New study could help combat the effects of climate change on coffee

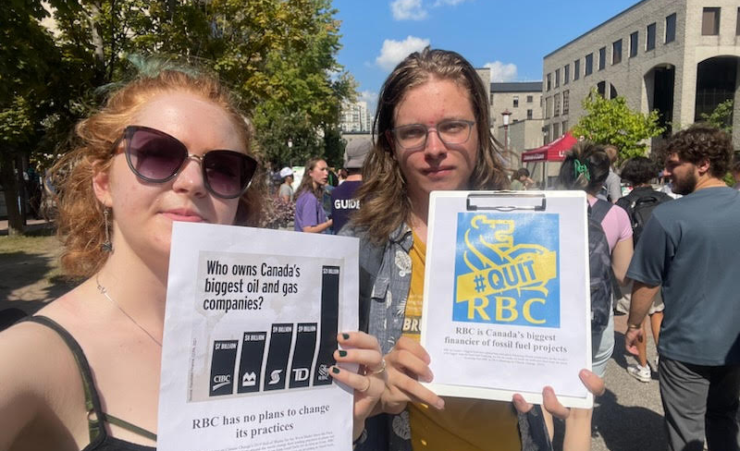

Photo by Brianna Campigotto

Researchers from the University of Ottawa have made an astounding discovery about your morning brew.

The team, led by research chair David Sankoff, have managed to sequence the genome of the Robusta species of coffee.

After water, coffee and tea are the most commonly consumed beverages in the world. Of the dozens of species of coffee plants, Arabica and Robusta coffee are the only species that are grown and cultivated.

“We were able to find that compared to some related genomes, coffee has not changed much,” said Sankoff, “whereas things like tomatoes and potatoes and some other related genomes have changed a lot more.”

Sankoff, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Mathematical Genomics, said he was surprised by the “relative conservatism” of the coffee genome.

U of O postdoctoral fellows Chunfang Zheng and Katharina Jahn were also involved in the study. The mathematicians used complex algorithms to sequence the genome.

The study, which was published in the journal Science, also provided insight on how caffeine is formed. Their findings suggest the enzymes in caffeine evolved independently in the plants that produce coffee, tea, and cocoa.

The sequencing of the genome was done in Paris, France and Illinois. Researchers from agencies, universities, and laboratories in other parts of the world also collaborated on the project.

This study provides vital information for the millions of people worldwide who depend on coffee to make a living, said Sankoff, such as coffee breeders and producers and food scientists.

It also opens up the possibility of developing more resilient plants. Climate change has altered the typically cool climate, putting the coffee plant in peril.

The hope is that scientists like Sankoff would be able to alter the coffee plant so it becomes more resistant to pests, heat, and droughts.

“Coffee Arabica has to grow in a cool place, on a mountain usually, and when you get this warming, huge tracts of land that were used for Arabica are becoming too warm,” he explained.

Rust infections of the plant’s leaves have also had a devastating effect on coffee growers, most of whom come from Central and South America.

The next challenge for Sankoff is sequencing the genome for Arabica coffee. The genome of the Arabica species is derived from both the Robusta and the eugenioides species of coffee, making it more complex.

“What we know about Robusta is going to help enormously for Arabica,” said Sankoff, “because we can build on the genome.”