Reform of SFUO constitution necessary to engage more student voters

Illustration by Tina Wallace

Stefanie Di Domenico is a fourth-year international development (DVM) student at the University of Ottawa studying in the co-operative education program. She is involved in the university community, is passionate about student politics, and was in favour of separating the international development program from the larger Political, International, and Development Studies Student Association (PIDSSA), which was put to a referendum in the most recent Student Federation of the University of Ottawa (SFUO) election in early February. So, why wasn’t she allowed to vote?

At the time of the election someone in Di Domenico’s family experienced health issues. She took the winter semester off of school to be home with her family, and was granted permission by the co-op office to do so without any effect on her standing within the co-op program or her academic sequence. But by taking a semester off, regardless of her reason, she was deemed ineligible to vote both in the SFUO elections and in the DVM referendum.

Di Domenico’s story is just one of many cases of students who have been faced with unfair barriers between their participation in university elections.

The SFUO constitution states that its members — students allowed to vote come election time — are “full-time and part-time undergraduate students at the University of Ottawa.” Seems pretty black and white — you go to school here, you can vote.

But the situation becomes more complex with students, like Di Domenico, whose status as a member of the SFUO isn’t clearly defined.

Students studying in a co-operative education program also fall into this grey area. These students, beginning after their second year of studies, alternate between work and school terms for the rest of their degrees. When co-op students have a work term, they are not expressly listed as members of the SFUO, unless they are also taking part-time courses.

During the last election this meant that these co-op students were left off the voter eligibility lists. Many co-op students were turned away at voter booths because of this, while others who persisted were given various haphazard solutions. Some had their votes put into separate envelopes, some had to go to the office of Melanie Large, the chief electoral officer (CEO), personally and have someone from the office escort them to the voting booth, while others were told they could vote for executive candidates, but not for the referendums.

The problem seems to be the SFUO constitution’s outdated and vague language. In an email to Di Domenico, Large stated that she was denied a vote because “only members of the SFUO at the time of the election have the right to present themselves as candidates and/or to vote in the election.” This is because, as per section 2.2.1 and 2.2.2 of the SFUO constitution, students are only recognized as members of the SFUO when they are taking classes full-time or part-time and paying membership fees to the SFUO.

But there are no clear rules in the constitution surrounding exceptional cases like Di Domenico’s, or any mention of the eligibility of co-op students.

In an email to the Fulcrum, Large stated that “It was brought to my attention that there was an issue that co-op students do not pay ancillary fees, i.e., they only pay their co-op fees. They are therefore not considered members of the SFUO.” But this contradicts multiple accounts from co-op students who claim it was only through Large’s intervention that they were able to vote, albeit in separated envelopes.

When the guidelines for eligibility aren’t clear, when students have to argue with SFUO employees at the ballot box just to get their vote to count, how can we blame student apathy for low voter turnout?

The reason why Di Domenico was deemed ineligible to vote, along with the more than 650 students currently participating in the work terms for their co-op degrees, was because she wasn’t currently a paying member of the SFUO.

Even though Di Domenico, and almost all of the students enrolled in co-op, will return to school in the summer semester and in next year’s winter term, both of which fall under the jurisdiction of the new SFUO executive that was elected in February, she wasn’t allowed to participate in the democratic process.

She was also not allowed to vote in the DVM referendum and the school-wide referendum concerning the implementation of a General Assembly, both of which will have a lasting impact on her academic career at the U of O, well beyond the winter semester she didn’t pay fees for.

Di Domenico was told by an SFUO employee that allowing her vote would be unconstitutional because as an unregistered and non-paying member of the SFUO, there was no guarantee she would return to school next year. The rationale behind this is that only paying members are guaranteed to return to school next year.

But doesn’t this risk apply to every single student studying at the U of O? Any student, including those enrolled during this winter semester, could at any time drop out of school. Di Domenico is no less likely to come back to school next year than someone who didn’t have to unregister for classes because of family health issues.

Perhaps even more troubling is that while she was told by the CEO that “there is no room on the interpretation of this rule,” the SFUO constitution doesn’t always require enrolment for membership.

According to section 2.2.5 of the constitution, “a person who was an individual member for the whole of the winter term shall be deemed an individual member for the subsequent summer term. Such a member, unless currently registered at the University of Ottawa, shall not be required to pay the Federation membership fee.”

The rationale behind this stipulation seems obvious: Students are still students over their summer breaks, and should be entitled to the same rights and services as they are during the school year. So why isn’t this same reasoning applied to co-op students? Or to a student who had to take a semester off for personal reasons?

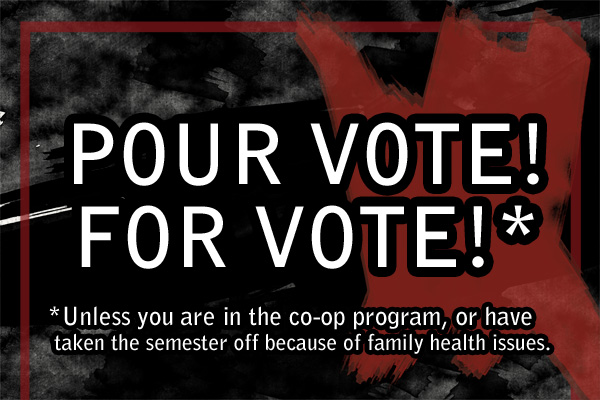

During the SFUO election, time and money was spent by the SFUO on an ad campaign that encouraged students to vote. You might have recognized it by a giant V and the inspiring words, “For Voice For Vote!” Such efforts imply that it is the fault of students that voter turnout rates remain abysmally low — 11.6 per cent turnout this year, up from 10 per cent last year — when in reality no efforts are being made by the SFUO to make the elections more inclusive and accessible to students.

Not one SFUO executive candidate mentioned election reform during their pre-election debates this year, or ever addressed the issue of co-op student ineligibility for voting in their campaigns.

Online voting was removed in 2010 because of complications and fraud allegations that led to a refusal by the U.S. company that ran the online voting component to work with the student union. But since e-voting was eliminated, voter turnout has been cut in half. Efforts to bring it back during this year’s election were as non-existent as the help Di Domenico has received in making her voice heard.

Luckily for her, the DVM referendum passed without her vote. But her situation raises a glaring problem that must be addressed if voter turnout is ever expected to rise to respectable levels again.

The SFUO constitution needs to be reformed to give all students, including those in co-op and those with exceptional circumstances, the same democratic rights. But broader electoral reform is also needed to enable students to engage more easily in student democracy. Only then will we achieve better voter turnout, and a form of student government that more resembles democracy.