What does it mean to be an ally? Sabrina Nemis writes about supporting marginalized communities without taking over the conversation.

Photo illustration by Tina Wallace

To be an ally

It was a text read around the world, but mostly because he wanted you to.

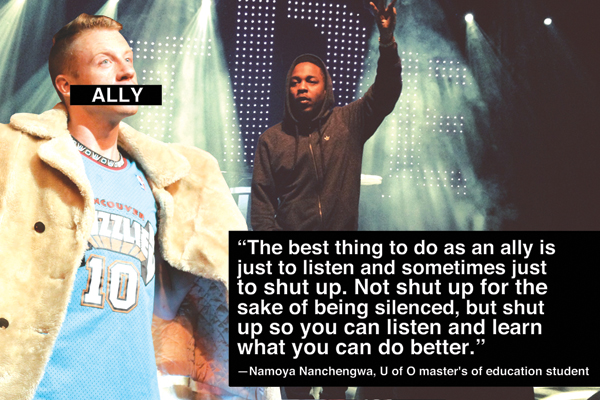

After the Grammys on Sunday, Jan. 26, Macklemore posted a photo of a text he sent to fellow nominee Kendrick Lamar.

It read, “You got robbed. I wanted you to win. You should have. It’s weird and it sucks that I robbed you. I was gonna say that during the speech. Then the music started playing during my speech and I froze. Anyway you know what it is. Congrats on this year and your music.”

As the only white person nominated for Best Rap Album, a category of music created by and traditionally dominated by black voices, Macklemore’s Grammy win could be deemed problematic from the beginning.

The win on its own could have been discussed and debated on the merits of its significance in modern pop culture. However, the text derailed this conversation as it brought questions of allyship to the forefront — an ally being someone who fights the oppression of marginalized people, regardless of whether that person identifies within that group of people.

The text was discussed on Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, personal blogs, music and news websites, as well as in casual conversation. Commenters were divided in their interpretations of the text as either an act of solidarity or Macklemore’s attempt to create more buzz about himself than the black artists unrecognized by the award show.

“In a way, it was a microcosm of what irks people about Macklemore in the first place: He can’t do something good without using it to call attention back to himself,” wrote Marc Hogan of Spin magazine.

While some might dismiss the discussion as nothing more than inflated celebrity gossip, Elaine Lui, a long-time celebrity blogger and reporter for CTV’s eTalk, says in her TEDx talk that examining celebrities is a way “to understand social culture, to understand social behaviour, to understand humanity, to understand ourselves.”

Allies online

According to Namoya Nanchengwa, a master’s of education student at the University of Ottawa who is active in social media and participates in discussions of allyship online, social media has become an effective way of educating and engaging people in new ideas.

“I think a lot of oppressed communities are finding their voices online,” she said. “There have always been activist movements, but they’ve sort of been localized and haven’t really had a stage. What I think the media does is give them a bigger stage to talk about these issues.”

With the rise of discussion in marginalized communities comes a rise in awareness for everyone else about these issues. Many people are eager to be supportive and to get involved in movements that aren’t their own. But this is something Quinn Blue, coordinator of the Pride Centre at the U of O, deems potentially problematic.

“I think one thing that I see sometimes is people trying to be really enthusiastic when they get involved, which is amazing, but not necessarily taking the time to educate themselves about issues or taking the time to listen to what people within those communities are saying, and are just making assumptions about how to do this work,” he said. “I think that can be really hard sometimes because people are so well-meaning and I really want to encourage that enthusiasm.”

At its most basic level, being an ally requires an understanding of the issues affecting a marginalized community or movement. Whether one intends to aid women as feminists, stand in solidarity with people of colour, or support those with disabilities, it’s important to understand the historical and social context of the challenges facing a group of people.

“The first thing that should be done, if you want to be an ally, is to educate yourself,” said Nanchengwa.

Because of the Internet, educating oneself can be as easy as visiting a website dedicated to discussing various movements and the issues that face them. Websites like Feministing or Racialicious provide articles about pop culture trends from a feminist or racially conscious lens and a community of people with whom to discuss these ideas.

Within these discussions, members of marginalized communities also have the opportunity to debate what the most important issues are and how allies can best support them.

The Macklemore debate

Author and sex advice columnist Dan Savage posted a video on his blog The Stranger of LGBTQ+ YouTube sensation Arielle Scarcella praising Macklemore for taking steps to be an ally to the LGBTQ+ community with his song, “Same Love.” He performed the song at the Grammys as Queen Latifah presided over the marriage of 33 couples.

Savage and Scarcella asked members of the LGBTQ+ community not to criticize Macklemore in his allyship, as they’re concerned this will alienate allies and discourage them from showing their support.

In an article for Flavorwire, Tylor Coates disagrees and offers an alternative to praising Macklemore for his debated allyship.

