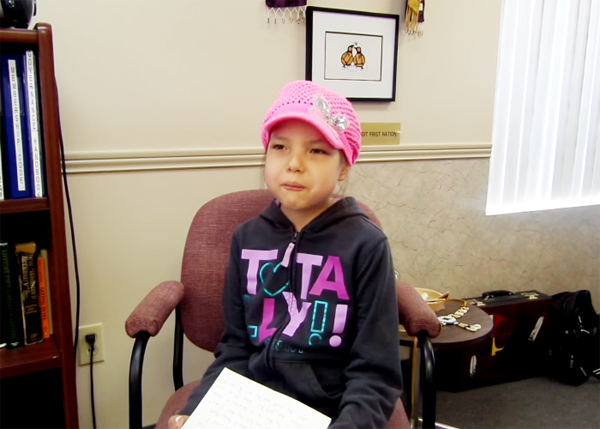

Makayla Sault case highlights need for more cultural understanding

Photo: Youtube

The death of Makayla Sault, an 11-year-old Ojibwe girl who succumbed to a rare form of leukemia back in January, is a particularly sensitive topic amongst Canadians. Since her family’s decision to refuse potentially life-saving chemotherapy treatment is protected under Canadian law, one might wonder whether children like Makayla should be forced to undergo modern medical treatment, even if such an action violates their aboriginal rights.

The answer might be clear to some. But the idea of forcing “foreign” cultural beliefs on a girl like Makayla would only lead to more distrust between natives and non-natives, which would, in turn, result in more sickness and death.

It’s no secret that racial animosity toward First Nations people is still a rampant problem in our country. Not only does it breed discriminatory attitudes, but it also leads to a profound societal divide.

On their website, The University of Ottawa’s Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine notes that “(t)he present day effects of colonization include a lack of cultural understanding between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canada and strong feelings of distrust between the two.”

This mistrust can even extend to the realm of medicine, since many native peoples in Canada continue to view modern medical science with suspicion. This is especially tragic when you consider the fact that, as a result of this mistrust, aboriginal Canadians are dying at record rates compared to non-Aboriginals.

Still, even though there was a high probability that chemotherapy could have saved the life of someone like Makayla Sault, an aggressive attitude was probably not the best solution to this problem. The image of Canadian-sanctioned authorities forcibly removing aboriginal children from their homes in their supposed “best interest” brings up dark memories of residential schools, and probably would have sown the seeds of further mistrust down the line.

Going forward, a better approach would be to encourage the recruitment of more culturally sensitive healthcare workers.

There is a need for more culturally competent doctors in Canada, especially in remote areas with a concentrated aboriginal population. The most efficient way of accomplishing this is to recruit more aboriginal doctors, since they are often best equipped to administer culturally competent and safe care to First Nations populations.

The Faculty of Medicine at the U of O has been attempting to encourage this kind of recruitment for the past decade by hosting a mini-medical program called Come Walk in our Moccasins. The program is designed to give aboriginal high school and post-secondary students a feel for medical school and to encourage them to apply for an MD program. Hopefully more programs of this nature will become the norm at Canadian universities so we can help reduce the health disparities of Canada’s native population by graduating more aboriginal doctors.

The sooner this gets underway the better. Right now another aboriginal girl in Ontario—whose name is subject to a publication ban—has, like Makayla, pulled out of chemotherapy treatment, opting instead for traditional aboriginal remedies to treat her cancer.

Even though Ontario courts have recently extended the appeal period to challenge this ruling, the government is at least discussing with her family culturally respectful ways to provide effective healthcare. If all goes well, the goverment is bound to come to a better conclusion than threatening to force chemotherapy on a child.

While Canada still has a long way to go with improving aboriginal relations, practicing more cultural sensitivity in the healthcare sector is at least a good step forward.