Lack of leadership in accessibility isn’t just a problem for the U of O

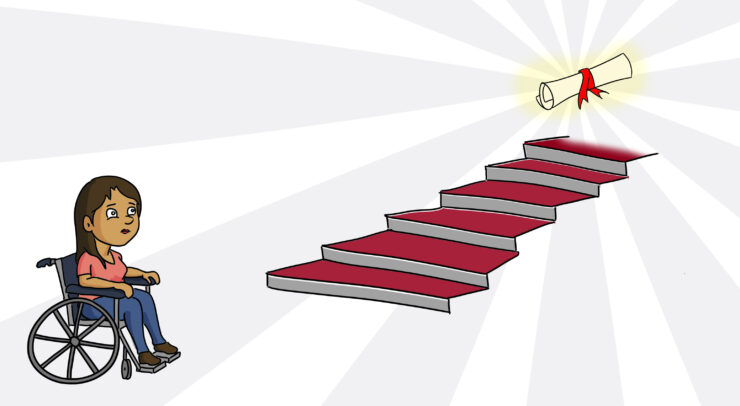

As as someone who lives without a disability, a wheelchair ramp is one of the first things that comes to mind when I think of accessibility.

But accessibility goes far beyond this, especially in a campus context, expanding to measures such as proper snow removal in the winter and ensuring that students are able to see the text on a PowerPoint in class.

On Sunday, Dec. 3, it will be International Day of Persons with Disabilities. In light of this, I decided to investigate how accessible the University of Ottawa is for persons with disabilities for this week’s issue of the Fulcrum.

Whether it’s a physical impairment or special learning needs, the conversations that I had while writing this piece brought me to the conclusion that equal access to education, both here at the U of O and at postsecondary institutions across the country, isn’t quite as easy as one would imagine.

Physical barriers to accessibility

“Borrow a wheelchair one day or pretend that you can’t walk on your two feet for one day or just an hour, and you will see how the campus is not made accessible,” says Dr. Virginie Cobigo, an associate professor in the Faculty of Social Sciences’ School of Psychology, who specializes in intellectual disabilities.

For Megan, who is in her third and final year at the Faculty of Law, common law section, structural barriers are among the biggest challenges to accessibility at the U of O. Megan had requested that her surname be omitted from this story.

“In my first year on campus, the elevator at (Fauteux Hall) was not working for about three months, which was obviously really challenging,” she says. Megan, who lives with a physical disability, notes that one of the accessible entrances to Tabaret Hall on Laurier Ave. has been closed since January of this year.

“I’m lucky that I don’t have classes in Tabaret Hall, but that’s where you get your transcripts and student enrolment and all those kinds of things, and that’s been really, really challenging over the last year.”

Alexander Latus, communications director for campus facilities at the U of O notes that for students and staff facing this same issue, there is another accessible entrance on Waller St.

Dr. Cobigo believes these barriers to accessibility boil down to a lack of leadership among the university administration. She cites challenges such as a lack of accessible doors, round doorknobs, and hallways that are not wide enough for wheelchairs in some buildings, such as Vanier Hall where her office is located.

“To be frank, I don’t think that the University of Ottawa is doing much that is good in terms of accessibility. Of course, the new buildings are more accessible than the older buildings, but it is the law. So it’s not a leadership from the University of Ottawa, it’s just that the university has to make the buildings accessible according to some minimal standards and requirements, because of the Accessibility Act.”

These older buildings, and the fact that they often fail to be modernized, pose one of the largest challenges to students and staff with mobility issues.

Leila Moumouni-Tchouassi, vice-president equity for the Student Federation of the University of Ottawa (SFUO), shares these sentiments, saying that “the buildings are very old and the university has yet to put investments after all of these years into making sure that the buildings are more accessible.”

“So often it’s the fact that a lot of buildings don’t have buttons to be able to open the doors … there aren’t ramps, there aren’t elevators, a lot of the classrooms themselves when it comes to seating aren’t accessible,” she continues.

But Charles Azar, a subject matter expert in architecture for campus facilities, explains that such problems are historic, as older buildings were not designed with accessibility in mind. According to Azar, campus facilities is trying to match or exceed current accessibility regulations using their existing budget.

