Members of the local academic community chime in on one of the fastest growing environmental movements in the country.

When it comes to a lot of big world issues—like war, poverty, and disease—many young students feel like they are powerless to do anything.

This is especially true when the topic turns to fossil fuels and climate change, since influential decision-making regarding these hot-button issues are made behind closed doors here and abroad.

This is probably why the fossil fuel divestment movement has been picking up steam over the past couple years and why it has been so popular among university students—it seemingly puts the power back in their hands.

For those of you who don’t know, divestment is an economics term that means the opposite of investment, whereby you actively look to shed financial ties with an institution in the form of stocks, bonds, and mutual funds.

The fossil fuel divestment movement aims to apply these principles for environmental purposes, persuading various institutions to stop investing in oil, gas, and coal, commodities that negatively contribute to our society’s global carbon footprint.

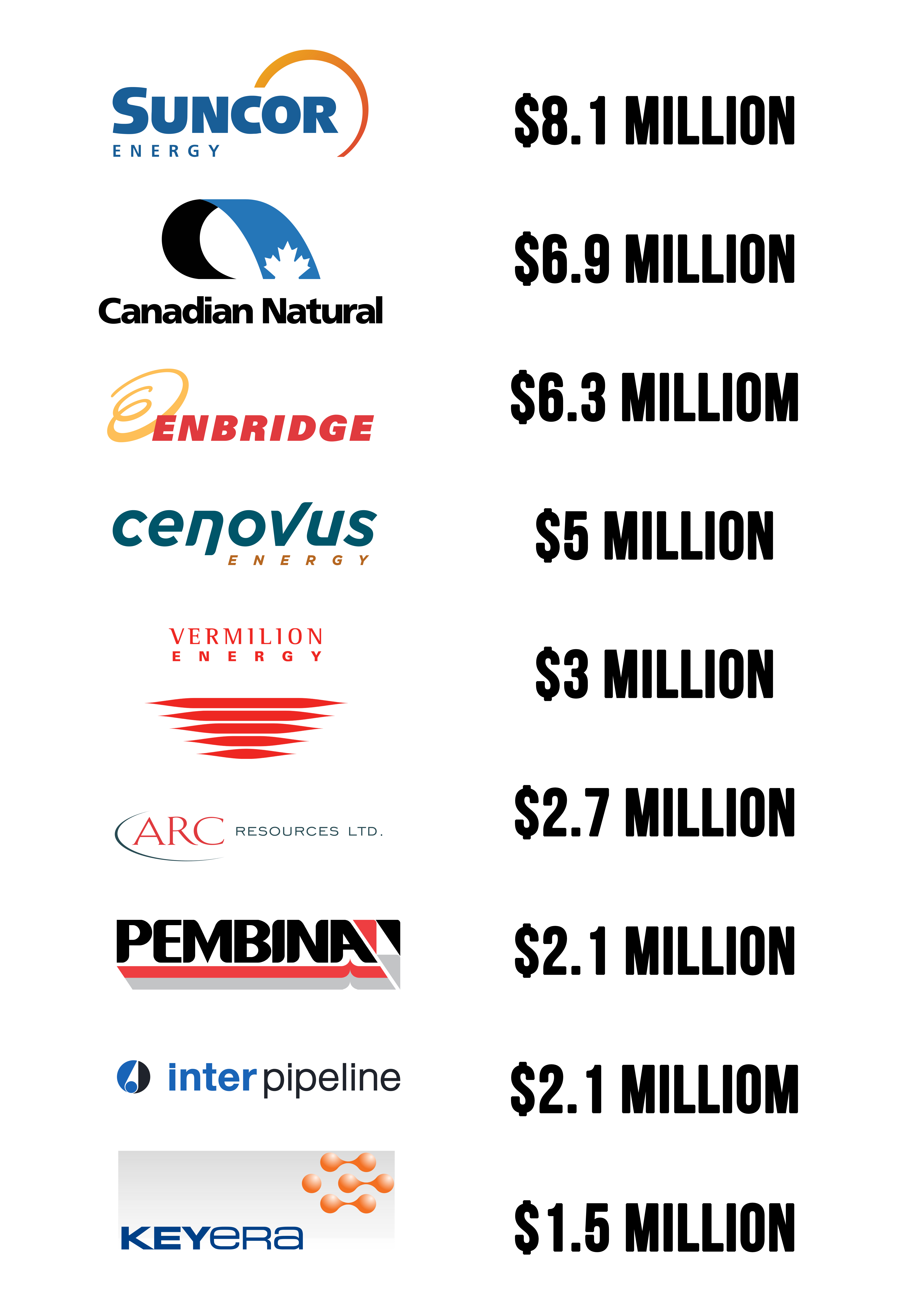

This movement is grassroots right down to its bone marrow, having started in Canada in 2012 by a group of students from McGill. Since then, the campaign has spread to more than 30 university campuses across the country. This includes the University of Ottawa, where local activists like Fossil Free uOttawa are hoping to convince the administration to drop the estimated $55 million that they have invested in companies like Suncor ($8.1 million), Enbridge Gas (around $6 million), and Cenovus Energy ($5 million).

The U of O’s domestic fossil fuel investments above $1 million

Source: the U of O’s 2014 Canadian equity holdings. Image: Kim Wiens

However, like most social phenomena, the fossil fuel divestment movement is not without its detractors.

Some say that it’s an impractical way of fighting climate change in an economic sense, while others characterize the movement as a bunch of whiney Millennials making noise over an issue that they don’t fully understand.

So is this divestment movement an effective way of bringing about meaningful change, or is it simply another shallow, moralistic crusade that is all flash and no substance?

Moral conundrum

One of the biggest ideological pillars holding up this movement is a moral argument, with many believing that intellectual institutions like the U of O should not financially support the use of a commodity that is endangering the well-being of its students and society at large.

This belief is shared by over 100 present and retired U of O professors, all of whom put their names to an open letter addressed to president Allan Rock and the Board of Governors (BOG), urging them to “divest the (U of O) endowment fund and the employee pension plan from fossil fuel companies.”

Students from Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts rally to protest fossil fuel investments. CC: James Ennis.

“The time is well overdue for us to make this transition away from a fossil fuel economy,” said Adam Brown, a U of O biology professor who is amongst the local academics who signed this open letter.

