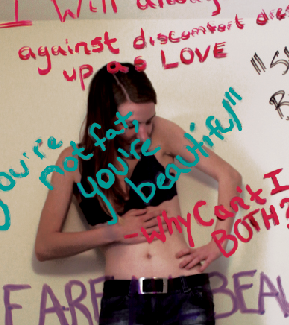

Photos by KayCie Gravelle

Many of us have daily rituals of self-examination that include fat-poking, long periods of mirror-peering, and occasional thoughts of disdain towards our bodies. Sometimes it’s impossible to escape the feeling that we don’t look good in our clothes or that our peers are staring at some part of us that’s abnormal or just plain ugly.

Sadly, these thoughts can consume us and eventually lead us to believe we aren’t good enough to do certain activities or achieve goals we’ve set for ourselves. Though most of us have an unhealthy body image, many of us don’t realize the reasons for body shame and what it can do to us overtime.

Let’s get physical

Body shame involves inappropriate, negative, or derogatory comments and attitudes about one’s own or another’s body. It’s the desire to hide or change some bodily betrayal that doesn’t meet internal or external approval and tends to centre on the idea that a person’s worth should be measured solely on aspects of their appearance.

“There is no essence to being pretty with relation to a person’s character,” says Lia Walsh, a University of Ottawa Spanish graduate student. “It’s just a physical description.”

Walsh has memories of her own experiences with body shame. She remembers feelings of inadequacy when she realized her girlfriend didn’t like her body.

“There were moments when I forgot that I was anything more,” she says, “especially because I got the distinct impression that my body wasn’t an object of desire. She would say I was sexy, but I knew she wasn’t talking about my body. When I told her I’d been accidentally losing weight, she responded, ‘Oh my God, just think, I’ll get you, and in a sexy body.”‘

Walsh’s girlfriend made her feel as though she wasn’t a whole person; her body and mind were separate. In the eyes of a body-shamer, the body holds importance over the mind. This applies to the way we shame ourselves. We generally neglect the great facets of our personality and break ourselves down to a body that only deserves a verbal beating.

Matters of the mind

Though body shaming is about reducing a person to the shape and size of their body, the problems lie completely in the mind because it has to do with the way we perceive our own bodies and the bodies of others.

Since there is a strong connection between emotions and actions, body shame often leads to harmful behaviours towards the body and other mental health issues like eating disorders, unhealthy sexual practices, anxiety, and depression. More often than not, feelings of uncertainty, incompetence, and self-consciousness are persuasive enough to make people skip the gym, pool, or birthday cake.

Body shame has no boundaries; it’s universal and spans across all ethnicities, ages, and genders. In particular, the implications for students are immense. Shame is a collection of disorderly thoughts that often consume mental space in a student’s mind. Why? University aims to create independent thinkers, but in truth, the university culture is one that is extremely socially dependent. How a student fits in with the preconceptions of friends, family, peers, and university life often has more sway in student success than actual academic achievement.

According to Amanda Robertson, a counsellor at the Student Academic Success Service (SASS), body shame is generally a feeling we internalize.

“Shame is a quiet secret,” she says. “‘I’m never enough,’ be it thinner, heavier, curvier, sexier, prettier, healthier, or smarter.”

She says these feelings of not being good enough create a powerful mental barrier that barricades our potential for personal growth and self-confidence at school and in the workplace.

The ideal isn’t real

Lindsey MacIssac, a counsellor at Ottawa’s Hopewell Centre for Eating Disorders, lays the blame of unhealthy body image on extrinsic opinions.

“Shame revolves around hiding the inner conflict and turmoil about the part of ourselves that doesn’t match up with what society suggests,” she says.

Society, in this instance, refers to strangers, peers, family, and the worst culprit: the media. In studies performed by the National Eating DisordersAssociation, an increase of media use is related to an increase in body dissatisfaction.

For example, research from Amy Farrell, a professor of women’s and gender studies at Dickinson College, states that before there was television in Fiji, much of the population was overweight since a robust appearance was associated with strength and the ability to do hard labour. There wasn’t social dissatisfaction toward body fat until the arrival of television and Western programming, which caused the Fijian population to pursue the thin ideal.

Television shows like Friends, How I Met Your Mother, and New Girl, which are supposed to depict everyday scenarios, usually don’t depict everyday people or bodies. Women are thin and have overdone makeup, hair, and flawless skin, while men generally have toned bodies and qualities that showcase them as stereotypically masculine, like beards or chin stubble and chiselled jaw lines.

In all three of the shows listed above, certain characters don fat suits to show either weight gain in the show or flashbacks to when they were rounder, and all are mocked by other characters in the show. Therefore, the viewer is left with the impression that bodies other than those depicted normally on the show are unusual and are sources of ridicule. In reality, these “abnormal” bodies are the norm.

Statistics Canada states that in 2012, almost 60 per cent of men and 45 per cent of women were overweight or obese.

Similarly, body-shaming comments are also made in regards to thin people in the media. Men are considered nerdy or scrawny if they are too thin, and oftentimes the press hounds women in Hollywood who lose too much weight.

Are our bodies really our own?

Naomi Martey, a volunteer at the Women’s Resource Centre at the U of O, says people have lost possession of their own bodies.

“Bodies are treated as a public space that we are simply moving through, in which others feel that they have the right to pass judgement,” she says.

Because the media showcases bodies as objects by treating them as jokes, they have become the property of the onlooker.

Walsh uses the example of going to the gym to lose weight. If she went to the gym, she says she’d face looks of judgment from other gym users. If she didn’t go to the gym, she would remember the preconception of being “useless, lazy, and disgusting,” associated with skipping the exercise.

The way Walsh felt about herself and her choices was based completely on the fear of the judgments of others around her. She wasn’t the owner of her body or in control of how she felt about it.

Though we may recognize that we are our harshest critics, others make constant judgments that prevent us from escaping the feelings that we aren’t worthy or that our bodies are ugly.

Even family members can feel the need to take control of our bodies. Though our parents or other relatives believe they are helping to keep us healthy, little comments about diet, exercise, or appearances usually do more harm than good.

The comments Walsh’s family made about her body, eating habits, and lifestyle choices often made her feel restricted and defeated.

“The things they would say about my body didn’t make me want to eat less, go for a jog, or tell them the truth,” she says. “It made me want to curl up on [the] couch, in sweats, and eat a tub of ice cream.”

Beating body shame

Martey explains that talking about the issues in society regarding body shame and about how we feel about our own bodies is necessary to teach each other how to be accepting of all bodies.

“When we see people like ourselves and hear their story, we can use that to heal and, in turn, share our own stories,” she says.

TEDx Talk expert and shame researcher Brené Brown reiterates that the most important tool we have to eliminate shame is our voices.

“We have to talk about shame,” she says. “Empathy is the antidote to shame.”

The only way to empathize with someone is to discuss their issue and fully understand how they feel. Starting these conversations is fundamental to beating body shame.

The U of O offers a number of resources including Health Services, SASS Counselling and Coaching, the Pride Centre, the Women’s Resource Centre, and the Peer Help Centre. These are go-to places to discuss possible insecurities and fears about body appearance.

Body Image Positive is a blog and community started by Walsh to educate on body shame and other issues effecting self-esteem. The blog offers interesting articles on body shame and is a resource to discuss opinions on the problem.

The only restrictions and limitations of the mind are those imposed by society, but by casting those aside through discussion and understanding, we can work toward eliminating body shame for good.