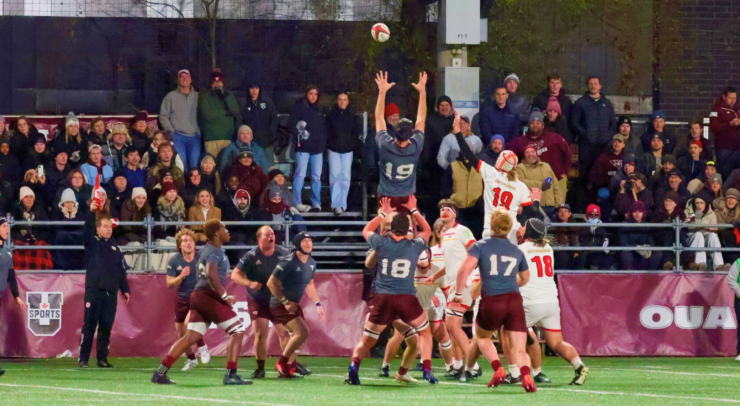

Photo by Tina Wallace

The Fulcrum is pleased to announce that it will host the 77th annual Canadian University Press national conference — or NASH 77, for short — in January 2015. It’s exciting to think that students at the University of Ottawa will be at the epicentre of the year’s gathering of eager and ambitious student journalists in such an uncertain time for the media industry.

But with great power (if you want to call it that) comes great responsibility.

It may now be more crucial than ever for young people to really analyze their media consumption. While these types of conferences are primarily focused on the working journalist, they also draw attention to the state of Canadian media as a whole. It’s this state that should be in the mind of any critical thinker enrolled in a post-secondary school in one way or another.

That’s not to say that every university and college student should spend their days rigorously analyzing and critiquing every newspaper and magazine on the rack — those enrolled in media studies courses will have more than enough of that to go around — but we are living in an age and culture in which people have become more and more focused on the way they consume goods and resources, and the media should be no exception.

The media industry is certainly in a “transitional period,” as it’s described by journalism professors and other industry veterans trying their hardest not to shatter the dreams of aspiring reporters. But there is much more to it than that. The changing shape of the media affects the consumer just as much as, and perhaps even more than, the practitioner.

The conception that journalism is dying is rather misguided. Sure, there’s not as much money in it than there was some time ago — not that the average news reporter was ever really rolling in it — but journalism itself is in fact more alive than ever. At the same time that newsrooms are becoming smaller and smaller, each slash to budgets and jobs more disconcerting to their employees than the last, the media market is also becoming more saturated. Citizen journalism and independent publishing, particularly on the web, is thriving (again, not necessarily in a financial sense). And there’s no question that mobile technology and online culture continue to have a profound impact on the way the news is produced, distributed, and consumed. News items from thousands of publications all over the world are now available to you while you’re sitting in the library, on the bus, on the toilet, or wherever it is you do your quality reading — and, for the most part, it’s completely free.

That means more options, which means more perspectives, which means more content and carriers to understand. It means recognizing not only what each publication is telling you about, but why it’s telling you about it. It means you’re in control of what you read and think about more than ever before.

Here in Ottawa, the media and its consumers are additionally shaped by the city’s political landscape. People from all across Canada turn their attention here regarding national issues. Reporters are all over Twitter, and so are politicians. It’s now easier than ever to make your voice heard. All it can take is fewer than 140 characters to interact with a politician or a news organization, and perhaps have your thoughts shared with hundreds or thousands more.

Social media is perhaps the most complicated form of media there is, though many people who use sites like Twitter and Facebook likely don’t think about it as such at all. But what it comes down to is a constant, steady stream of news from the widest variety of sources available. Social media is, in an oblique way, the greatest source of citizen journalism. So, who do you trust more: the people or the pros?

Bernard Cohen delivered the timeless quote that the media “may not be successful much of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling its readers what to think about.” Not only is it important to think about the social, political, and cultural issues that the media presents, but it’s also important to think about the media itself that we consume throughout our daily lives — whatever form it takes.

editor@thefulcrum.ca