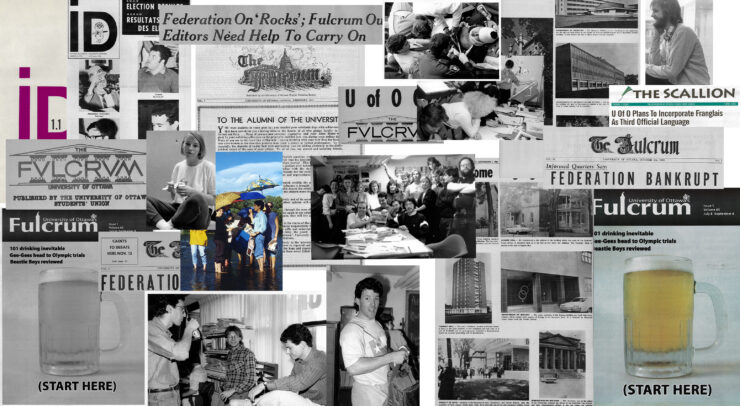

Former editors-in-chief reflect on time spent producing the newspaper

With the Student Choice Initiative looming and the cost of print a burden on the outlet’s budget, the Fulcrum printed its last physical issue at the end of the 2018-19 publishing year. It was a struggle to the finish line as the Fulcrum had to rely on crowdfunding to cover the printing costs of its last physical issue.

“Finally, a special thank you goes out to the following people and publications for their overwhelming support for our GoFundMe campaign to help us fund our last print issue ever, a reality which didn’t seem possible at the time due to a delay in receiving our student levies this year,” wrote the Fulcrum’s 2018-19 editorial board in its final print editorial.

Since then, the outlet has revived its classic ‘front to back issues’ — albeit in a different fashion as the outlet now publishes digitally. These ‘issues’ have enlightened the current editorial board to the frustrations and joys that arise in the process of producing a (digital) newspaper.

Although there may be a fair share of frustrating moments, these do not equivocate with the annoyances of former editorial boards who for the most part of the Fulcrum’s history did not possess the luxury of a digital layout program or the internet.

However, ‘print night’ still resulted in fond memories, christened friendships and copious amounts of alcohol. With that in mind, the Fulcrum decided to look back at its history this week and glance at how the process of producing changed over the decades. To get somewhat of an idea, the Fulcrum interviewed 11 former editors-in-chief who shared some of their best stories and memories along the way.

Wax, scissors and taxi drivers

For most of its 81-volume history, the Fulcrum had to physically create its templates and layouts using hot wax, rollers, scissors and darkrooms.

“Production was literally a matter of cutting out the columns,” said Steve Coughlan, the Fulcrum’s editor-in-chief (EIC) for the 1978-79 publishing year.

“You would roll [hot wax] on the back of the copy that either we had printed ourselves … and then physically put it on to the templates of the pages that we had to put together.”

The analog process was a very hands-on affair; production managers had to be very accurate with their work, there was no undo function.

However, according to Coughlan, having a “type-machine” helped the Fulcrum a lot with last-minute changes when deciding on headlines, font size and picture size

“Having the typesetting machine obviously made that a lot better. You could have your headline in like 36 points and you thought, ‘You know, it should be a little bit bigger to actually fill the space.’ So we’ll go and reprint it in 40 points and so on.”

As much as it may sound archaic by today’s standards, there are a lot of similarities including the ‘challenge’ of creating cohesive and comprehensive page layouts for readers.

“We’d get the old fashioned cutters, and we cut [articles] out to insert them into the columns … there was a certain amount of artistic freedom involved in how you would place your columns,” said Sonia Desmarais, EIC for the 1990-91 publishing year.

If not attentive, the process could result in numerous mistakes, which can often be the case when interacting with co-workers and attempting to create a newspaper.

“I remember when I was sports editor, I wrote an article on this engineer on the football team that was five foot five, he was so happy to have this profile written on him,” said Desmarais. “As I was cutting and pasting, I accidentally inverted two paragraphs so when [it] came out there was like this whole section that was illegible.”

“I remember it to this day [and] I’m horrified. I think back and I can’t believe I put out a newspaper with two sections completely inverted.”

With no information superhighway, the newspaper could not simply be emailed to the printer as in later years. With the Fulcrum’s printing partner out in Smith Falls, the outlet had to depend on taxi drivers to deliver its crown jewel to the printer.

“The taxi would pick it up, so my last job [as EIC] was to put everything in a box and get it ready for the taxi driver who would drive it to the printer,” said Mark McCarvill, EIC for the 1987-88 publishing year.

Sending the final copy of the paper off by itself every week with no back up, however, didn’t worry the team at the time.

“So I had never heard any horror stories about ‘Oh, this taxi driver lost it or whatever,’ ” he said. “That’s how it was back then … nowadays, I’d never do it that way.”

When it came to adding visuals to the paper, the Fulcrum was reliant on film cameras and darkrooms.

In Coughlan’s year as EIC, Fulcrum photographer Hugh Mackenzie inadvertently went out to take what he thought was a standard group photo but instead, ended up photographing an engineering frosh prank. The image captured the moment so well it made its way into Life Magazine after being picked up by the Ottawa Citizen and Canadian Press.

Moving into its current office at 631 King Edward Ave. in the late 1980s, the Fulcrum kept printing photos themselves until the early 2000s.

