Annalise Mathers sat down with everyone’s favourite ByWard Market chalk artist Francois Pelletier to see what life is like from his side of the pavement

Photos courtesy of Francois Pelletier

I’m in a rush. My cell phone tells me it’s 1:56 p.m., so I’ve only got a few minutes to spare. I bustle through the single door of Second Cup on Dalhousie Street and Laurier Avenue, the wind blowing me in.

I’ve barely got time to wonder how I will recognize him before he’s in front of me at the cash, drink in hand. It’s one of those all-knowing moments: we lock eyes and I know it must be him.

Pelletier, the infamous chalk painter in the ByWard Market, is tall — he has a good couple inches on my own six-foot frame — and he’s well shielded from the weather, wrapped in neutral, bulky winter clothes. He has short brown hair, slight stubble, and animated brown eyes that hold a mysterious gleam.

Gazing around, we agree on a spot to sit that’s apart from the inner workings of the café, opting for a quieter locale away from the din and hustle. I order a coffee and fill my cup with milk and sugar. When I turn to our chosen spot, I’ve lost him.

Did he leave?

I amble over to our agreed-upon seat and begin to unpack my things. Maybe he went to the bathroom?

As I sit down, I realize he’s chatting to the barista, the same one he was talking to before I came in. That’s the first thing I realize about this enigmatic artist. He can strike up a conversation with anyone. It comes naturally to him, and he willingly takes time out of his day to do it.

After a few more moments of idle chatter with the server, he strolls over to me and drapes himself on the chair opposite. He sheds one of his winter sweaters and we immediately strike up an amicable conversation about why I am writing this article. It quickly becomes clear that he’s done this before; he is a natural to talk to, and comes alive at the table. I sense an incredible vitality, especially as we begin discussing his work.

The perfect word to describe him is personable.

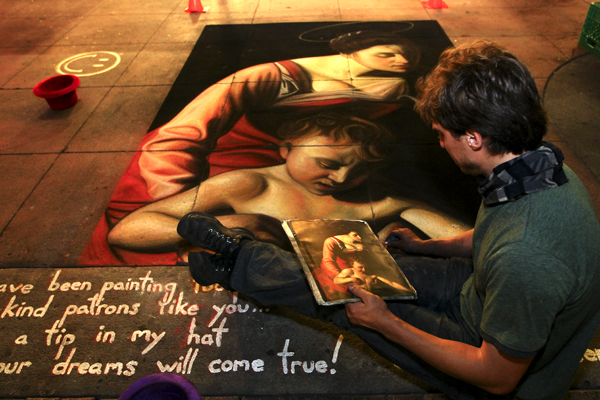

Pelletier is the first person I think of when it comes to interesting art in Ottawa: the mystery man in the market who does those incredible chalk drawings outside Sugar Mountain on the well-used pedestrian walkway on William Street. If you’ve ever walked downtown, you know exactly what I’m talking about.

That’s the thing — you know what I’m talking about, but not who. And this was my goal, to find the face behind the chalk pastel overlay of beautiful art.

Tracking him down was easy. A rapid Google search of “ByWard Market chalk artist” yielded many results. With a few more clicks, I had a name and then an email address. I fired off an email and got a prompt response within hours. He’d love to be interviewed. Over the next few days, we emailed back and forth.

He was leaving for Italy at the end of January and wouldn’t return until mid-Spring. He generously offered Skype, email, and phone interviews, but I wanted the first-hand experience of talking with him. We arranged to meet the day before he left the country.

As the conversation continues, we get caught up in the most pressing event in his life at the moment: his trip to Italy.

“I’m going to help a friend who is renovating his house into a bed and breakfast,” he says with a laugh, a throaty, generous sound.

He goes on to describe the house, set in the mountains of Italy just north of Rome, where he will be helping his friend while also drawing in the streets and “getting to know people, not just sight-seeing.”

“Every city is something else, more beautiful than the last,” he says about his trips through Paris, Italy, and Spain. “Cities built for people to walk.”

Naturally, these pedestrian-heavy cities lend themselves to his trade. France, the first place he travelled to and chalked, was where he began to notice the stark difference between the way Canadians and other nationalities regard his art.

“In France, street art is accepted as a career. It’s seen as a trade. There’s no judgment, no wonder in the people’s eyes. There’s an innate respect for what an artist is and what he does,” he says.

“Any kind of artist has a status that is respected — art is seen as a trade. Here in Canada, art is a hobby and economical factors are too important. In Canada, money overshadows what I’m truly doing.”

His current locale of choice is Melbourne, Australia, which he considers “the place to be,” where he can feel the city’s rhythm. As he speaks of it, he playfully adopts a mock Aussie accent. With seasons opposite to our own, Melbourne is also an ideal escape in favour of harsh Canadian winters where snow and ice pause his sidewalk work for half the year.

Pelletier is a cultured man. His French background comes out strongly in the first half hour of our conversation as he mutters “comment dit-on” when he tries to find the English translation. As we speak he mixes his drink, pouring small portions of water into his large Americano.

He grew up in Embrun, Ont., a small town just outside of Ottawa, but identifies himself as a downtowner, where he’s grown and lived as a young adult.

At first, he strikes me as having an odd lifestyle, one of seclusion and loneliness. But I quickly realize that it’s the exact opposite. It seems many of his relationships bloom from personal interest and admiration of the universal language of art.

