[notdevice]

Often times torture techniques are discussed and debated in classrooms using hypotheticals. But for Jesse Colautti, a visit to a former Stasi prison in Berlin put a very real face and life to a cruelty that persists today.

Photos by Jesse Colautti, Emily Niles, and Camille Tremblay

Karl-Heinz Richter was 17 when he was first tortured at the hands of the Stasi, the Ministry of State Security of the former German Democratic Republic. A resident of East Berlin when the wall was put up in 1961 to divide the two halves of the city, Richter was part of a plot to escape the German Democratic Republic (GDR) on trains passing through Berlin on their way into the West. Seventeen of his friends successfully leapt onto trains, most of whom went on to attend university in the West and lead successful careers. But Richter wasn’t so lucky.

Attempting to escape on board a train destined for Paris on the night of Jan. 30, 1964, Richter leapt onto the steps of the last car. But as his fingers gripped cold metal, his legs couldn’t make it onto the steps. Eventually his grip gave way and he slipped back into East Berlin, into more than three years of solitary confinement at the hands of the Stasi, into a future haunted by the devastatingly invasive effects of torture.

To this day, when Richter closes his eyes he can see the dwindling red lights of the train as they vanished into a future that he would never know.

My tour guide

Fifty years after his failed escape attempt, I meet Karl-Heinz Richter while in Berlin for a summer field research course to study the Cold War. He greets our class while we arrive at the eerily well-preserved gates of the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial, the central Stasi prison during the years of the GDR. The only thing we know about him is that he’s our tour guide.

He begins by discussing his early years in the GDR. Within the former authoritarian state, all resistance to the state was forbidden. Public signs of protest were met with zero tolerance by the police; higher education was reserved only for members of the socialist party youth group, the Free German Youth; and one in seven citizens was either a voluntary or coerced informant for the Stasi.

“I didn’t want to be part of this,” Richter says as he walks us past the concrete outer walls of the prison topped by barbed wire. “Three of my friends had been shot and killed at the wall trying to escape. I couldn’t have this be my country.”

Richter then leads us to steps that plunge beneath a large, red brick building into a dark corridor below. “This is where I spent most of my first six months in prison,” he says. “It is called the submarine.”

Broken and imprisoned

After Richter’s fingers slipped off the Paris-bound train, he was left face down on the tracks with very few options for survival left. He was surrounded by GDR guards who somehow hadn’t seen him up to this point, but who were trained and willing to shoot him. His only option was to get off the elevated tracks as soon as possible, so he sprinted towards the edge of the tracks and, without looking, leapt over the railing and into the East Berlin street below.

The drop was more than seven metres, and upon impact with the asphalt Richter instantly broke both his legs and his right wrist, and was knocked unconscious. He came to minutes later and dragged his broken body two kilometres back to his parents’ home, where he was arrested by the Stasi a week later and brought to Berlin-Hohenschönhausen prison. He was not given any medical treatment for his injuries during the six months he spent there.

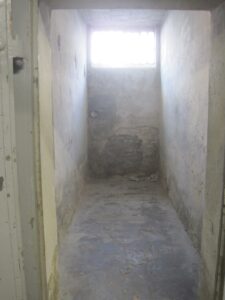

Richter leads our group through a long passage of cells to one particular door on the right. Inside is an eight-by-four-foot cell devoid of any furnishing, walled in by bricks covered in cracking white paint. “This is my old cell,” he says. “There used to be a bucket in the corner for a toilet and a wooden plank bed at the back to sleep on, but it still looks and smells as it did then.”

Richter tells us how inmates would have to go months without a shower, how the amount of filth on his body became so unbearably itchy that he became covered with bloody sores from scratching too deep. He tells us that many inmates died after their sores became infected.

“I remember the first time I peed into my hands to clean myself,” he recalls. “It was the only way to keep my wounds from becoming infected, but it was the most degrading thing I had ever done.”

