U of O president furious outlet used 2017 data

University of Ottawa president Jacques Frémont lashed out at a recent article published by the Globe and Mail while delivering his officer’s report for the U of O Board of Governors (BOG) on Jan. 25.

Written by investigative journalists Robyn Doolittle and Chen Wang, the article broke down the numbers behind the ‘power gap’ at multiple Canadian universities and showed a less-than-stellar portrait of the U of O.

“They [the Globe and Mail] wrote that we [the U of O] are one of 10 notoriously lagging institutions in terms of gender balance and equity,” said Frémont.

“This is completely irresponsible journalism and the Globe and Mail used to be better than that,” he continued.

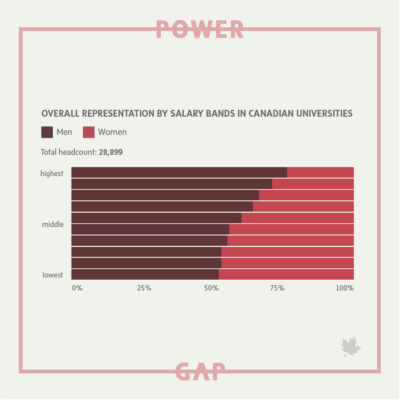

The piece is one of four in a series highlighting the wage disparities between men and women employed in Canada’s public sector.

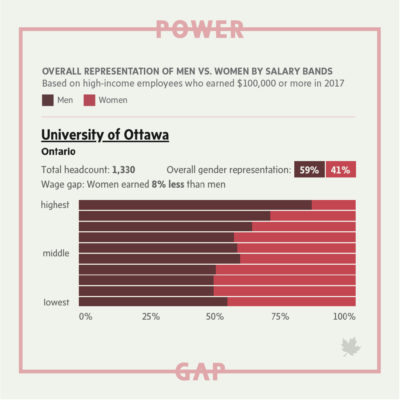

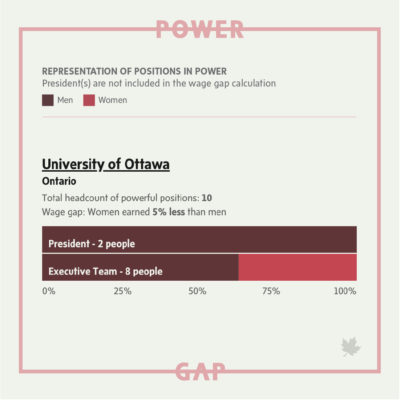

The article included a number of graphics using data relating to the number of men and women in executive positions (president, provost, vice-presidents). The piece also included graphics that broke down all employees with annual salaries above $100,000.

The results for the U of O, which were specifically from 2017, showed a fairly equal gender balance at the university for employees making salaries in the lowest range of around $100,000 with around 50 per cent of employees identifying as women.

When it came to top earners at the university, however, women were underrepresented. This was specifically highlighted in the U of O’s executive team at the time.

In 2017, the university’s executive team was made up of eight people, five of which were men. These included vice-presidents Michel Laurier, Christian Detellier, Marc Joyal, Louis De Melo, David Graham, Diane Davidson and Mona Nemer, as well as vice-provost Claire Turenne-Sjolander.

At the BOG, Frémont stated that the inscribed statistics were “five years out of date which is gross for quality journalism,” and assured his audience that “we [the University of Ottawa] are nowhere near what the Globe and Mail pretends we are.”

When speaking to the Fulcrum, Doolittle confirmed the article “is meant to be a snapshot of what the workforce looked like in 2017. It is not meant to say that this is the exact same as it is today.”

The article itself went on to say that, “The Globe’s data comes from the 2017 or 2017/2018, depending on how the organization handles its fiscal year.”

The goal of the Globe and Mail article was to address how “women overtook men in graduating university classes 30 years ago” and ask the question “why are they still underrepresented everywhere?” she explained.

“We [the Globe and Mail Power Gap team] are devoting this entire year [2021] to investigating why women are not rising at the same rate as men,” stated Doolittle. “Why are they continuing to be outnumbered, outranked, and outearned by almost every measure.”

Doolittle admitted that the numbers presented in the article were subject to change over time but the numbers simply provided a glimpse into the wage gap four years ago.

“It’s entirely possible that you’re going to see a turnover [in executive teams], but looking at the gender divide at the very top in 2017: it was proportionately more men.”

Despite Frémont’s displeasure with the data presented in the article, Doolittle confirmed she contacted every university mentioned in the article in November 2020 with the results of the data and invited each of them to comment.

“There are lots of women making over six figures, and very few women among the top earners at universities. And that is not the Globe and Mail’s opinion. That’s just what the data showed.”

In an email to the Fulcrum, the U of O reiterated comments made following the release of the Globe and Mail article “the data [the Globe and Mail] used is from 2017-2018 and therefore at least three years out of date. Since 2017, the university’s presidents, provosts and some of its vice-presidents have changed.”

Doolittle plans to write an update on wage disparities in the public sector in coming years, and eventually plans to examine private sector companies.

“The reality is it took us two years to collect all of this data, analyze it, clean it, [and] fact check it,” said Doolittle. “In a few years we are going to redo all the data to provide a new snapshot.”

At the end of the BOG meeting, Frémont reiterated his frustration with the information presented.

“What you read in the newspaper and the reality is outrageously different. I can’t believe the Globe and Mail would go forward with this [article].”