Students are directly affected by conditions facing part-time professors—and here’s why

When news broke that the Association of Part-Time Professors of the University of Ottawa (APTPUO) voted for a strike mandate, and would be in a legal position to strike if no agreement was reached by Oct. 30, much of the same messages were littered across social media feeds.

It was either “please let there be a strike so I can hand in my assignments late,” or “why are these profs striking? I just want to finish my semester.” While I recognize both of these points are important to students, they largely miss the greater issues at play.

In the 2014 fall semester, the Fulcrum wrote about the conditions facing part-time professors after they reached their last collective agreement. Although it’s been three years since that report, upon looking into the reasons behind the latest strike mandate it appears that not a lot has changed for this section of the university’s teaching staff.

But in light of the near-strike this past week, the Fulcrum believes it’s imperative to look at the ways in which the conditions facing part-time profs directly impact students—during the learning experience and beyond.

Why threaten a strike?

Given the reactions leading up to the strike, to many it may not seem like a student issue. But given that part-time professors make up 50 per cent of the U of O’s teaching staff, this could not be further from the truth.

According to Shawn Philip Hunsdale, the communications director of the APTPUO, part-time professors’ employment has always been precarious, but there has been an evolution in how their roles are used at the university.

“What part-time professors were, used to significantly be people who are recognized for their expertise in a given area, and would come in and teach a course,” says Hunsdale.

“Because of the direction that post-secondary has gone, many people are now being trained at the masters and at the doctoral level. And there is an academic streaming for this, but it means that there’s been an explosion of work for part-time professors because the university has been able to pay them significantly less.”

However, part-time professors are not just paid less than full-time professors. Hunsdale says that in fact, many part-time professors travel to teach elsewhere in the area, and they are paid 15 to 20 per cent more at other regional institutions like the University of Quebec and Queen’s University.

Jules Carrière, associate vice-president of faculty affairs at the U of O, said in response to Hunsdale’s statement that “any comparison in terms of salary scale must take into account local market which also includes Carleton.”

According to Marc Prud’Homme, a part-time professor in the Faculty of Social Sciences’ Department of Economics, in his case Carleton does pay less per three-credit course than the U of O. For comparison, he makes $6,745 for a three-credit course at Carleton, whereas at the U of O he makes $7,805 per course.

But the reasons for the strike mandate were not simply monetary—Hunsdale says that another major factor that continues to be an issue is job security.

“The university wants to make it very easy to remove part-time profs if they don’t like them or they want to replace them with friends,” Hunsdale says.

“Or they’re looking to … let’s say recruit a professor from another university, and that person says ‘oh well my wife or husband is interested in teaching, is there a spot? I would come if I could, you know, bring my spouse along.’ So the university wants to be able to take away unionized work positions and bring in spousal hires to replace these workers.”

However, when asked for comment on this allegation, Carrière said that any proposal from the university would have had no impact on the APTPUO’s membership and called this statement an inaccuracy.

Another issue that part-time profs face is the continued expectation of unpaid work on the job—a plight that many students at the U of O can surely relate to.

“A number of part-time professors are being asked to develop their entire curriculum before an offer of employment contract, that work not being remunerated,” says Hunsdale.

“A lot of the work that part-time professors do is voluntary, so it’s things like signing letters of reference, and making particular time with students to guide them through their studies within their department. This is not part of their employment contract, but when professors care they will do this anyway.”

No service

Prud’Homme has been a part-time professor in the Department of Economics for 30 years, and in that time he’s noticed a major gap in support services for part-time professors. One example among many he provided was training on new systems that professors use to provide students with learning materials.

“When we switched over to the new platform, away from Blackboard to Brightspace, most of the training was offered during the weekdays, during normal business hours,” Prud’Homme recalls. “They tried to accommodate the part-time professors, to be fair, and for the first time ever they offered the training on a Saturday. But we don’t get compensated for showing up to do training on a Saturday.”

He also noted that although the university offers a 24-hour hotline for assistance, the lack of face-to-face support for part-time professors can be problematic.

“When I needed to have some face-to-face support, I had to physically, and I have a full-time job, go to the university, and not even during lunch because they’re closed during lunch, to get that face-to-face support for that Brightspace platform or even Blackboard before that.”

Prud’Homme has a full-time job in addition to his part-time teaching, which he says makes it extremely difficult to access the same services as full-time faculty as these services tend to only be open during business hours.

Grading Scantron sheets, for example, can be difficult if you aren’t on campus full-time. “You have to arrange somehow to physically go to the university during your work hours to get those graded,” he notes.

“If you happen to have a class large enough for you to have a teaching assistant, that helps. But that’s not always the case. So you have to do it yourself, but it’s not practical to be able to do that during normal working hours. I’m not on campus.”

How does this affect student life?

Both Hunsdale and Prud’Homme agree that the issues they face while doing their job are directly related to the quality of the learning experience at the U of O.

“Whatever extra time I have to put in trying to work around all of these constraints I mentioned to you, is time away from the time I could spend with the students or preparing my classes more for instance. And so it must have an impact,” Prud’Homme said.

To illustrate how these shortcomings can affect students, Prud’Homme recalled a time when his exams were not delivered to his office and were behind locked doors in his department secretariat office by the time he arrived on campus.

“If I’d been a full-time prof I would’ve just walked into the secretary’s office and said ‘where are my exams?’ and away I go, but I didn’t have access to that,” he said.