Torture

Richter leads us next into a building farther back into the grounds of the prison. We descend to the lowest level and walk to the door of a cell covered in black padding. Inside there is no window or light of any kind, but there is just enough light from the outside corridor to see faint patterns of torn upholstery on the walls, ripped up by fingernails decades ago. The stench is almost unbearable.

As Richter begins to explain the dark room, he pauses for a moment. His eyes close, his shoulders tense, and he leans his head away from our group. “I still find it difficult to be here.”

The Stasi’s methods of torture were intricately planned, precisely designed to test the physical and mental weaknesses of each inmate. As an attempted deserter, and worse, someone who was thought to have assisted others in escape, Karl-Heinz Richter was subjected to the full extent of the Stasi’s methods.

There was the physical torture. Five times he was put into a cell three-quarters filled with water for a 72-hour period. Sleeping or sitting would mean drowning. This for a man with two broken legs.

There were the dozens of nights he was kept up by guards beating him for turning over in his sleep, or when they would turn on the lights periodically throughout the night to make sure he was never fully rested.

But even more disturbing was the mental torture. The night he was told he was to be executed in the morning, when he didn’t sleep at all as he heard the guards outside laughing about how they were going to enjoy killing him, only to have a guard come into his cell in the morning with breakfast, laughing that it was all a joke.

Or the endless hours he spent knocking on his cell walls in Morse code to talk to Monika in the cell next to him, pouring out his fears and desires in excruciatingly slow progress for weeks, only to be told later that Monika wasn’t in fact a prisoner or a real person at all, but a series of Stasi agents trying to get information from him.

“They hated me, which meant they used any sign of disobedience or resistance from me as an excuse to send me to the dark room,” says Richter.

“Here they would keep me in complete darkness for week-long stretches, in which the only light I would see was from when they dropped in a plate of gruel or cup of water.”

He explains how once, in an attempt to reach the water, he knocked the cup over onto the floor. He had no other option but to lick up the water off of the filth- covered cement. “I can still taste that floor today.”

Justifying cruelty

A memory keeps replaying itself in my mind as Richter leads us away from the dark room. It is of a class discussion I had a year earlier in a counter-terrorism class. We’re discussing torture, its justifications, and how it’s used in today’s war on terror.

The major justification behind it is that terrorism is an exceptional threat, with such unimaginable consequences that it must be fought with whatever tactics possible. I hear my own voice rehashing the hypothetical ticking bomb scenario, arguing that in the case of a known and immediate threat, the treatment and well-being of one terrorist should not be prioritized over the lives of thousands, or even millions, of people in danger.

It is a form of this argument that is used to justify the “enhanced interrogation” techniques used at Guantanamo Bay during the last two decades—when techniques such as sleep deprivation and water boarding have allegedly been used in the name of preventing another 9/11. A knot grows in my stomach as I can hear my own voice justifying such evils in the name of utilitarianism.

The legacy of torture

Richter leads us out of the basement, through a strikingly bright corridor of laminate flooring and fluorescent light bulbs, into a seemingly normal office with a large wooden desk, old fashioned green telephone, two comfortable upholstered chairs at one end of the room, and one small meek wooden chair at the other.

“This was the room I was interrogated in,” he says.

Richter sits, and our class crowds around him noticeably relieved, believing the worst of his story to be over.

It is here Richter tells us about the most devastating part of his story: his release. He tells us how after six months in this prison, due to pressure put on the GDR government from sympathizers in the West who had heard of his story, he was released to a hospital. After 18 months and 15 surgeries he was allowed back in to East Berlin, “a symbol of the GDR’s humanity.”

He attempted to regain a normal life, but this was cut short on a night in November 1967. His father, who Richter believes hadn’t recovered from the shock of what happened to his son, died in his arms of a heart attack. “It broke me,” he says. “I climbed up onto my roof and yelled, ‘You did this, you killed him.’”

Within weeks of this outburst he was brought back to the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen prison for again defying the state. Here he would spend another two and a half years in solitary confinement, subject to much of the same treatment as before.

