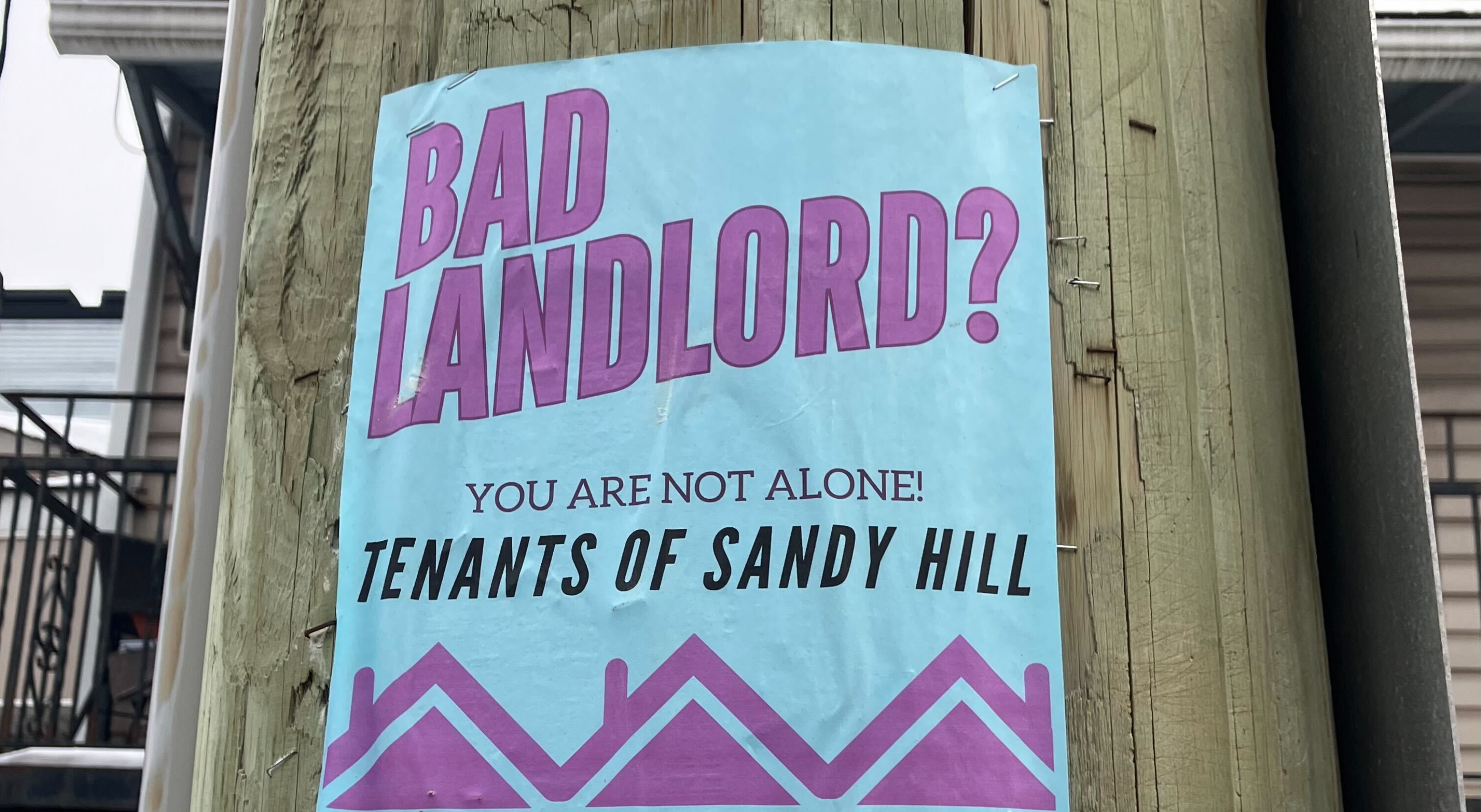

“Bad landlord? You are not alone!”

Residents of Sandy Hill seek to start a tenant union in the neighbourhood. The union, Tenants of Sandy Hill (TOSH), is a renters’ collective aiming to represent residents of the neighbourhood. TOSH had their inaugural meet-up on March 22, at the Happy Goat café on Wilbrod St.

Flyers have been stapled up on street lights and electrical posts around Sandy Hill from the TOSH, calling on tenants to unite against what they perceive as unfair treatment by landlords and property management companies. “Bad landlord? You are not alone!” says one poster in bright purple text, indicating renting residents to join TOSH. Another stapled handbill is aimed at tenants of buildings managed by Smart Living Properties (SLP), now known as Dwell. The handbill claims that SLP “has a history of exploiting students” and is contributing to the decline in affordable housing in the region.

Some of the inspiration for the creation of TOSH comes from other collectives in Ottawa, such as Bank Block Tenants and the Neighbourhood Organizing Centre. Bank Block Tenants is a grassroots collective of 11 tenants around Bank St. and Nepean. They have been actively challenging eviction by their property manager, Smart Living Properties.

The Fulcrum met up with Ashley Liza and Abel Arwaga, two founding members of Tenants of Sandy Hill. Arwaga highlighted some of the struggles that affect Sandy Hill residents, many of whom are international students, retirees or families. Arwaga noted that students, in particular, often struggle to assert their rights. “Students either don’t know that they can push back or they just don’t have the bandwidth because they’re just starting school or they’re just coming to a new city,” he explains.

Rather than focusing solely on advocacy or lobbying for policy changes, the group emphasizes community organizing as a means of building collective power. “We are not an advocacy group,” says Liza. Instead of advocating for specific policies or legislation TOSH is instead “interested in organizing and building power collectively.” Arwaga added that relying on legislative actions alone could be ineffective in upholding tenant rights.

“Unfortunately the current system doesn’t really favour tenants… The legal and arbitrations systems that are set up in place are very byzantine and extremely anti-tenant,” says Arwaga, referring to legislation around housing in Ontario. “Even the solutions proposed by local [and] provincial governments don’t often serve tenants,” Arwaga continues. “We might need to use these legal avenues in specific cases, as tactics, really we have to organize first and collectively, directly fight for our own interests. And even the rights that we do have, we kind of have to be collectively organized to enforce them .”

The housing challenges in Sandy Hill are part of larger concerns affecting housing in Ottawa. A Point-In-Time count report conducted by the city of Ottawa measured 2952 people experiencing homelessness, a 13% and 78% increase from 2021 and 2018 respectively.

TOSH members brought up concerns surrounding property managers creating renovations. “A lot of Sandy Hill houses are older, … if you keep living in the same place, they have the maximum increase,” says Arwaga in reference to provincial rent control measures on houses built prior to 2018, capping rent increases at 2.5%.

“But, if they renovate it … they can get a new tenant at a much higher price.” This practice of creating repairs with the goal of increasing rent prices has been dubbed “renoviction” or, when buildings face demolition, “demoviction”. The issue of “demovictions” was brought up by another tenant organization in Ottawa, Bank Block Tenants, to a city hall committee last December, alongside concerns of increased housing costs.

CityNews reports an average rent price of $2,012 in December 2024, representing a 3.2% decrease since the previous year. CityNews cites data from Urbanation, a real-estate consulting firm for the apartment industry and Rentals.ca a rental platform company.