The strikes at the University of Toronto and York University have brought widespread attention to an issue that has been bubbling just beneath the surface of Canada’s post-secondary institutions for quite some time.

On Monday, Mar. 9, York teaching assistants voted not to accept the university’s proposed deal, having been on strike since Mar. 3. Meanwhile the TAs at U of T have been on strike since Feb. 27.

But this isn’t a Toronto problem. It’s something more widespread and systematic, and it threatens the quality of both our education and the students who come after us.

In September, the CBC reported that across Canada, undergraduate students are more likely to be taught by contract faculty than by anyone with tenure. At the University of Ottawa, your chance of being taught by contract faculty alone is just under 50 per cent. Add TAs to the equation, and well more than half of the university’s teaching staff are not full-time employees.

Universities are hiring fewer full-time professors, instead opting for having contract professors and TAs to do a large part of the teaching. An overabundance of qualified candidates for any academic position has created a job market where universities may feel they can afford to offer less and ask more.

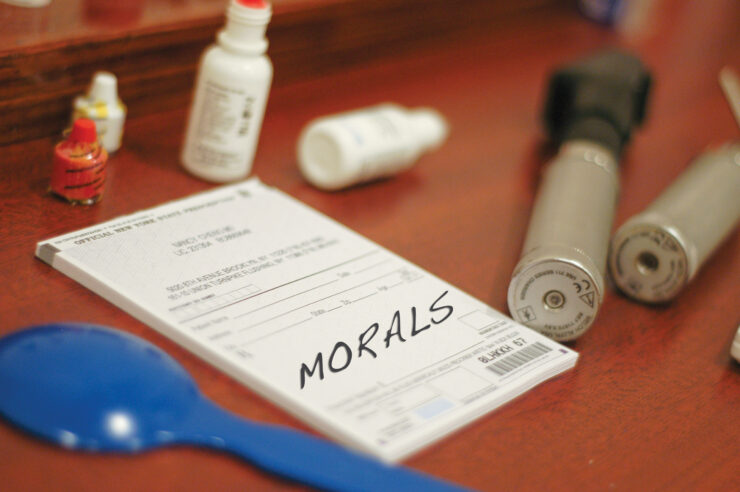

At the U of T, graduate students are striking because they are being offered a wage that sits well below the poverty line. They are making $42.05 an hour and the university has offered to raise that to $43.97. However, they are currently capped at 210 hours a year, and they can only make $8,965.06 a year. The “better” offer involves a cap of 180 and they can make $8,231.18. The “raise” works out to a pay cut of more than $700.

Further, their minimum funding package of $15,000 has outlasted several raises to the minimum wage, and throughout negotiations, the administration has been unwilling to discuss a change.

What we should know from the frequency of teacher strikes at every level is that anyone running a classroom is working hours that are not accounted for in their pay. Between answering student emails and calls and marking exams and papers, teachers spend a lot of time working for free.

This is made more difficult for TAs as they are expected to simultaneously perform well as students. They are often making up for the lack of pay with scholarships that are dependent on maintenance of marks.

Those of us doing undergraduate studies are getting some of the least experienced, most stressed out professors available, and those people aren’t even being fairly compensated.

While we may not attend these schools, we should be watching what happens there with interest. Only last year, the U of O was in negotiation with its own TAs. If either York or U of T offers something that can change the system for the better, we should be lobbying to adopt that system here.

It’s a systemic problem that cannot be solved by making small appeasements and hoping the TAs and contract professors will go away. It isn’t a problem between administration and teaching staff. It’s a problem that impacts the way we choose to define post-secondary education.

If tenured professors are busy doing research and universities are choosing to invest in that research, it’s not a bad thing. But the other function of a university is teaching its students. If the administration chooses to do so with contract faculty and TAs, then they need to offer them a way of doing so without having to live in poverty.

Reports from the Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star suggest that TAs want to get back to work and they are willing to negotiate with the administration. But first, they need to get an offer that isn’t an insult.