When he finally got out for good in 1970, he tried again to start a normal life. He got married and had a daughter. Eventually, the GDR gave up trying to turn him into a loyal citizen and approved his application to leave to the West.

But before this, his wife was arrested and brought to the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen prison, and his daughter was taken away from him.

By this point our whole group is in tears, and Richter takes a long pause before telling us what happened next.

“My wife was beautiful, a real looker. But when she was in jail the guards forced themselves on her,” he says.

“She couldn’t get her mind over what happened in prison and how she was treated. When she got out of prison, I told her what happened to her daughter. It was then she lost touch of reality.

“After two and a half years my daughter was returned to us, and we were allowed to leave to the West. But my wife’s soul was broken.”

His wife has spent most of her adult life in a psychiatric hospital, while his daughter has not spoken to him in 15 years—the pain of the memories he stirs within her is too much.

Richter concludes the tour at a small enclosed courtyard. High walls loom over us, and our view of the sky is disturbed by metal bars.

“This is the only place we were allowed to get fresh air,” says Richter.

“I used to look up at the sky and see birds as a symbol of freedom. They were all I saw of an outside world. They were free and I was not.”

Facing my own guilt

As we say our goodbyes to Richter, my head pounds as I am brought back to that classroom a year ago. I hear the way I’m discussing the threat of terrorism. It is not unlike the way Richter has told me his Stasi interrogators discussed the threat of desertion in the GDR—evils that must be avoided at all costs.

But I understand now what I didn’t then: justifying human cruelty in the name of preventing some unimaginable evil precludes the effectiveness of any other method to prevent it. In hindsight, there were many other ways the GDR government could have dealt with the fleeing of its citizens to the West other than building a wall or torturing its citizens. There are ways we can stop terrorism today without using torture. There must be.

As I walk away from Richter and back into the streets of Berlin I am left with a guilty and sick feeling of responsibility. Even in a classroom, I will never defend torture again.

The bright future that once eluded Karl-Heinz Richter by inches as he stared up at the quickly receding red lights of a train bound for Paris has become my responsibility to share. It is the cost of torture.[/notdevice][device]

Often times torture techniques are discussed and debated in classrooms using hypotheticals. But for Jesse Colautti, a visit to a former Stasi prison in Berlin put a very real face and life to a cruelty that persists today. (put on top of first photo)

Photos by Jesse Colautti, Emily Niles, and Camille Tremblay

Karl-Heinz Richter was 17 when he was first tortured at the hands of the Stasi, the Ministry of State Security of the former German Democratic Republic. A resident of East Berlin when the wall was put up in 1961 to divide the two halves of the city, Richter was part of a plot to escape the German Democratic Republic (GDR) on trains passing through Berlin on their way into the West. Seventeen of his friends successfully leapt onto trains, most of whom went on to attend university in the West and lead successful careers. But Richter wasn’t so lucky.

Attempting to escape on board a train destined for Paris on the night of Jan. 30, 1964, Richter leapt onto the steps of the last car. But as his fingers gripped cold metal, his legs couldn’t make it onto the steps. Eventually his grip gave way and he slipped back into East Berlin, into more than three years of solitary confinement at the hands of the Stasi, into a future haunted by the devastatingly invasive effects of torture.

To this day, when Richter closes his eyes he can see the dwindling red lights of the train as they vanished into a future that he would never know.

Fifty years after his failed escape attempt, I meet Karl-Heinz Richter while in Berlin for a summer field research course to study the Cold War. He greets our class while we arrive at the eerily well-preserved gates of the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial, the central Stasi prison during the years of the GDR. The only thing we know about him is that he’s our tour guide.

He begins by discussing his early years in the GDR. Within the former authoritarian state, all resistance to the state was forbidden. Public signs of protest were met with zero tolerance by the police; higher education was reserved only for members of the socialist party youth group, the Free German Youth; and one in seven citizens was either a voluntary or coerced informant for the Stasi.

