UOTTAWA UNDERWATER ROBOTICS CLUB TALKS UPCOMING COMPETITION AND DESIGN

What is a robot, really? No, seriously. I asked google this morning, and I got some mixed results.

Sources claim that at its core, a robot is a machine controlled by multiple programs and algorithms working together that allow it to carry out complex tasks. Others swear it’s a series of electrical components, like resistors and capacitors. But is a robot just the sum of its parts? Perhaps not, but rather a magnificent and fascinating nuanced interaction between both its code and components.

Robots are also famous for reasons beyond their engineering complexity, mainly because of a not-so-nice term, “killer robots,” that is largely associated with the idea that robots will eventually rise up against us and kill everyone we love. This idea was partly inspired by movies like The Terminator and I, Robot, but why must we villainize robots? They can’t be all that scary (except you, Boston Dynamics dog, you are insane).

Fears aside, the Fulcrum spoke with the University of Ottawa’s underwater robotics team to discuss the ins and outs of Kelpie Robotics and what’s next for them.

Who is Kelpie Robotics?

The team is broken down into four sub-teams including, electrical, mechanical, software, and business, however, leading the brigade is team captain (or chief executive officer) Juan Hiedra Primera, a fourth-year electrical engineering and computing technology student. Within the electrical sub-unit is Mohamad Ali Jarkas, a fourth-year electrical engineering student who is responsible for electrical systems design. Last but not least is Kaitlyn Dompaul, who is in their final year of computer engineering at the U of O and their first year at Kelpie Robotics.

The name Kelpie, explained by Jarkas, is based on a water-shapeshifting spirit in Scottish folklore. It has also been described as a black horse-like creature, able to adopt human form. Within said form, kelpie retains its hooves, leading to its association with the Christian idea of Satan — not too far off from the killer-robot aesthetic.

Internal Structure

Much like Formula uOttawa, a lot of engineering involves breaking big projects into smaller ones, hence the need for subteams within Kelpie. “This allows for people to focus on their particular tasks and encourages a multidisciplinary approach to engineering, which we strongly value,” said Primera.

Notably, the competition requires that they structure themselves like a company, and in all briefings, it refers to the team as “the company.”

Think of the team like a start-up company. “When it is first formed, its more permanent members must occupy a jack-of-all-trades type of role. When the company’s goals become more rigid, [its] members’ roles must become more specialized. After our first competition, we realized the importance of specialization and dividing the team into more organized subteams,” added Jarkas.

How to build a robot for dummies?

Once you’ve organized yourselves and delegated roles, the next step is ideally building, no? Wrong. There tend to be a lot of conversations around the design table that need to happen next. Moving forward, engineering teams will work separately on individual parts, and then come together later to really build out the project — this is all standard in terms of project design and implementation.