“It’s also worth mentioning that the definition of an accessible building is a moving target,” he notes. “As codes and regulations continue to evolve, it becomes increasingly difficult and costly to update old or existing buildings to the current standard.”

“It also extends to more than just accessible entrances and spaces, but to all related pathways, washrooms and even signage as well. We always try to find creative and budget-conscious ways to accommodate those with disabilities, but updated, older spaces can rarely match new ones and identifying alternative accessible spaces is often the simpler or only feasible way to address accommodation requests in the short-term.”

Policies and attitudes towards accessibility

On another front, Moumouni-Tchouassi believes that leadership at the administrative level is lacking when it comes to university policies, the main issue being that they don’t accurately reflect the diverse experiences of students on campus.

“I think a long time ago (the U of O) started talking about an accessibility policy, and they still have yet to produce … and finish it and make sure that students are being able to access it,” says Moumouni-Tchouassi.

“It’s up to the university to make sure that one, in policy, it forces itself and its stakeholders to properly accommodate students, but then also making sure that when it is building all of these buildings, and when it is putting all of this money into improving this campus, that that includes making sure that it’s more accessible.”

But besides leadership at the administrative and policy-making level, Dr. Cobigo believes that negative attitudes towards disability hinder accessibility at the U of O—this is especially true for students with developmental or learning disabilities.

“I still hear some of my colleagues saying that if we use some universal design for education, the level and the quality of the education will be lowered, which is not true,” she says. “Making things accessible is not making things easier, it’s providing different formats so that the information—the content of the course—will be accessible to most students.”

Some examples of this include students submitting an audio recording for an assignment as opposed to a written paper, professors complying with standard font sizes and colours on PowerPoints so that everyone in the room can read the slides, and ensuring that all students can see the professor’s lips during the lecture, for those who may have a hearing impairment.

Dr. Cobigo notes that it can be a challenge for professors to be conscious of the complex and diverse nature of accessibility, specifically for larger class sizes, and so there needs to be training and resources available to them to ensure that they meet accessibility standards.

She suggests that this can come through having a committee chair in accessible learning, and partnerships with disability specialists. Cobigo, who is the director of the Centre for Research on Educational and Community Services at the U of O, believes that by increased partnership with the Teaching and Learning Support Service, the centre can help disseminate resources and facilitate training workshops for professors to better meet the needs of their students.

How is the university tackling accessibility issues?

So, with these issues in mind, how is the U of O currently accommodating its students and staff with disabilities?

According to Megan, Protection Services has been helpful in making campus physically more accessible for her. One of the challenges she faces is that in the winter over the past two years, snow has not been cleared quickly enough, making her walk from the parking lot to Fauteux Hall cumbersome. After speaking with Protection, they gave Megan the option of either designating a parking spot to her that would always be cleared of snow, or having her pay extra for a spot in the indoor parking garage.

“I was sort of pleasantly surprised that they were amenable to that,” she says.

At the student federation level, the Centre for Students with Disabilities (CSD) facilitates programs and activities based on the requests and needs they receive from students. According to Moumouni-Tchouassi, this means being receptive and open to students, and tailoring accommodations and services to fit their diverse needs.

“The thing about accessibility, especially when it comes to disability justice, is that there’s no one way to put it out for all people, because that in itself would be inaccessible,” she says.

In addition, Moumouni-Tchouassi says that the SFUO brings what they find from their conversations with students through services such as the CSD to the university administration.

The U of O’s Human Rights Office (HRO) also plays a major role in accessibility on our campus, through programming, training, and policy-based work.

Marie-Claude Gagnon, an accessibility policy officer for the HRO, says that the CSD has helped the office identify accessibility barriers, as well as “retrieve documentation they have worked on during an accessibility awareness week (to) share with facilities.”

Further, “the (HRO’s) … volunteers are stationed across campus to provide in-person accessibility assistance to students and staff, and help ensure easier access to resources and information available on campus. They are also responsible for identifying accessibility barriers and reporting them to the Human Rights Office,” says Gagnon.

