U of O signs on to Access Copyright until 2015

Jane Lytvynenko | Fulcrum Contributor

Photos by Justin Labelle

On June 30, the University of Ottawa administration agreed to sign on with the Access Copyright model license until 2015, despite opposition from the undergraduate and graduate student federations. Access Copyright, an organization licensing intellectual property on behalf of universities, has increased its tariff with the new agreement, now charging universities $26 per student for its services.

What is Access Copyright?

Established in 1988, Access Copyright is the sole provider of copyright-protected works to Canadian colleges and universities. This includes the right to copy parts of a book or news source, include material in course packs, and convert works into digital formats. Leslie Weir, the U of O chief librarian, said the university has been working with Access Copyright for over 20 years.

“Access Copyright represents [the] creators’ collective, and they are responsible in making sure creators get paid for their work,” Weir said in an interview with the Fulcrum. “And I think all of us want the creators to be paid for their intellectual property.”

According to Weir, the university has three different ways of paying for intellectual property: licenses the library acquires directly, Access Copyright, and a direct transaction—asking the author directly for permission to copy their work.

The new model license

Before the start of the 2012–13 academic year, students paid 10 cents per page of intellectual property, in addition to $14–18 per student yearly. The new model license has students paying $26 each but also includes new, cheaper ways for students to take advantage of intellectual property.

The 10-cent page fee has now been removed, lowering the price of course packs. According to Sebastien Dignard, who oversees the DocUcentre on campus, students will now pay close to $0 for copyright fees per course pack, as opposed to the previous average of $22.50 per course pack in copyright fees.

Maureen Cavan, executive director at Access Copyright, said that although there is a significant price difference between the previous old annual fees and the fees students pay now, the two are not comparable.

“The price increase is nothing you can calculate directly, because the new license involves new uses,” she said. “You can now make digital copies, which was never included before the license.

“You can copy up to 20 per cent of a book, a full chapter, or an article from a magazine, journal, or newspaper, and can also use those in digital form.”

Pricing and alternatives

Weir said the $26 per student price is hefty despite the new privileges. Although Access Copyright was originally hoping to charge $45 per student, the Copyright Board of Canada set the tariff at $26. Allan Rock, University of Ottawa president, said several other universities agreed on the price while others left the company. Cavan said about 65 per cent of universities and colleges across Canada signed on to the model license.

“We also looked at the relative cost of staying and dropping out, and it’s not the same. It’s more expensive to stay in, but not by a lot,” Rock explained.

“There will be a cost that has to be passed on to students, which is regrettable,” he added. “But there was a cost that would have been passed on to students anyway, perhaps slightly less.”

Rock said it would cost about $500,000 to set up an in-house copyright office and another $500,000 yearly to keep it operational. Those prices do not include costs of equipment.

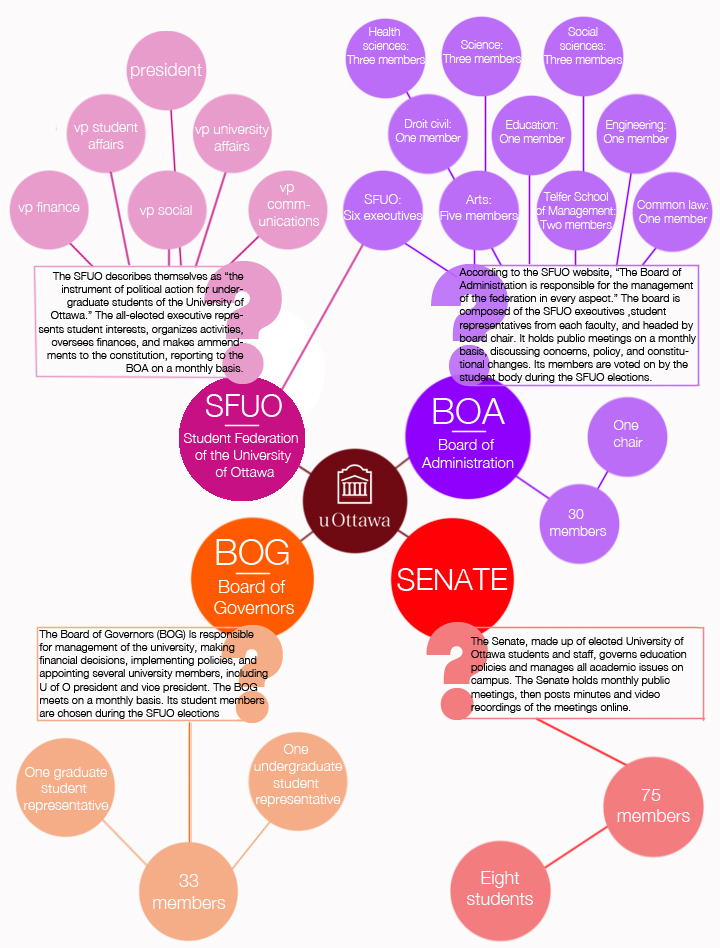

Recently, some universities have started cutting Access Copyright out of the equation to save money, opting to acquire licenses themselves. Elizabeth Kessler, vp university affairs at the Student Federation of the University of Ottawa (SFUO), said we should have been doing that all along. Kessler said the university should be absorbing the new Access Copyright expenses while working on an in-house office.

“We know the university has the money—they have a $41 million surplus—and they certainly have more than enough to pay instead of putting the cost off to students,” she said.

Kessler said the SFUO urged the U of O administration not to sign the model license, believing it to be a bad deal for students; however, according to Rock, with the close deadline of June 30 and no in-house office set up, the university had little choice.

“The reason we didn’t get out right now is [that] if we do get out of Access Copyright, we have to have a system of self-administration to make sure that copyright is respected on the campus,” said Rock.

“Some universities, Carleton included, have spent the time and money over the last few years to put a self-administration system in place. We have not,” he continued.

Cavan says one of the biggest benefits of Access Copyright is that it makes copyright issues for universities simple by taking on all the work and responsibilities.

“It’s easy. [Without Access Copyright] you have to get direct permission from the publisher, and if the university had not negotiated an independent direct subscription license with a publisher and you want to use some work from that publisher, you would have to call that publisher and get permission,” she said. “That’s what a collective license relieves.”

Kessler said a problem with Access Copyright is that although it does provide plenty of materials to students, there is no comprehensive list of what works and publishers it oversees. Weir said the university will launch a study this year to determine which works are being copied by students.

“The library pays for licensing of electronic resources, and we have Access covering things we don’t license,” said Weir. “But we feel we might actually be paying twice, because we may be paying Access Copyright for stuff we are already licensing.”

Meanwhile, students will be paying the majority of Access Copyright costs until Dec. 31, 2015. Rock said that until then, the university will work to establish an in-house copyright office while covering part of the model license costs for the next three years.

“As soon as we can get out of this thing,” said Rock, “we will get out of this thing.”

—With files from Andrew Ikeman