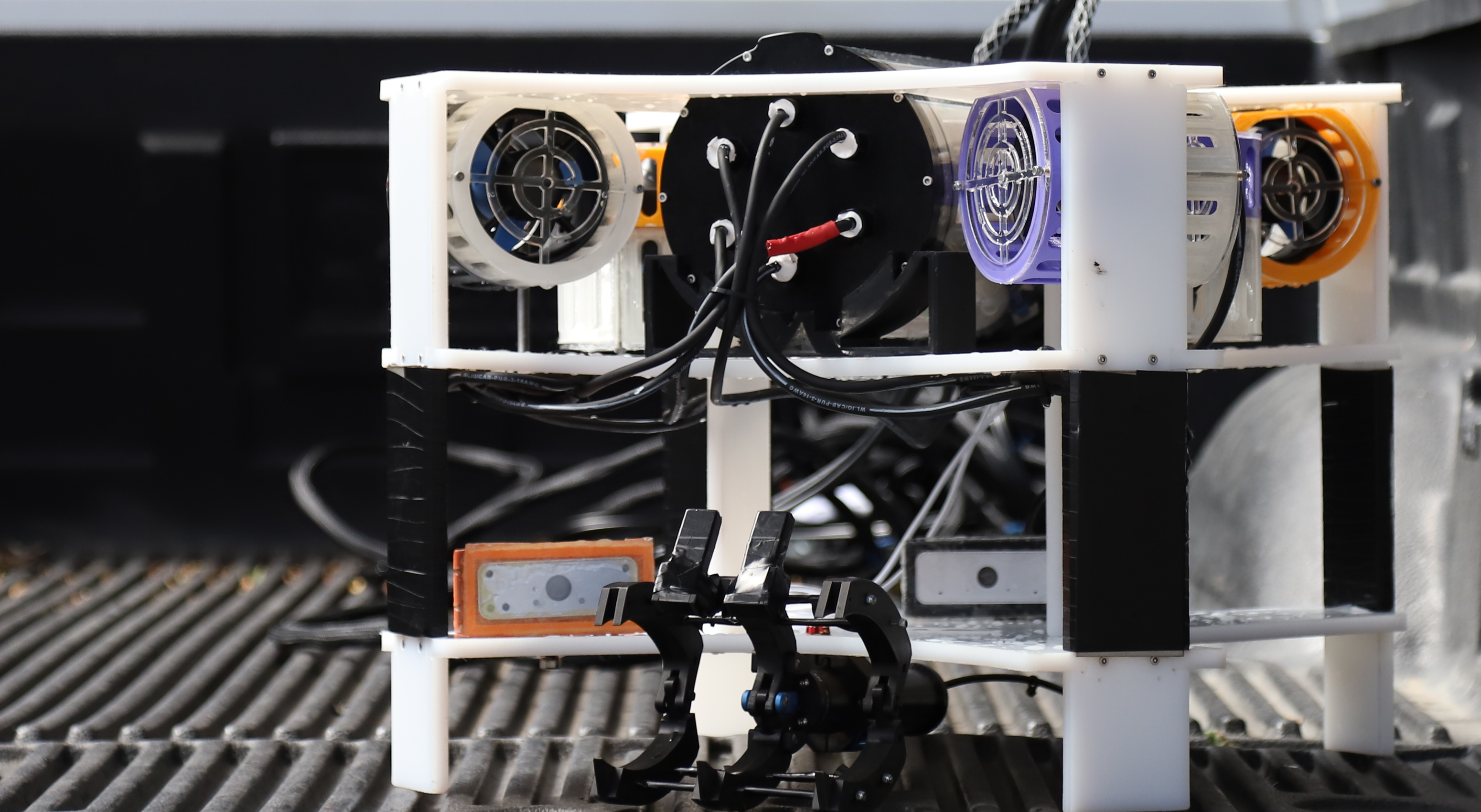

What sets underwater robotics apart from terrestrial robotics is the need for waterproofing and buoyancy. As Jarkas put it, “this opens a whole new world of constraints. The first being electronics which don’t particularly enjoy being wet, which unfortunately, have been proven by kelpie team members by the use of the scientific method.”

“We need to ensure that all the parts are waterproof and it can stay dry and can still function. The enclosure should also be able to withstand the pressure of water,” added Dompaul.

The second is wireless communication which Jarkas explained is much more complex over two different mediums (air and water). This is because radio waves attenuate, reflect, refract, and do a lot of other black magic stuff that exponentially increases the complexity of our system design (thanks electromagnetics).

He continued, “a third constraint would be colour, since wavelengths are distorted the deeper you go. This means that any task requiring any kind of colour accuracy is instantly more complicated. In short, controls, communication, navigation, or simply just being submerged in water, adds a lot of extra complexity to the design process.”

A word of advice for anyone looking to pursue engineering would be to accept challenges as they come, and in Kelpie’s case, “part shortages and supply line uncertainties as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic have been a regular issue for our team, and have led to some pretty tight timelines,” explained Primera.

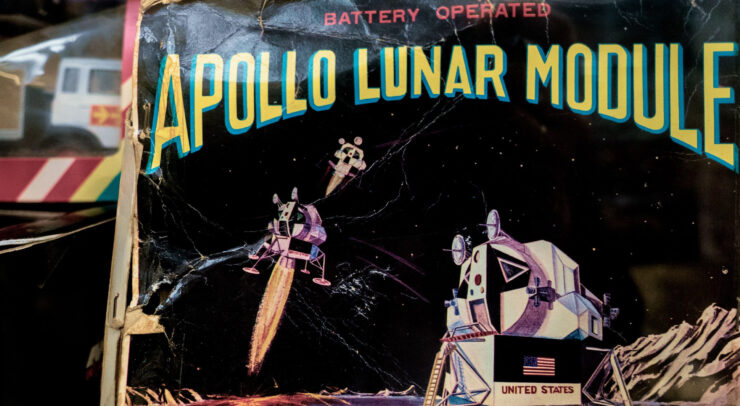

MATE ROV

According to Primera, “the MATE ROV International Competition is an underwater robotics competition where teams from all over the world compete in making a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) that can accomplish tasks meant to simulate real-world tasks.”

In previous years the tasks have been simulated maintenance of mechanical and electrical systems through stand-in parts, environmental assessments of mock plants and animals, and visual identification tasks.

Last year, the team struggled with “computer vision and autonomous movement tasks, as they require a lot of intricate sensors and camera systems to make sure we’re able to accomplish those,” he added.

In terms of changes for the upcoming 2023 competition, the team is working on redesigning the entire assembly of their ROV and more accurate stabilization and control systems. If you’re looking to get involved but aren’t sure, Dompaul says, “I wouldn’t say it’s exclusively for engineering students. We have a large and knowledgeable team that can help you get yourself sorted, get your tasks done, and lots of team collaboration!”

For more information about Kelpie Robotics, visit their website here.