“A better take on this?” he wrote. “The acknowledgment that figures like Macklemore are complicated, because they do, at times, recognize the privilege they hold, yet still use it for their own gain while promoting tolerance and equality.”

Both through a song about marriage equality and through his text acknowledging his privilege in winning best rap album, Macklemore is functioning as an ally by using his privilege to bring conversations about marginalized people into the public discourse. Where his actions have been interpreted as a failure is in the perception that he’s used these issues to talk more about himself than about the people he claims to support.

“I just don’t dig that the song chosen this year to celebrate the national movement toward equality begins with a description of what it feels like to be straight but fear you might be gay,” LGBTQ+ comedian Cameron Esposito wrote on her Tumblr. “The song puts thinking you are gay in as part of a list of things to be sad about — to cry about even — and as a gay person, this upsets me. It’s tough to be defended by someone who would be bummed to be you.”

Macklemore’s text to Kendrick Lamar is being deemed problematic because he shared an Instagram photo of it. While publicly acknowledging the failure of the Grammys to support black artists is not a bad thing, to some, the text seemed more like a bid for approval that refocused the attention on Macklemore as an ally, rather than on how mainstream media often overlooks marginalized artists.

Blue said the idea of using one’s privileged position in society to speak out as an ally can be complicated but it can be positive when people use privileged spaces to spread the messages of those in less privileged positions.

Becoming an ally

According to Nicole Desnoyers, vp equity of the Student Federation of the University of Ottawa (SFUO), students looking to get involved in movements at the U of O should identify the student leaders of relevant clubs and associations on campus, find out how to get involved, and then listen to what members have to say.

“Being an ally can be really scary because it means that you have to listen,” she said. “Don’t be shy, don’t be afraid to be in that secondary, background role, and be enthusiastic about it.”

According to Nanchengwa, though participating in discussions can be a method of staying engaged, it’s important not to drown out the voices of members of a marginalized community.

“The best thing to do as an ally is just to listen and sometimes just to shut up,” said Nanchengwa. “Not shut up for the sake of being silenced, but shut up so you can listen and learn what you can do better.”

Blue recommended ally training with the Pride Centre as an opportunity to learn more about issues facing LGBTQ+ communities.

With Macklemore, although his text may seem self-congratulatory, as a white, cisgendered, straight male who performed at the Grammys and won four awards, his voice carries more weight with the media than LGBTQ+ and black performers who were nominees or not nominated at all.

For non-celebrities, speaking up in privileged spaces can mean speaking out against racism if you’re racialized white, trans and homophobia if you’re cisgendered and straight, or ableism if you’re able-bodied.

“What I think allies could do if a person like me asks them to jump into the conversation, is they could help prop you up,” says Nanchengwa. “They could also do things within their community, within their circle of people, to educate the people around them to start to think about these issues.”

She adds, “Being an ally is just being a good, decent human being. You should be doing this anyway.”

As more individuals continue to learn about marginalized communities through the allyship of celebrities, online research, and involvement in groups working for social justice, the institutions supporting oppression should also be challenged.

Whether it’s the Grammys including the rap awards in their network television broadcasts or the inclusion of different Canadian experiences in government-mandated school curricula, institutions impacting the behaviour and thoughts of many people still uphold a narrow view of what normal is.

Educated individuals who have been listening and paying attention are primed to make institutional changes when the opportunities present themselves. Becoming an effective ally in day-to-day life means a commitment to ending oppression when one encounters it and being open to constantly re-evaluating the best way to be an ally.

We all make mistakes

Sometimes even the most liberal, accepting, and educated allies can make mistakes. According to Desnoyers, erring is part of the learning process when it comes to being an ally.

“No one is the perfect ally,” she said. “There’s no such thing. There’s no allyship badge or button that you can get.”

Desnoyers’ position with the SFUO was newly created for this school year and demonstrates a movement at the U of O to acknowledge students who are part of marginalized communities on campus. Her portfolio has largely focused on fighting for indigenous rights and against homophobia, as these are the communities with which she personally identifies.

“The vp equity portfolio needs to be addressing discrimination for all students, like racism for example,” she said. “I should be focusing on that as part of my portfolio, but I am not a racialized student who experiences racism every day. So is it my place to lead the charge?

“One thing I’ve been working on, especially with Ikram (Hamoud), vp services and communications, is creating campaigns that give empowerment to students without me being the leader.”

As she works to facilitate conversations for students across campus this year, she hopes the next vp equity will be able to build on the work she’s done.

“I would like the next vp equity to be able to pull from their own experiences and from their own identities to make work around that happen,” she said. “I think it’s going to be very interesting to see this portfolio over the years as different types of vp equity come in.

“At the end of the day, I know I’ve made mistakes, whether that’s been pointed out to me or not,” she added. “I know that I need to continue learning and unlearning what I’ve already internalized to continue evolving as an ally.”