Mental health practices in sports

Maclaine Chadwick | Fulcrum Staff

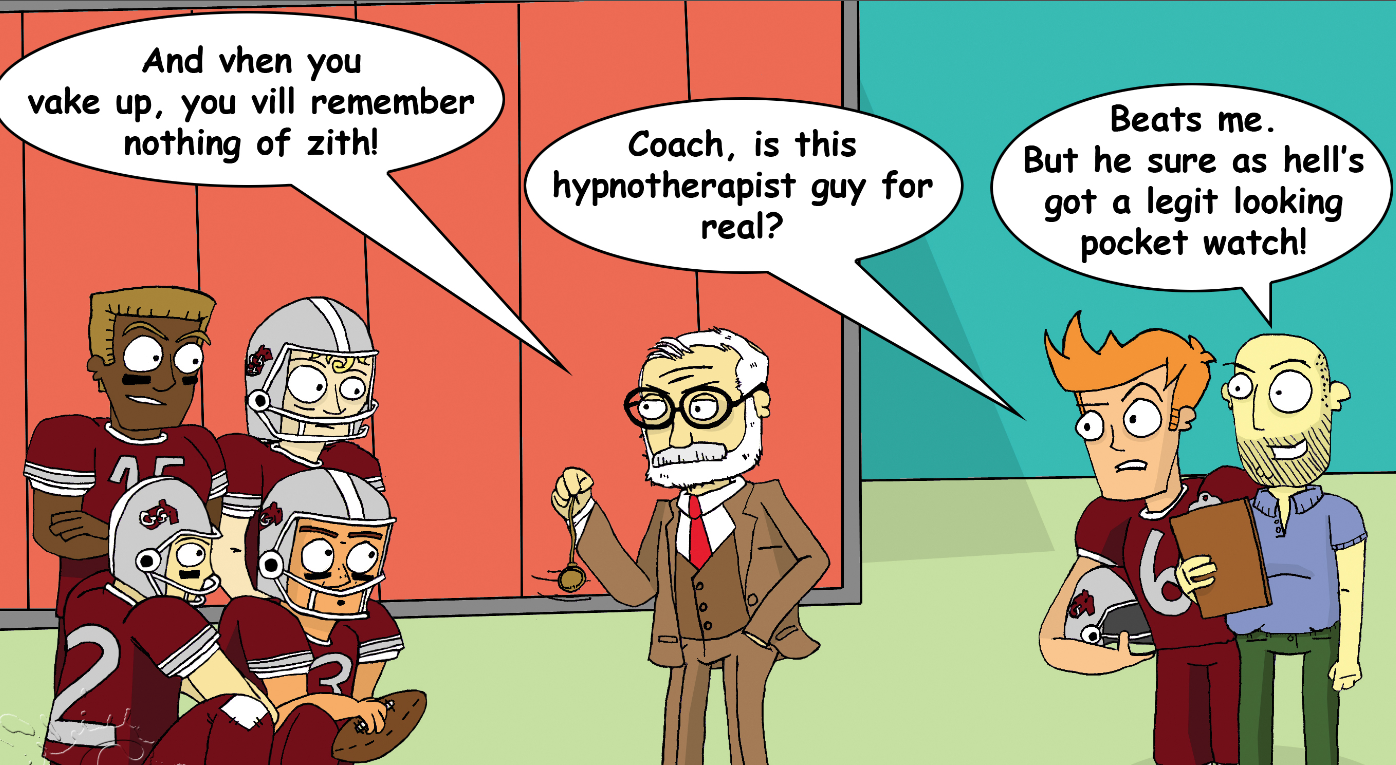

Illustration by Devin Beaugard

There is more to athletic ability than being physically strong, fast, or agile. Mental health plays an important role in an athlete’s performance, as they face different pressures and fears every time they compete.

There are certain skills athletes cannot work on in a gym. Confidence, motivation, leadership, and teamwork, for example, can all affect sports performance. In some cases, coaches will employ a psychologist or hypnotherapist to harness an athlete’s inner power. If that all sounds like a load of baloney to you, keep in mind that these practices have been employed by world class athletes like Tiger Woods, Roger Federer, and Reggie Jackson.