“I didn’t want to be part of this,” Richter says as he walks us past the concrete outer walls of the prison topped by barbed wire. “Three of my friends had been shot and killed at the wall trying to escape. I couldn’t have this be my country.”

Richter then leads us to steps that plunge beneath a large, red brick building into a dark corridor below. “This is where I spent most of my first six months in prison,” he says. “It is called the submarine.”

Broken and imprisoned

After Richter’s fingers slipped off the Paris-bound train, he was left face down on the tracks with very few options for survival left. He was surrounded by GDR guards who somehow hadn’t seen him up to this point, but who were trained and willing to shoot him. His only option was to get off the elevated tracks as soon as possible, so he sprinted towards the edge of the tracks and, without looking, leapt over the railing and into the East Berlin street below.

The drop was more than seven metres, and upon impact with the asphalt Richter instantly broke both his legs and his right wrist, and was knocked unconscious. He came to minutes later and dragged his broken body two kilometres back to his parents’ home, where he was arrested by the Stasi a week later and brought to Berlin-Hohenschönhausen prison. He was not given any medical treatment for his injuries during the six months he spent there.

Richter leads our group through a long passage of cells to one particular door on the right. Inside is an eight-by-four-foot cell devoid of any furnishing, walled in by bricks covered in cracking white paint. “This is my old cell,” he says. “There used to be a bucket in the corner for a toilet and a wooden plank bed at the back to sleep on, but it still looks and smells as it did then.”

Richter tells us how inmates would have to go months without a shower, how the amount of filth on his body became so unbearably itchy that he became covered with bloody sores from scratching too deep. He tells us that many inmates died after their sores became infected.

“I remember the first time I peed into my hands to clean myself,” he recalls. “It was the only way to keep my wounds from becoming infected, but it was the most degrading thing I had ever done.”

Torture

Richter leads us next into a building farther back into the grounds of the prison. We descend to the lowest level and walk to the door of a cell covered in black padding. Inside there is no window or light of any kind, but there is just enough light from the outside corridor to see faint patterns of torn upholstery on the walls, ripped up by fingernails decades ago. The stench is almost unbearable.

As Richter begins to explain the dark room, he pauses for a moment. His eyes close, his shoulders tense, and he leans his head away from our group. “I still find it difficult to be here.”

The Stasi’s methods of torture were intricately planned, precisely designed to test the physical and mental weaknesses of each inmate. As an attempted deserter, and worse, someone who was thought to have assisted others in escape, Karl-Heinz Richter was subjected to the full extent of the Stasi’s methods.

There was the physical torture. Five times he was put into a cell three-quarters filled with water for a 72-hour period. Sleeping or sitting would mean drowning. This for a man with two broken legs.

There were the dozens of nights he was kept up by guards beating him for turning over in his sleep, or when they would turn on the lights periodically throughout the night to make sure he was never fully rested.

But even more disturbing was the mental torture. The night he was told he was to be executed in the morning, when he didn’t sleep at all as he heard the guards outside laughing about how they were going to enjoy killing him, only to have a guard come into his cell in the morning with breakfast, laughing that it was all a joke.

Or the endless hours he spent knocking on his cell walls in Morse code to talk to Monika in the cell next to him, pouring out his fears and desires in excruciatingly slow progress for weeks, only to be told later that Monika wasn’t in fact a prisoner or a real person at all, but a series of Stasi agents trying to get information from him.

“They hated me, which meant they used any sign of disobedience or resistance from me as an excuse to send me to the dark room,” says Richter.

“Here they would keep me in complete darkness for week-long stretches, in which the only light I would see was from when they dropped in a plate of gruel or cup of water.”

He explains how once, in an attempt to reach the water, he knocked the cup over onto the floor. He had no other option but to lick up the water off of the filth- covered cement. “I can still taste that floor today.”

Justifying cruelty

A memory keeps replaying itself in my mind as Richter leads us away from the dark room. It is of a class discussion I had a year earlier in a counter-terrorism class. We’re discussing torture, its justifications, and how it’s used in today’s war on terror.

