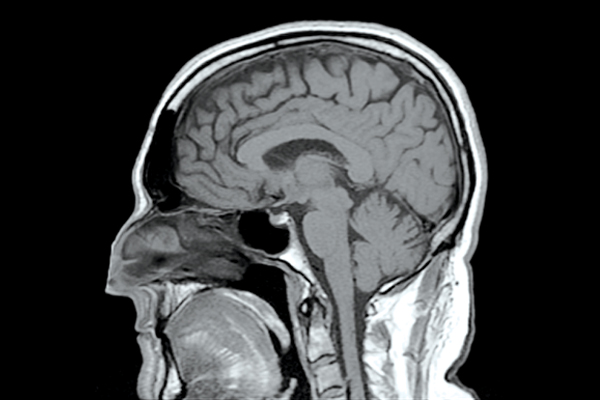

Researchers use brain scans for earlier detection and prevention

Photo:CC Reigh LeBlanc

Strokes are the third-leading cause of death in Canada, with over 14,000 people dying per year,” said Jeffery Perry, co-senior author of a new study that looks into how brain scans can help determine those who could be at risk of a stroke.

Perry is also an associate professor of emergency medicine and a research chair in emergency neurological medicine at the U of O, and a senior scientist in clinical epidemiology at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

U of O researchers George Wells, Dar Dowlatshashi, Grant Stotts, and Ian G. Stiell also partook in the study. The results were published in the American Heart Association journal, Stroke.

The project

Strokes occur when blood flow to the brain is restricted, resulting in oxygen loss. The researchers decided to look at the after-effects of transient ischemic attacks (TIA), or minor strokes that require hospitalization, for insight on fatal strokes. TIAs have been used traditionally as a predictor of stroke risk because major strokes often follow TIAs after a short period of time.

“We wanted to assess the use of CT scans with TIAs,” said Perry. “We knew their value as a diagnostic tool, but had never examined them as a way to help prevent future attacks.”

With this knowledge, the researchers administered a CT scan of TIA patients within 24 hours of the attack, seeing if they could predict whether the patient is at risk of another stroke, or when their symptoms will worsen.

They gave 2,028 TIA patients in hospitals all over Canada and the United States CT scans over a four-year period. The scans were analyzed to determine if there was new or old damage in the brain, and the similarities between patients.

The result

“We knew that the imaging would be an important preventative measure, but we never expected the magnitude of their importance,” said Perry.

The brain scans revealed that of the 2,028 patients, 814 (40.1 per cent) suffered brain damage due to ischemia, a lack of sufficient blood flow. These patients were 2.6 times more likely to have another stroke within 90 days.

The risk for stroke was also 5.4 times greater for those who had previously damaged brain tissue, and 4.9 times for those who had blood vessel damage, or microangiopathy. Those patients who exhibited all three symptoms were eight times more likely to suffer a stroke.

“During the 90-day period, and within two days after the initial attack, patients with acute ischemia and additional damage were more likely to have a subsequent stroke,” said Perry.

In total, 3.4 per cent of the people in the study group had a subsequent stroke within 90 days, however this number rose to 25 per cent of patients who displayed all three symptoms.

Perry said he and his team hopes their research will help people who suffer minor strokes to “receive complete investigation and maximum stroke management immediately.”

Canadians should expect to wait up to two weeks for further investigation of stroke-risk, according to Perry, however this could be too late for those patients whose CT scans revealed to be at a greater risk.

Physicians should be “more aggressive” in managing patients with TIA when previous tissue damage is present, he said.

What’s next?

The Canadian TIA score already classifies the severity of minor strokes, however the findings from the U of O researchers will be used to update the score classification system.

Most patients with TIA undergo CT scans, but Perry said this should be required for all patients, as the images have proven a crucial way to “help healthcare professionals identify damage patterns leading to worse symptoms or future, more harmful strokes.”

The researchers also hope to develop the use of CT scans in diagnosing strokes, said Perry, integrating them with the identification of other risk factors including age, hypertension, and diabetes.