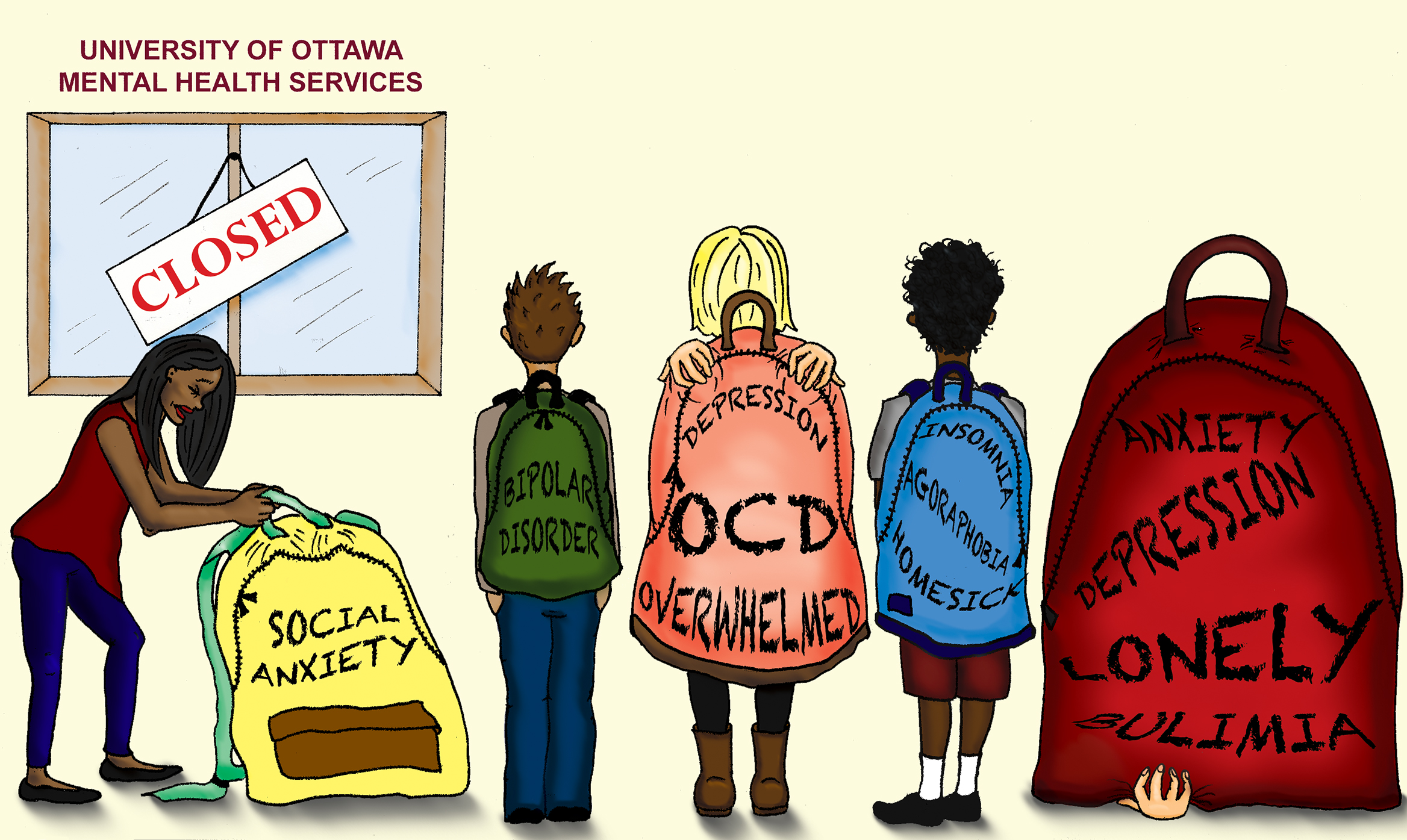

Is the U of O prepared to meet the mental health needs of its students?