“My work is gratifying. It brings together the local crackhead, an ex-girlfriend, the lawyer, and me, all on the same level,” he says. “I look up and realize these people never would have spoken together if they hadn’t seen my work. It allows a certain contact that is so rewarding to see.”

He’s honest, stoic, and unfazed by the realities of an Ottawa that many of us hardly know, the inner underlying facets of our city and its inhabitants.

What also strikes me is how well-known he is. During our interview, he pauses mid-sentence and points out one of his friends walking along outside the café. I’m impressed. For a man who is a mystery to much of the university community, he has an encompassing circle of people he knows because of his work.

Pelletier is also an alumnus of the University of Ottawa. After taking art classes at De La Salle High School, he pursued an undergraduate degree in religious studies. Throughout his time at the U of O he remained loyal to his craft as art was his main income.

Art runs in Pelletier’s family. His father was a painter, and while he never pressured Pelletier or his brother to pursue an artist’s life, both fell into the craft naturally. Pelletier’s start began when his brother took up chalking in the Market after seeing another painter when he was young. He recalls his brother coming home with a pouch of money, and thinking “it was magic.”

He quickly realized it could become a source of income, and at age 16 he completed his first piece with his brother called Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. Since then, he’s never looked back.

“My work has really snowballed,” he says.

And it’s true. Sixteen years later, at age 32, he’s still at it.

“It’s what I do. It’s normal,” he says. “The rewards are gratifying, making people happy and seeing their reactions to the piece. Not to the guy who did the piece, but just simply the piece itself.”

An hour into our chat, he stops and says he’d love a smoke break. He throws on his sweater, coat, and a thick fur hat as I bundle up, and we trudge outside to the corner of Dalhousie and Rideau Street. We talk for another 15 minutes or so before heading inside.

After resettling I broach the question many of us wonder: How much does he make? He assures me that there are the extremes, “both just as rare,” ranging from $10 to $1,000 in a day, noting that busker fests are much more profitable, as people at these events are more sensitive to busking as a living. Otherwise, springtime and Canada Day are among Pelletier’s most profitable times.

Back inside, he adopts the same casual pose as before, shifting every now and then to limber up his joints that stiffen over the winter from a summer of hard work.

He laughs and says, “I can’t give it up.” Pelletier has set no end date for his chalking days. He knows there is a limit, as the pavement takes its toll on his body, especially as the cold sets in. His only comment is that if and when he moves on, it will be to a different trade.

A typical week for Pelletier is the opposite of our own. He structures his week around the weekend, usually beginning a piece on Thursday or Friday (after several coffees to gain full cerebral consciousness, he jokes). He takes breaks around noon, when the sun is at its peak, and continues until dusk. A piece typically takes him three days to complete. Saturdays, when the Market is at its liveliest, are when his work truly begins.

His currently focuses on portraits and compositions from Botticelli, Leonardo Da Vinci, and Michelangelo.

When I ask about the negatives of his craft, he’s quick to say that there are some things he can’t avoid.

“The weather is a force on its own,” he says. “You can lay tarp down, but ultimately you hope for the best.”

It’s much the same for vandalism, something he doesn’t understand or get used to, but something he recognizes as an integral part of his work. It’s unavoidable, especially as a street artist. He can tell what went on the night before by how intact his painting is.

For his work, Pelletier uses soft pastels, not exactly the sidewalk chalk we grew up with. Throughout his career, he’s moved around the Market, but has established himself most as the guardian keeping vigil outside Sugar Mountain.

“The smoothness of the ground is perfect, as it holds the chalk, and it has just the right amount of sun exposure and traffic,” he says.

The pedestrian nature of the area lends itself to inquisitions and donations from passersby. However, the unspoken code of this work means if someone else chooses the spot, he’ll relocate. It’s first come, first serve.

“Chalk art is always a work in progress, it’s an organic thing,” he says. “There’s no A to B to C, or any point where you can say it’s finished. It’s about always making changes and adjustments.”

He notes that he used to be more detailed, but now focuses on the technical challenges and adds in his own twists and improvisations to his Renaissance recreations.

However, he’s sometimes able to keep a close eye on his work in the Market perched nearby at one of his favourite restaurants, The Grand. His other favourite, a hidden gem, is Chez Lucien.

“It’s not just an assembly line restaurant,” he says. “It’s true service where I’m really comfortable.”

His expertise has also extended to classrooms, where he’s been invited to teach some classes to children. He finds the work very rewarding and has even had some past students come up to him in the Market and thank him for being their own inspiration.

He’s quick to remind me of his humble nature though. When I ask him if he’s ever had an apprentice or student work with him, he laughs and retorts, “That would mean I’m a master.”

Pelletier’s work explores a field of art that dates back to the 1500s in Italy, where painters would draw the Madonna in public areas with chalk to give thanks. He is touted as a “modern-day Madonnari,” which is a fancy name for a street painter. The term is elegant, but very fitting for Pelletier.

He mixes this classical art vibe with some of his music interests to complement his art: classic rock, soul music, the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Barry White, or whatever fits his mood.

He’s a man of simplicity with a “you want it, come get it” mentality. He can’t even be bothered with self-promotion.

“I should kick myself and get a website, but it gives me headaches,” he says.

Simply put, he’d rather meet people out in his natural territory, the pavement, with a trusty pastel in hand.

Eventually, he has to leave the coffee shop. He has other places to be and people to see before he departs to Italy. He leaves me with an embrace and a traditional double-cheek kiss like we’re great friends parting. As he exits, he walks by the window where, moments ago, he had just sat, and peeks in at me, waving and smiling.