The volunteers “wear black and white Accessibility Squad vests, which make it easy for individuals requiring assistance to identify them.”

The HRO is also involved in relaying the accommodation requests it receives to campus facilities, which is responsible for areas such as construction and the campus master plan.

Mike Sparling, manager of facility conditioning and scheduling for campus facilities notes that they have just completed a campus-wide accessibility audit from 2014-17 that included stakeholders such as the Student Academic Success Service (SASS), the HRO, and the SFUO.

“The process took three years to complete and will soon provide a “gap analysis” of our existing conditions vs. the current code requirements (that you’d see in a new building), identifying which spaces are deemed accessible or not by today’s standards,” says Sparling.

“These audits will also form the basis for a prioritized action plan to reduce barriers on campus, including providing accessible paths within buildings and barrier-free washrooms, classrooms, and public spaces.”

Student success in the classroom and beyond

Despite the numerous challenges, Megan highlighted positive experiences with SASS, a campus service providing academic accommodations to students with disabilities and specific learning needs.

SASS’ academic accommodations follow a request-based model, receiving students’ concerns with accompanying documentation from a doctor, psychologist, or other medical professional, and “from there (looking) at what courses they’re taking, what faculty they’re registered in, and (setting) up appropriate accommodations,” says Sylvie Tremblay, director of SASS.

Examples of accommodations that SASS offers include extra time on exams, smart pens that record lectures, laptops with specialized software, and ergonomic chairs and desks. SASS also works with the Office of the Registrar and campus facilities to properly accommodate students in their classrooms, such as by ensuring that a student with a disability does not have class in an inaccessible building.

But Vincent Beaulieu, academic accommodations manager for SASS, says that all this can be a challenge particularly at the beginning of the semester as students rearrange their schedules.

“Things change. Students will drop courses, register to new courses, so the beginning of each semester there’s a lot of logistics involved, moving a classroom multiple times in some cases, and then as soon as you move one classroom you have to move the other classroom, and sometimes just swapping them is not possible, it’s a lot of logistics,” he says.

And while both Tremblay and Beaulieu believe that SASS does its best to accommodate students, they recognize that they have to do so within their means. According to SASS’ 2016-17 annual report, roughly two-thirds of funding for SASS comes from the U of O itself, and only one-third from the provincial government.

“One of the challenges we’re having provincially is that that funding hasn’t gone up. In fact it’s gone down in the past 10 years, especially (with) the increase in student enrolment, increase in need as well. All campuses in Ontario are seeing much, much more demand for their services. So if you take inflation into account, if you take the growth of our services into account and all these other factors, the funding has decreased substantially, really, over the years,” Beaulieu says.

This overall lack of provincial funding means that it’s not just the U of O that is experiencing a strain on their budget for academic accommodations—it’s a province-wide crisis.

As U of O president Jacques Frémont recently shared with the Fulcrum, decreasing government grants mean that “the only place (the university) can get funding is through tuition.” So with the university itself providing roughly 65 per cent of funding for academic accommodations, this money is largely coming from students. But, as Beaulieu shares, the need for such accommodations is ever-growing.

Moving forward

“We have a bit of a dream around universal design, this idea that if learning outcomes and curriculums were more universal in their nature we wouldn’t need as many accommodations in the first place,” Beaulieu says.

Of course, this universal design, and any efforts made to make our campus and campuses across the country more accessible in the near future need to prioritize the voices and experiences of those students and staff with disabilities.

As Megan shares, “a lot of times, those who don’t have disabilities are the ones who are saying whether or not something’s accessible, but that doesn’t really help when it’s not your experience, it’s not your lived experience.”

And while stronger leadership at the administrative level is key to building a more accessible learning and working environment, this push for change starts with students. Moumouni-Tchouassi believes that “it’s important that students come together to fight—even if we don’t necessarily identify with those things.”

“It’s important to make sure that we all just generally can access education in a more equitable way, and making sure that we’re all taken care of under the same system, because we’re going to be here for anywhere from three years to it feels like a hundred, so we might as well make sure that we’re all taken care of.”

For students and staff looking to provide feedback and suggestions on accessibility at the U of O, please visit the Human Rights Office’s Accessibility Hub.