Faculties must teach students to seek experience outside of their major

It’s back to school time once again, but many people may still be unsure about what classes they should be taking. Whether they’re just starting out or changing their major, all students will be looking carefully at where that major is likely to get them in five years, 10 years, and beyond.

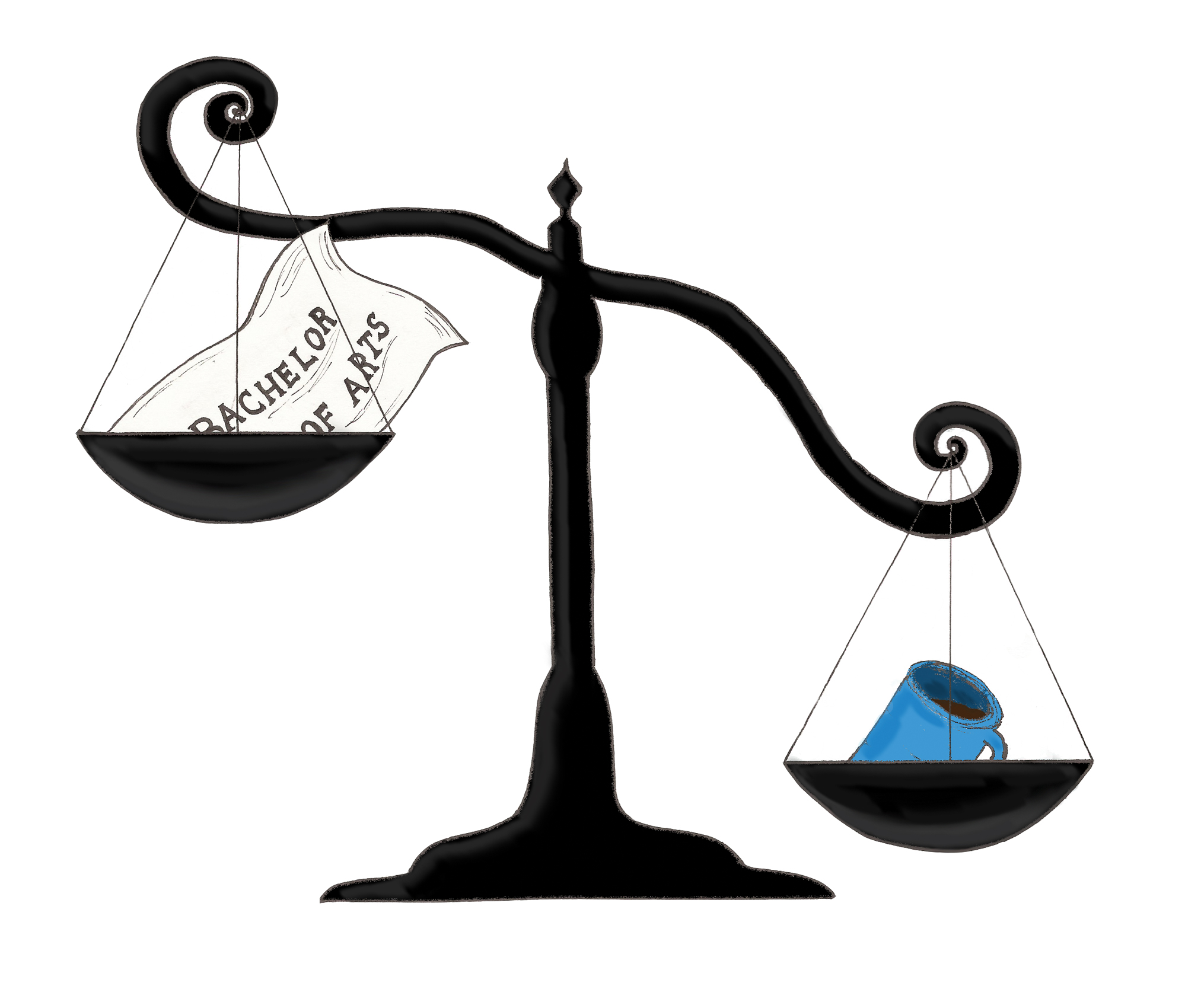

A recent study from the University of Ottawa brings good news for traditionally harassed arts majors, finding that students from all disciplines can make a good wage after graduation.

And that has major implications, effectively proving that universities and society at large should be encouraging students to choose the majors that really interest them—not what they think will net them the biggest paycheck.

But knowing that you can make money is only one factor in choosing a major. Another thing students must be taught is that all academic disciplines can lead to successful careers across many disciplines—that they aren’t forever trapped in their degree’s “traditional” career path.

A list from the physics honor society provides examples of physics majors who took surprising career paths—including patent lawyer, philosopher, and “imagineer”. A similar list from Portland University reveals that art history majors found similarly diverse careers, including one finance coordinator at a science museum.

Luckily, there are plenty of steps that universities can take to help students realize that their potential may lie across multiple fields. For example, they can organize events that encourage students from different disciplines together to work on unorthodox problems.

Of course, there are groups on campus doing this already. A science lab operated by U of O professor Andrew Pelling, which has garnered media attention for its work growing a human ear in an apple, includes “artists in residence” on its staff, as well as an anthropologist.

The social entrepreneurship club Enactus uOttawa has a program where it sticks two business students and two engineers in a room and gets them to combine their two very different sets of expertise to solve a single problem.

And this is exactly the right idea—taking several forms of knowledge and throwing them together to find innovation at the point of intersection.

Universities can continue to foster this kind of environment by continuing to promote events and groups centered on exposing students to the knowledge cultivated in disciplines outside their area of study.

Don’t think this will carry any weight after graduation? Take a look at Shopify, the Ottawa-based tech giant that flaunts go karts in its main offices. Most of their job openings are for coding, but not all of them. Finance intern, German translator, and “Wearer of many hats” are also listed in their careers section.

As technology advances and the world becomes more integrated, companies and organizations will become less insular, and will require a greater diversity of creative talent—U of O students will only build stronger careers by fuelling their curiosity and looking beyond their textbook.