Sports psychology

If you were a basketball fan at the University of Ottawa last year, you will remember last winter’s game against the Laurentian University Voyageurs, in which all-star U of O guard Warren Ward injured his knee and tore his anterior cruciate ligament, commonly known as the ACL.

After the injury, Ward began seeing a sports psychologist. “It was something I wanted to do on my own,” he said in an interview with the Fulcrum. “We would meet with [the psychologist] before the season once a week and we would come up with different things [to work on]. I thought he was good at what he was talking about so I continued to see him.”

In his book The Psychology of Exercise: Integrating Theory and Practice, Curt Lox describes the rise of fitness psychology as riding on the heel of the fitness craze of the 1980s. The idea was borne out of the new found emphasis on body image and “thin is in” philosophy, but its roots go much farther back. The first course in sports psychology was offered in 1925 after late-nineteenth-century researchers became curious about the nature of athletes in competition.

These days, sports psychologists play a number of roles, such as motivating teams before games and helping athletes deal with injury setbacks or performance anxiety.

Although Ward doesn’t credit his healing completely to sports psychology, he does think the process was helpful.

“It just made it easier to get over. I had my week where I was depressed and after that I just decided that I’m not going to quit,” he said.

Ward has found sports psychology helpful off the basketball court as well.

“Most of it has to do with me as a leader and as a teammate … and how to deal with some of the stuff that a lot of people don’t know about that goes on with me or playing on this team, or just me as a person.”

Despite the obvious benefits of sports psychology, many people still view it with skepticism.

“I think a lot of people look down upon it and think, ‘Oh, so you’re seeing a shrink?’” Ward said. “I have no shame about it. I think it helped me. It drove me a little crazy for a while, but it did help me … You have to sacrifice certain things if you want to change something that you think is wrong in your life.”

Sports hypnosis

Louise Goddard is a hypnotherapst, but no, she isn’t going to swing a pendulum in your face and tell you you’re getting sleepy.

“I don’t think anybody really does that now,” she laughed.

In a Skype interview with the Fulcrum, Goddard debunked some myths about hypnosis and outlined how athletes can benefit from it.

“One of the most popular misconceptions is that I have power over the client, and that’s not really what happens. A hypnotist is only a guide, and you basically tell me what you want, what you want to think or feel in certain situations,” explained Goddard.

Hypnotherapy works by allowing a therapist to tap into your subconscious and help you convince yourself that you are reliving an empowering situation from your past—one where you were feeling on top of the world.

“Your subconscious mind doesn’t know the difference between what is vividly imagined and what is really going on,” explains Goddard. “So if you can harness that power and strength of really imagining a certain event that was really empowering, then your subconscious doesn’t know whether you are remembering or whether it is really happening.”

The memory of a time where you were your strongest can be accessed if you train your mind to associate it with a gesture called an anchor, which can be as simple as pressing your thumb and index finger together.

“When you’re running and you get to that point where you think ‘Oh, that’s enough for today,’ but you really don’t want that to happen, then you can regenerate those feelings [of empowerment] by firing off that anchor. Everything will change; your breathing will even out, and your pace will lengthen,” said Goddard.

This process is not only useful as a physical aid, but also as a way to help athletes break through mental barriers. Louise Goddard described a past client, a tennis player, who feared injury and wasn’t performing at his top level. Using anchoring, he found he was able to go for shots that he otherwise wouldn’t attempt. Another of Goddard’s clients, a triathlete, used anchoring to perform at a level she had performed at before an injury, and was able to race with more confidence.

Unfortunately, seeing a psychologist or hypnotherapist may not be the only thing that’s keeping you from being the next Sidney Crosby or Michael Phelps—physiology and physical training are still the primary components of athleticism. But if you are on the cusp of achieving your own athletic goals, or struggling to overcome a fear or anxiety, maybe a visit to the psychologist or a quick NLP session is just what you need.

“When we want to achieve anything, we have to achieve it in our minds first,” said Goddard. “Anything has to be imagined first.”