The first time I entered the counselling office of the Student Academic Success Service (SASS), I felt a mix of anticipation, fear, and anxiety. After dealing with mental health issues on and off for years, and the increased anxiety I had felt during my second year at the University of Ottawa, I decided, with the support of a friend, to finally reach out for help.

The decision to seek out these mental health resources can be a difficult one—however, it is one that many students make during their time at university. Considering the fact that one in five Canadians will experience mental illness in their lifetime, and that suicide is the second-leading cause of death among 15–24 year olds in Canada, this is far from an isolated or insignificant issue.

Yet, despite the fact that mental health issues are on the rise amongst Canadian post-secondary students, the resources are not always matching up with the increased demand. With more people reaching out for help than ever, are Canadian universities prepared to meet the needs of their students?

Take a walk in a student’s shoes

The first time I made an appointment with SASS, I had a relatively short wait time. My triage appointment—where I met with a counsellor to answer a myriad of questions related to mental health—was within a week of when I first visited the office to book it.

After that, I was referred to another free counselling service on campus that dealt with more long-term issues, as SASS currently only offers short-term services, and waited for approximately one month to start my weekly sessions.

Although my first experience was positive, I have also dealt with the negative side of the U of O’s mental health services. This included long wait times and being denied services during summer months when I wasn’t registered for courses—and I’m not the only one.

Caylie McKinlay, a fourth-year political science and communications student at the U of O, and founder of the campus mental health advocacy group Students Against Stigma (SAS), faced challenges of their own when they first attempted to access services through SASS.

“There was so much focus on the fact that I was high-functioning that I found to be incredibly demeaning to my experience,” said McKinlay.

McKinlay also notes that while the short-term services can be helpful for students dealing with school-related issues, these services are not as helpful for those with long-term mental health issues. During McKinlay’s first session with SASS, they were told that SASS “can’t deal with long-term issues” and that they would have to go somewhere else.

“Sure, stress is huge when you’re a university student—but stress is a key factor in every mental health issue, and so if something’s long-term … that’s going to follow you for a long time, and so it’s important to be able to access care on campus that’s really accessible.”

Wait times were another challenge that McKinlay confronted, both at SASS and the U of O Health Service’s (UOHS) mental health counselling, where they are currently on a waiting list.

“I think the main concern and the main kind of barrier on this campus is wait times, and I don’t see that as at all an issue of the services themselves. They just don’t have the capacity to care for the number of students we have on this campus,” said McKinlay. “Would that be changed if mental health now became a bigger priority of the university to invest in? Maybe.”

Looking to administration to administer a solution

April MacInnes, senior mental health advisor at the U of O, is aware of the challenges that students are facing when attempting to access services, and is working with her team to try and help in any way they can with their limited budget and the increasing demand.

“We’re trying different strategies to respond,” said MacInnes. “Everybody needs a slightly different service depending what their needs are.”

MacInnes and her team stress the importance of the triage model that SASS and the UOHS counselling services operate under, which ensures that students are able to see a counsellor within a shorter period of time, in order to asses their needs before starting regular sessions.

“We really want to not discourage students from coming because they think it will be six weeks (of waiting). We want to make sure that they’re getting the triage at least as soon as possible,” said MacInnes. “If you’re really upset that something happened in your life suddenly, usually we can get you in within a few business days.”

Besides the triage model, MacInnes and her team are also trying to inform students about the other services offered on campus, including peer counselling, residence counsellors through SASS that deal specifically with students living on campus, active listening from the Student Federation of the University of Ottawa’s (SFUO) Peer Help Centre, and online resources such as the SASS website.

Even with all of these services on campus, many students still struggle to combat the barriers such as wait times for professional counselling. MacInnes says that in the 2014–15 academic year, the number of students who accessed just SASS counselling was approximately 1,800. While this amount seems small for a campus with over 40,000 students, it was still enough to overwhelm the U of O’s mental health resources.

“We would love to offer more services if we could. It’s just we are sort of naturally limited by budget and the demand is increasing,” said MacInnes.