The major justification behind it is that terrorism is an exceptional threat, with such unimaginable consequences that it must be fought with whatever tactics possible. I hear my own voice rehashing the hypothetical ticking bomb scenario, arguing that in the case of a known and immediate threat, the treatment and well-being of one terrorist should not be prioritized over the lives of thousands, or even millions, of people in danger.

It is a form of this argument that is used to justify the “enhanced interrogation” techniques used at Guantanamo Bay during the last two decades—when techniques such as sleep deprivation and water boarding have allegedly been used in the name of preventing another 9/11. A knot grows in my stomach as I can hear my own voice justifying such evils in the name of utilitarianism.

The legacy of torture

Richter leads us out of the basement, through a strikingly bright corridor of laminate flooring and fluorescent light bulbs, into a seemingly normal office with a large wooden desk, old fashioned green telephone, two comfortable upholstered chairs at one end of the room, and one small meek wooden chair at the other.

“This was the room I was interrogated in,” he says.

Richter sits, and our class crowds around him noticeably relieved, believing the worst of his story to be over.

It is here Richter tells us about the most devastating part of his story: his release. He tells us how after six months in this prison, due to pressure put on the GDR government from sympathizers in the West who had heard of his story, he was released to a hospital. After 18 months and 15 surgeries he was allowed back in to East Berlin, “a symbol of the GDR’s humanity.”

He attempted to regain a normal life, but this was cut short on a night in November 1967. His father, who Richter believes hadn’t recovered from the shock of what happened to his son, died in his arms of a heart attack. “It broke me,” he says. “I climbed up onto my roof and yelled, ‘You did this, you killed him.’”

Within weeks of this outburst he was brought back to the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen prison for again defying the state. Here he would spend another two and a half years in solitary confinement, subject to much of the same treatment as before.

When he finally got out for good in 1970, he tried again to start a normal life. He got married and had a daughter. Eventually, the GDR gave up trying to turn him into a loyal citizen and approved his application to leave to the West.

But before this, his wife was arrested and brought to the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen prison, and his daughter was taken away from him.

By this point our whole group is in tears, and Richter takes a long pause before telling us what happened next.

“My wife was beautiful, a real looker. But when she was in jail the guards forced themselves on her,” he says.

“She couldn’t get her mind over what happened in prison and how she was treated. When she got out of prison, I told her what happened to her daughter. It was then she lost touch of reality.

“After two and a half years my daughter was returned to us, and we were allowed to leave to the West. But my wife’s soul was broken.”

His wife has spent most of her adult life in a psychiatric hospital, while his daughter has not spoken to him in 15 years—the pain of the memories he stirs within her is too much.

Richter concludes the tour at a small enclosed courtyard. High walls loom over us, and our view of the sky is disturbed by metal bars.

“This is the only place we were allowed to get fresh air,” says Richter.

“I used to look up at the sky and see birds as a symbol of freedom. They were all I saw of an outside world. They were free and I was not.”

Facing my own guilt

As we say our goodbyes to Richter, my head pounds as I am brought back to that classroom a year ago. I hear the way I’m discussing the threat of terrorism. It is not unlike the way Richter has told me his Stasi interrogators discussed the threat of desertion in the GDR—evils that must be avoided at all costs.

But I understand now what I didn’t then: justifying human cruelty in the name of preventing some unimaginable evil precludes the effectiveness of any other method to prevent it. In hindsight, there were many other ways the GDR government could have dealt with the fleeing of its citizens to the West other than building a wall or torturing its citizens. There are ways we can stop terrorism today without using torture. There must be.

As I walk away from Richter and back into the streets of Berlin I am left with a guilty and sick feeling of responsibility. Even in a classroom, I will never defend torture again.

The bright future that once eluded Karl-Heinz Richter by inches as he stared up at the quickly receding red lights of a train bound for Paris has become my responsibility to share. It is the cost of torture.[/device]