Jonathan Greenan who worked for the Fulcrum for four publishing years from 1998-99 to 2001-02 lived through several changes that brought the paper into the digital age.

“We were, I guess, not quite into the digital age yet, in the late 90s, in terms of how a lot of the paper was put together. We were still very much analog,” said Greenan, who served as EIC from 2000 to 2002, and was also a Jeopardy! champion.

“We still had a darkroom that was fully functional within the office. We still typically would wax the pages that we actually laid out the stories and photos on and then apply the ads and photos and cutout stories to the wax paper.”

When he took over in 2000, the process had changed.

“By the time I was EIC, the waxer had gone the way of the dodo.”

Watching the sunrise at the office

One constant throughout Fulcrum history has been the ritual of staff staying up until the wee hours of the morning to complete the paper. Every single person the Fulcrum interviewed mentioned how late they would stay confined to the grounds of the Deja-Vu spaces or Fulcrum offices.

“Officially by Tuesday at 11 p.m. everything was supposed to be done, but it was almost never done,” said Sabrina Nemis, EIC for the 2014-15 publishing year. “I was often there till three or four in the morning.”

Before our interview with Mario Emond even began, the 1987-88 EIC asked us how things had evolved in terms of our late nights as compared to his. He then proceeded to give a very detailed recount of his sleepless nights at the office.

“Chaos, a very well managed chaos, we got things done but there was no [real] orderly process for it. It just happened … these were late nights [that] would sometimes go till six in the morning,” said Emond.

“We were all very exhausted afterward. … [but] we couldn’t go straight home to sleep. We were just so wired [and] you need to decompress after that.”

Depending on the publishing time, upon leaving the office, the staff would usually go celebrate over a cold beer or a piece of toast at a local establishment nearby the office. It wasn’t unusual for the editors to “stagger in bleary-eyed” and enjoy a team breakfast according to McCarvill.

“I remember coming home after having a bite after production somewhere down in the Byward Market. We’d go down for a chocolate milkshake at three or four o’clock in the morning to the one place that was open 24 hours. And that’s because we got the paper to bed,” shared Brett Ballah, the EIC for the 1995-96 publishing year.

“Whether we finished at 2:00 a.m. or at 6:00 a.m., tradition would take us to one of several all-night diners that still existed in the market area, on Dalhousie,” said Dominique Roussel, the EIC in 1984-85.

“There amidst characters from a Tom Waits song, on a very cold winter night, we’d savour our victory and replay the night’s labour.”

Unforgettable memories

Despite the stress and hard labour associated with ‘production nights,’ everyone seemed to hold very fond memories of the events.

“It doesn’t feel like that long ago, some of the memories are very vivid still because of the intensity and the adrenaline that you showed up with. And people were really committed to it, although it was still somewhat of a chaotic process,” reflected Emond.

Adam Feibel, EIC for the 2013-14 year, is still very good friends with his production manager Rebecca Potter, so much so that he insisted they do a joint interview with the Fulcrum.

McCarvill even remembered the music that played on those late nights and the meals that were shared.

“There would be a bunch of people working together, the music would be blasting, we’d have Elvis Costello, blasting, “Pump It Up.” We’d have all kinds of other music to keep our energy up because it’s gruelling going from, I don’t know, three, four in the afternoon to six in the morning.”

“All-nighters, I couldn’t do that today, it’s really gruelling. So we [kept] our energy up. We’d have pizza or something halfway through the night and just go step by step and get giddy and joke around,” he added.

Adam Grachnik, EIC for the 2002-03 publishing year, shared that on ‘production nights’ he had some of the most passionate arguments of his life — in a good way.

“There was so much sweat and emotion that went into it … I remember the comradery and the heated arguments and looking back now I don’t think I’ve had a more passionate argument in my life than over a headline at the Fulcrum,” said Grachnik. “I learned a lot of tremendous lessons at the Fulcrum about working with people and producing something that matters.”

Finally, one story that stood out was the tale of ‘production day’ on Sept. 11, 2001, which was touched on by both Grachnik and Greenan.

“We showed up Tuesday morning, same time we’d normally be rolling in around 8:30 a.m. and I remember Ian [Chapstick, then production manager], and I went for cigarettes on the front porch. And one of the staffers from O.P.I.R.G [the group occupying the third floor of the Fulcrum building at the time] came down to say the World Trade Center had been hit by a plane,” said Greenan.

“We didn’t have a TV in the office and the internet was slow as molasses that day, so we walked to my house to pick up my little 13-inch tube TV and bring it back. By the time we were on our way back, probably around 10:30 a.m., they were now diverting every flight in the North American airspace to whatever airport they could land them at. So we were walking back, and a plane came in super low over a route that a plane never comes in low. And I remember all of us just looked up at this, this plane coming in low, like ‘What’s going on here?’ ”

Greenan then explained that his brother Mark, who was the Ottawa bureau chief for the Canadian University Press (CUP) and a member of the press gallery at Parliament Hill, arrived at the Fulcrum office around noon. The then EIC asked him to go to the parliament and try to get as much info as possible about the day’s events.

“The story that Adam tells all the time, and every time 9/11 rolls around (my Fulcrum friends inevitably end up communicating with each other about 9/11 production day) [is that] Adam remembers me giving Mark a hug and sending him off to Parliament because we didn’t know what was going on,” said Greenan.

“It was a crazy day.”