MacInnes also notes that students who need help more quickly than the U of O can offer can also call the provincial mental health helpline Good2Talk, which offers post-secondary students the ability to talk to professional counsellors 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Tackling a challenge that transcends U of O campus

As more young adults around the country are dealing with mental health issues, universities are taking different approaches to lend a helping hand with the limited resources they have at their disposal.

Greg Owens, a fifth-year neuroscience and mental health student at Carleton University and president of the school’s Student Alliance for Mental Health (SAMH), believes his school’s services are good for the most part. But he admits that they are still limited in their ability to help all students who need them.

“The services are definitely positive services, but they’re understaffed and underfunded,” said Owens. “We need exponentially more of these services to reduce the wait times, ensure everybody that needs the services can be seen, and ensure proper outreach to students who are kind of tentative about accessing the services (that) are available.”

Owens himself pays out of pocket for off-campus counselling, something that students are sometimes forced to do to when they need help faster than the university can provide. However, he also recognizes that this isn’t an option for all students, especially those who are already riddled with student debt and don’t have the money to afford private counselling.

Owens also attended the University of Toronto before transferring to Carleton, and although he found the services there more helpful in some ways, as they offer more long-term services with clinical psychologists, they do not have walk-in services—something that the U of O lacks as well.

“There were multiple times (at U of T) where I showed up to the service, was in crisis myself, could see down the hallway, could see my psychologist, but basically they turned me away and said ‘you have to go to an emergency room.’”

Although Owens has not used the walk-in service at Carleton himself, he has heard from others who use it that it is “an effective service, it is a positive thing,” despite being understaffed.

McGill University in Montreal also offers a walk-in service for students experiencing a crisis, something that can be helpful for students who are in immediate need, but don’t feel that they need to go to the emergency room.

Where do we go from here?

Although all universities have different budgets, resources, and demands from their student bodies concerning mental health, one thing is clear—something needs to change.

Instead of waiting around for the administration to improve their services on their own, many students are taking the fight for mental health services and education into their own hands by creating groups and initiatives like Carleton’s SAMH and the U of O’s SAS.

Inspired by their own experience and their passion for mental health, McKinlay and their team of students from SAS are working to help spread awareness, break the stigma surrounding mental illness, and educate students about this complex topic on campus.

Although SAS’s involvement in this field began as a week-long series of events in January 2016, it has now expanded into monthly workshops and events that will take place throughout the school year.

“(We held) a lot of events focusing on making the mental health campaign more inclusive and a little bit more controversial because something that’s always kind of bothered me about the typical mental health campaign is that they focus on depression and anxiety, and then they never really touch anything else,” said McKinlay.

McKinlay and the students involved with SAS are not only working to spread awareness on campus about mental health, but also trying to put pressure on the administration to improve the services offered on campus.

“It’s clear that this conversation is here and this conversation is so on people’s minds. People are so ready to talk about it. It’s just, like, let’s get action going now,” said McKinlay. “Awareness is cool—let’s get action now.”

Owens also says that SAMH is trying to help students learn more about mental health and the resources on campus, as well as navigate what can often be a challenging and confusing system.

He says that SAMH has three main components—support work, advocacy work, and education work. Through this structure they not only hold workshops to help educate students, but also work with the administration to help ensure students are getting the help they need.

As for the U of O administration, MacInnes and her team recognize the need for more resources on campus, but said it’s a difficult issue to tackle as demand increases and the budget doesn’t.

“I really would like the communication to be improved. I would really like people to understand the plethora of services that are available so that if they go to one door and it doesn’t work for them, that they (can) go to many other services,” said MacInnes.

One way that MacInnes and her team are working on improving communication is by launching a new website this November that will help students get a better idea of services available to them. She said they are also working with different groups and faculties on campus to ensure that the importance of a smooth transition is focused on first-year students.

Overall, it seems like the U of O administration is working with what they have, and the only way things will really get better is by an increased budget with a bigger focus on mental health issues that affect students.

For now, all students can do is keep fighting for more and better services, and try their best to get the administration’s attention.

As McKinlay puts it, “students really, really need better services, and we’re not going to be silent about it.”