“Our window of opportunity is closing. So there’s no longer an argument to be made about ‘Oh, let’s just take our time and let’s do things slowly without big jumps.’ No. The time is now.”

Brown is also compelled to participate in this campaign as a matter of professional integrity.

“As a biology professor, and particularly one with an expertise in ecology and environmental science, it is incumbent upon me to share that information with other members of the university community and the public at large.”

While this moral angle has been critiqued by some, it is not without historical precedence.

After all, the same kind of university-centred divestment activism was deployed in the 1980s to combat South African Apartheid, which many believe played a fundamental role in rallying public opinion against state-sponsored racial segregation.

However, some think that this same kind of moral outrage is not applicable to the fossil fuel industry.

U of O economics professor Gilles Grenier believes that this latest divestment movement is extremely short-sighted, especially when it’s put in an international perspective.

“I’m thinking from a humanitarian point of view,” he said, referring to third world countries, where a large chunk of their population have to settle for oil or coal, since they simply don’t have the means to access green sources of energy.

“If you’re very poor and you’re offered the possibility to have electricity in your house, maybe you’ll value that more than potential environmental disasters that will happen 100 years from now.”

Grenier states that this sort of activism becomes even more of a moral quagmire when one considers Canada’s international trading partners, some of whom have environmental priorities that are far below our own.

“Suppose the Chinese ask Canada to sell oil… and we say no. What do they do? They just keep using coal, which will have a worse effect on greenhouse gases than if they use oil.”

Taking them down from the inside

The short-sighted moralizing that Grenier alludes to is present in the financial side of the debate as well.

According to Dr. Tessa Hebb—a responsible investment expert from Carleton’s Centre for Community Innovation—divestment is largely ineffective in terms of enacting concrete fiscal change, and that institutions like the U of O would be in a better position to help reshape the energy sector by holding onto their shares.

“What’s more effective, in my view, is for the shareholder or the investor to maintain their position in the company and use their influence as shareholders in order to change the standards by which the company operates.”

Hebb goes onto say that by divesting one’s investments in fossil fuels, these institutions would be giving away all their influence and power in the free market, and will be left with no bargaining chips to speak of. Plus, they also run the risk of putting their shares in the hands of morally dubious institutions.

“When somebody sells their holdings, somebody else buys and usually the person that buys, or the institution, doesn’t care. It doesn’t have any interest in the (environmental) issues at hand and we’ve seen this quite a number of times.”