“Because I’d been there for 30 years I knew I could phone security, and they could open the office … I was able to find them, so luckily enough.” However, this type of close call could easily end differently for other part-time professors who don’t have long-term experience at the U of O as Prud’Homme does.

Not to mention that students do benefit from professors having a good understanding of the virtual campus. As Prud’Homme mentioned, if training for these new platforms is not accessible to part-time profs due to timing or lack of compensation, students will be the ones to bear the consequences.

Prud’Homme’s difficulties with getting the Scantrons graded during his part-time hours also could mean delays in receiving grades for students who take exams under part-timers.

In addition to the logistical difficulties Prud’Homme faces, Hunsdale says that the points discussed in the latest round of bargaining are all “things that directly impact the learning conditions of students.”

“So this is things like the professor-to-student ratio. Making sure that we don’t have ridiculous class sizes. This is about basically recognizing the expertise of people who have been teaching for many years, and not to have that eliminated in favour of the university having let’s say the flexibility to appoint whoever they want to a course.”

How will the university address these issues?

On Oct. 30, the university and the APTPUO announced that they had reached a tentative agreement, narrowly avoiding a strike at the U of O.

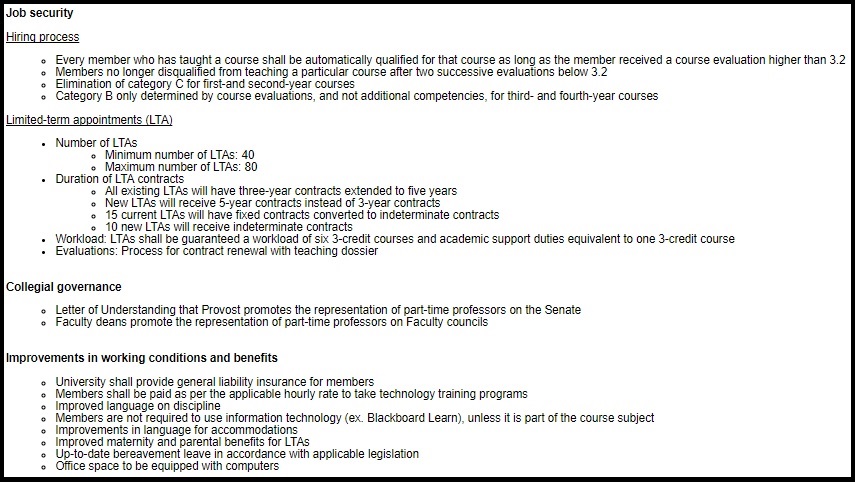

Through an email from the APTPUO, the Fulcrum was able to access the details of the collective agreement to be ratified by both parties. Although it seems some issues discussed here have been addressed, it remains to be seen how others will be handled.

On job security, the new tentative agreement features several notable changes. First, the email says that “Every member who has taught a course shall be automatically qualified for that course as long as the member received a course evaluation higher than 3.2.” In addition to this, “All existing LTAs (Limited Term Appointments) will have three-year contracts extended to five years,” and “New LTAs will receive 5-year contracts instead of 3-year contracts.”

For the monetary side, part-time professors will receive a pay increase per course of 1.8 per cent, plus a $200 lump sum bonus payment per 3-credit course taught by the member. The email notes that this lump sum payment is not included on the salary base or considered pensionable earnings.

| For a 3-credit course or equivalent taught by the member | Year 1

2016-2017 |

Year 2

2017-2018 |

| 7 947 $

(1.8%) + 200 lump sum payment per 3-credit course taught by the member* |

8 090 $

(1.8%) + $200 lump sum payment per 3-credit course taught by the member* |

Table: Courtesy of the APTPUO.

Other improvements in working conditions to be noted include general liability insurance to be provided to all APTPUO members by the university, payment by the hour for technology training programs, improved maternity and parental benefits for LTAs, “up-to-date bereavement leave,” and computer equipment in every office.

Although these details seems to be improvements on many of Hunsdale’s comments, they leave the logistical barriers to services experienced by part-time profs like Prud’Homme out of the picture.

Because this is only the tentative agreement, it is important to note that these details will not become official until ratified by the APTPUO at their next annual general meeting on Nov. 24.

Full tentative agreement information. Image: Courtesy of the APTPUO.

Fighting back against a larger trend

Even though this conflict has been mostly mitigated for now, Hunsdale says it’s important to note that these ongoing talks represent more than just the conditions facing part-time professors.

“This is about a trend which is going to be extremely significant for people of our generation, which is that of employment precarity and the rise of part-time and precarious work,” he said.

“This is simply one front where we see an employer making use of what they’re hoping to be more disposable.”

While as a student it may be easy to stay removed from the part-time prof negotiations, it’s important to remember that—if you aren’t already affected by it—precarious work conditions will be a reality that all of us will have to face.

Finance Minister Bill Morneau expressed the same prediction in 2016, saying that young Canadians should get used to short-term work and high employee turnover in their careers, and that Canada’s government must get prepared for this situation.

This is just one reason why students should pay close attention to the demands by part-time profs. Although the needs of these staff members are important to our quality of education now, their experience may be something students of today will have to face as they move into their careers.

And at the end of the day, that just might be slightly more important than getting that week off to finish assignments.