With rising cases of the degenerative brain disease, CTE, something needs to change

When it comes to concussions, the NFL and its players need saving—from themselves.

It’s not called America’s Game for nothing—people truly love football. But whether the love for the game stems from the unmatched athleticism and skill it puts on display, from the excitement it provokes—or even from Fantasy Football—one thing is for certain: everyone loves football’s big hits.

Of football’s many cheer-rousing collisions, one in particular, a takedown of St. Louis Rams Quarterback Case Keenum, drew a far less inspired reaction. After being violently slammed to the ground by his opponent, Keenum remained down and rolled around in a confused daze, clutching his helmet. To the disgust of fans and analysts alike, he was kept in the game. It was later revealed that Keenum had suffered a concussion on that play.

This highly scrutinized play calls attention to the issue of concussions in the NFL.

Old-timers once cavalierly called it “getting your bell rung”, but concussions have since evolved into a very serious problem in the NFL. The issue was recently brought even further into the spotlight, with the discovery that Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) is rampant among ex-NFL players.

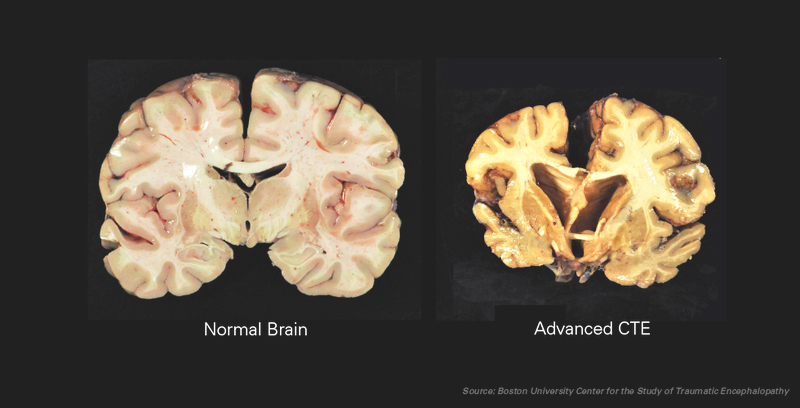

CTE is a degenerative neurological disease associated with Tau protein build up and tissue loss in the brain. The disease is caused by frequently sustained brain traumas, including concussions.

The symptoms can be crippling, and include memory loss, aggression, personality disorders, and depression—the symptoms indicate a progressive decline of overall brain function.

“There is a compelling need to better understand the underlying mechanisms of traumatic brain injury and to develop neuro-protective and neuro-regenerative strategies,” says Mahmud Bani, a professor in the University of Ottawa’s Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine.

Unfortunately, the presence of CTE can only be detected postmortem. But with many ex-NFL players growing older and dying, more and more studies have been conducted on their brains, revealing cases of CTE at an alarming rate. In studies performed by Boston University Medical School and the Sports Legacy Institute, 96 per cent of those brains examined in deceased NFL players showed evidence of CTE.

Recently, cases of CTE have manifested themselves in more troubling ways.

In 2012, retired NFL Hall of Fame player Junior Seau shockingly committed suicide. Brain pathology reports from his autopsy confirmed that Seau suffered from CTE. Later that same year, 25 year-old Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Javon Belcher shot and killed his girlfriend and then himself. Autopsies later revealed that he too had the disease.

In spite of these disconcerting reports, concussions remain rampant in the NFL. In fact, there is still an average of 167 reported concussions sustained each season, according to NFL Health and Safety.

However, many concussions go unreported by the players who suffer them. Thanks to the macho culture entrenched in football, oftentimes an injury—such as a concussion—that won’t directly hinder the player’s ability on the field, is concealed or even ignored.

Unlike a knee injury, the effects of a concussion are often insidious and far worse in the long run.

While the NFL has taken steps to make right by the past and compensate those for whom it is already too late—the league settled a massive civil lawsuit which paid $1-billion to thousands of ex-players suffering from neurological disorders—they have yet to solve the current problem, and many of today’s players seemed destined for a similar payout.

The league has put forth several new initiatives in an effort to slow down the current concussion epidemic. These include increased penalties for headshots, concussion spotters watching every game, and funding for youth football head trauma awareness programs. It is yet to be seen whether these measures will be effective.

The concussion crisis has not only shaken the NFL, but has affected even the lowest rungs of the sport—youth football, and in turn has put the future of pro football in jeopardy. Many wary parents are no longer letting their children play football, and as a result, Pop Warner, the largest youth football program in the U.S., has seen a 10 per cent decline in participation between 2010 and 2012 alone.

The game of football and, more importantly, its players are in danger. But what can be done to save them both from a dreary future?

Spreading awareness and teaching safe fundamentals can only do so much—too many young men are still suffering concussions in the NFL. And with the medical community in complete unanimity regarding the life-threatening nature of frequent concussions, more significant measures must be taken.

Should the league implement more penalties, fines, and rule-changes be implemented to ensure greater chances of player safety? Recent efforts in that direction have yielded minimal results. Many purists warn that taking those efforts further could turn the NFL into a glorified game of touch football.

While the disturbing medical reports continue to pour in, banning the game remains unthinkable. However, the NFL needs to show improvements, and fast, before the ominous ultimatum is presented. Let America’s most beloved game wither, or continue to let its players die.