However, biology professor Jessica Forrest—another signatory of the open letter to Rock and the BOG—counters this strategy, saying that it is “incredibly naïve.”

“These are fossil fuel companies. It’s not like you can pressure them into extracting our fossil fuels in a nicer way. I mean their business model is based on the extraction and consumption of fossil fuels, so I don’t see, given the stakes and given their business model, a way that leverage from the inside can work.”

Students from Australia National University promoting divestment. In Oct. 2014, their administration decided to divest from seven fossil fuel companies. CC: Cafe cafes Cafe cafes.

Brown also dismisses this taking-them-down-from-the-inside narrative, saying that these investments won’t even be worth much in the near future since, in his eyes, “the fossil fuel industry is a dying trade.”

This idea is easier to believe now more than ever, especially in a world where the price of oil has slid to around $32 a barrel and where some of the country’s largest pension plans (including the Canadian Pension Plan and the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System) have reportedly lost billions through their fossil fuel investments.

“It makes poor financial sense to continue to invest in a dying industry,” Brown continues. “This is economics 101. If there’s no future in the industry we are throwing our money out the window.”

Possible solutions

The big elephant in the room whenever the subject of divestment comes up is: how do we keep a fossil fuel-free energy sector going when the industry has been dominated by fossil fuels since the industrial revolution?

In the eyes of many, renewable energy sources (think wind, solar, hydro, etc.) are at a point in their development where they are ready to take up the burden that oil, gas, and coal have carried for so long, if only they were given a chance.

“What we lack is the political will. What we lack is leadership from companies,” said Misha Voloaca, a PhD student and member of Fossil Free uOttawa, when asked why these clean energy sources have been taking forever to get off the ground.

“One of the reasons why it’s been so slow is that fossil fuel interests have played a significant role in disrupting the public conversation around climate change, especially in the United States and other places where they are pumping hundreds of millions of dollars into campaigns to prevent laws and policies from being implemented.”

According to Clean Energy Canada, our country invested $11 billion in renewable energy in 2014 (an increase of 88 per cent). CC: Chris Lim.

While Hebb also believes in the potential of renewable energy sources, she states that these seismic shifts in the industry might be a couple years off, and recommends some more practical steps that can be taken in the interim.

“I think that the investors should measure the carbon foot print of their investment portfolio and seek to reduce that carbon footprint over time.”

“This was actually a step that the University of Ottawa took in the late fall of 2015,” she said, referring to the school’s decision to sign the Montreal Carbon Pledge, thereby agreeing to publicly disclose the carbon footprint of their investment portfolio.

Being more of a skeptic on the subject of divestment, Grenier is content with sticking to the energy sources that have worked in the past, and states that we should continue to invest in the technology we have now and use them in a more environmentally friendly way.

“I think we will still need fossil fuels for a long time, so we should try to make the best of it.”

Divestment at the U of O

Of course, the fossil fuel divestment movement extends way beyond Canadian university campuses.

Thanks in large in part to endorsements from religious institutions like the World Council of Churches, philanthropic juggernauts like the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and international groups like the United Nations, more than $50 billion in fossil fuel investments have already been divested globally (with some even claiming that the number goes as high as $3.4 trillion).

Protesters mobilize in Berlin on Nov. 2015 to spread the message of divestment. CC: mw238.

However, Canadian university administrations are still hesitant to adopt these measures, as not one of them have taken the plunge in an official capacity.

“University administrations are, by their nature, conservative,” said Forrest. “And, of course, they have a responsibility to safeguard their investments and make sure that their pension will be there down the line. So they can’t rush into things.”

With that being said, the U of O has been flirting with the idea of divestment for the past couple months. Not only has the topic been brought at the BOG meetings in January and February, but a series of on-campus, divestment-related panels have been scheduled for late March.

Additionally, the administration has also commissioned several fossil fuel reports to help them decided whether or not divestment is the right way to go, one of which was submitted by Hebb herself.

But despite these recent steps, Brown is not holding his breath.

“Talk is cheap and action is where we will see results,” he said. “Until we have a complete disassociation from investment in fossil fuels we are still a very big part of the problem.”

And while the debate still rages on about the validity of this movement as a means of bringing about meaningful change, Forrest testifies to the idea that this brand of activism is still a great way to spread awareness of the environmental issues plaguing our planet.

“If we’re going to be at the forefront I think you should look at the university’s campaign, ‘defy the conventional.’ I mean what could be more conventional than fossil fuel consumption.”